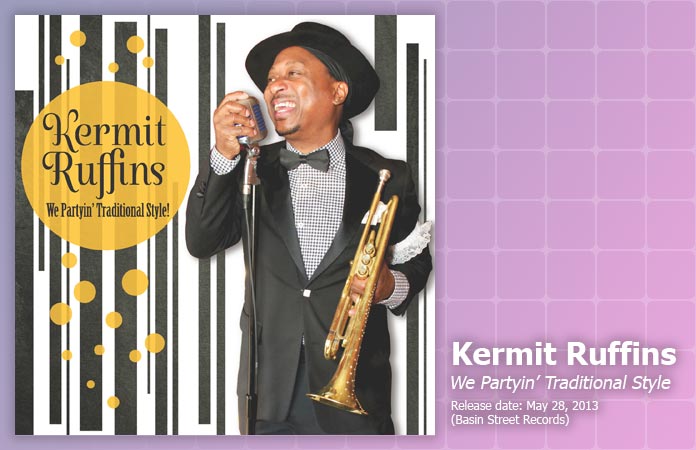

Music Review: Kermit Ruffins, We Partyin’ Traditional Style

Published on May 14th, 2013 in: Current Faves, Music, Music Reviews, New Music Tuesday |

Kermit Ruffins co-founded The Rebirth Brass Band in high school. The Rebirth Brass Band revitalized the brass band community in New Orleans, and their success rejuvenated New Orleans’s Second Line culture. Kermit Ruffins is a great ambassador for that aspect of New Orleans. His extraordinarily distinctive, raspy voice paired with his virtuoso trumpet playing gives the casual listener a glimpse into the broad spectrum of New Orleans music.

His newest record We Partyin’ Traditional Style is like a time capsule, taking 20th-century classics and skewing them his own personal way and in the process, making an incredibly fun record. Partyin’ in the title? Not a coincidence.

Music Review: Big Black Delta, Big Black Delta

Published on April 30th, 2013 in: Current Faves, Music, Music Reviews, New Music Tuesday, Reviews |

The claim that music with keyboards and synthesizers isn’t “real music” or is just crap has gone on long past its sell-by date. It was tired in the ’80s; now it’s just embarrassing. If music makes you feel something on a gut level—or hell, if it just makes you want to hit the dance floor—then who cares if it’s got synths, keyboards, or a didgeridoo?

The anti-keyboard bridge would probably break out the torches and pitchforks for Big Black Delta. Jonathan Bates has taken Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound to its most synthesized, processed extreme. It’s not just that Big Black Delta’s music features a preponderance of electronic sounds, it’s that the sounds include mountains, oceans, and skies.

Music Review: The Chapin Sisters, A Date With The Everly Brothers

Published on April 23rd, 2013 in: Current Faves, Feminism, Music, Music Reviews, New Music Tuesday, Reviews |

Like The Everly Brothers, The Chapin Sisters come from a musical family. Their father is Grammy-award-winning musician Tom Chapin; their uncle was folk singer and humanitarian Harry Chapin. This pedigree shows in their most recent release, A Date With The Everly Brothers, an album of 14 cover songs by the beloved duo.

A Date With The Everly Brothers focuses on the songs released by the siblings between 1957 and 1961, the most commercially successful period in their career. About half of the songs are Everly originals; most of the rest are Felice and Boudleaux Bryant compositions from the brothers’ tenure on Cadence Records in the late ’50s.

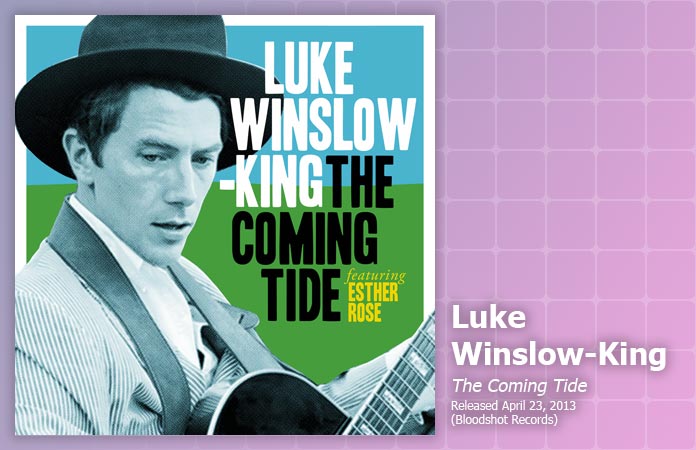

Music Review: Luke Winslow-King, The Coming Tide

Published on April 23rd, 2013 in: Current Faves, Music, Music Reviews, New Music Tuesday, Reviews |

I once saw Luke Winslow-King perform a miracle. He was opening for Jack White, which is, of course, miraculous in and of itself, and Jack White’s audience was less than receptive to this man in a seersucker suit with a guitar, a woman playing a washboard, and a fellow with a standup bass. The most amazing thing was watching the audience’s attitude change. By the third song in his set, Luke Winslow-King had made fans. His performance was engaging, wickedly tuneful, and pretty much brilliant. The interplay between him and washboard player/backup singer Esther Rose was charming. By the time his set was over, the merch table was flooded with people buying his CD.

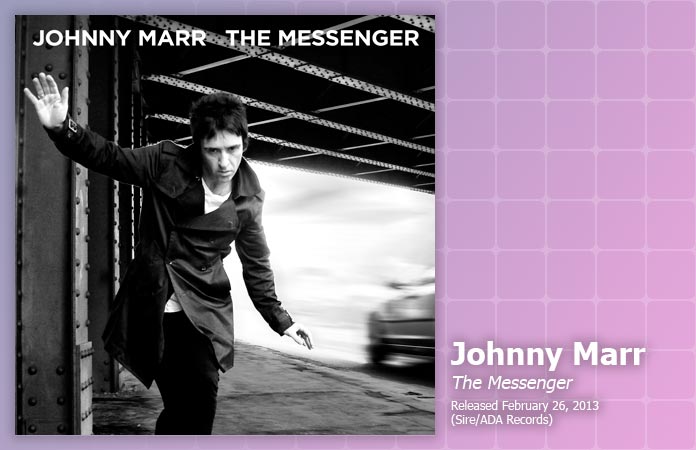

Music Review: Johnny Marr, The Messenger

Published on April 2nd, 2013 in: Music, Music Reviews, New Music Tuesday, Reviews |By Cait Brennan

“Hear me, the wonder of it,” Johnny Marr sings on “The Right Thing Right,” the opening track of his new solo album The Messenger. Marr essentially invented ’80s Britpop with The Smiths, a band whose hallmarks featured Marr’s blazing melodic runs and (oh god let’s just get it over with) jangling guitars, serving as the perfect counterpoint to those literate, mannered, melancholic lyrics from an obscure vocalist whose name time has sadly forgotten.

In the intervening years, as The Smiths’ influence has grown to legend, countless guitarists have reproduced that iconic sound with near-religious devotion. Everybody, it seems, but Marr himself, who often seemingly took pains to play like somebody, anybody other than that guy on The Smiths records. While Morrissey rose to new heights as a writ-large, Nicholas Ray CinemaScope version of himself, Marr left it all behind, blazing an exhaustive, exhausting trail through new sounds and new identities that would wear out Richard Kimble.

Music Review: Gene Clark, Here Tonight: The White Light Demos

Published on April 2nd, 2013 in: Current Faves, Music, Music Reviews, New Music Tuesday, Retrovirus, Reviews |By Cait Brennan

The experience of being alive is joyous and unbearable. This crude matter we’re made of fights us every step of the way, but something deeper, something more, some beauty and energy blasting through from a source we can’t know animates us, fills us, drives us onward, and the friction, the vibration of energy that moves us, is what we call music. Where does it go, do you suppose, when we’re gone? Nobody knows, but you’ve gotta hope that when the radio breaks, still the signal shines on.

If rock and roll means anything worth caring about, it’s the need to express something real and beautiful and transcendent from the human soul. But that need can lead to soul-destroying results. There’s a fake thing called fame today, but it’s nothing like the sun that blistered down on the rock and roll bands of the 1960s. Know-nothing hambones like Mike Love get out in front and let their egos feast on the callow roar and toxic adulation of the crowd while sucking the lifeblood out of the delicate creative genius that brought them to the party, like a fat tick on a sick dog. The songwriter gets in the way? Kick ’em out of the band and keep the carnival on the road. Don’t mess with the formula, right?

Which brings us to the Byrds’ creative genius, Gene Clark. A down-to-earth, folk-influenced kid from the Midwest, he co-founded the band, and (excepting a few covers written by some stray named Robert Zimmerman) was the songwriting powerhouse behind the Byrds’ golden age. Just a few of the highlights he wrote or co-wrote: “I’ll Feel A Whole Lot Better,” “She Don’t Care About Time,” “I’m Feelin’ Higher,” “If You’re Gone,” “Here Without You,” “The World Turns All Around Her,” “Set You Free This Time,” oh, and a little number called “Eight Miles High.”

Music Review: Old Man Markley, Down Side Up

Published on March 19th, 2013 in: Current Faves, Music, Music Reviews, New Music Tuesday, Reviews |By Paul Casey

Old Man Markley’s second album, Down Side Up, is certainly more Bluegrass than Punk. The tempo is up there but the vocal approach is quite apart from, say, The Dropkick Murphys’ mixture of traditional and hard rock influences, or indeed Shane MacGowan’s Johnny Rotten sneer pushed through the balladry of Luke Kelly. While their first album Guts n’ Teeth does have some of the growl and shout and knock back pirate chant quality to it, there are more similarities with how The Decemberists or Okkervil River approach Traditional music. Even when the lyrics get colorful and the band gets fired up, the vocals remain gently emotive. Even live, they retain much of this quality. From viewing footage of their live act, it is clear that they are a tight outfit. As a delicious stew of influences, they recall the flavor of Hot Buttered Rum.

Music Review: Shooter Jennings, The Other Life

Published on March 19th, 2013 in: Current Faves, Music, Music Reviews, New Music Tuesday, Reviews |By Emily Carney

As I sit in my apartment on a quiet Sunday morning, the Tampa Bay area is still reeling from the effects of a Kenny Chesney concert. It even merited an article in our local paper, the Tampa Bay Times. While I’m glad these fans raised a bit of G-rated hell and enjoyed some country music, some of us enjoy the grittier sounds of the son of one of the canon’s finest, Shooter Jennings. On his new release The Other Life, Waylon’s son proves himself to be worthy of his dad’s crown.

Music Review: Alasdair Roberts & Friends, A Wonder Working Stone

Published on March 12th, 2013 in: Current Faves, Music, Music Reviews, New Music Tuesday, Reviews |By Hanna

A Wonder Working Stone is being hailed as Alasdair Roberts‘s best work so far. Though he can sum it up in one word per song himself, it’s not that easy to capture in a short review. This is partly because it is so varied, and partly because it’s so complex that description becomes difficult.

In a way it’s a definitive album, combining characteristic elements of Alasdair Roberts’s style with new influences, and a cast of highly skilled musicians. There is an atmosphere of creative friendship in the album, especially in the extended sequences of various songs played together.

Music Review: Girls Names, The New Life

Published on March 12th, 2013 in: Current Faves, Music, Music Reviews, New Music Tuesday, Reviews |

I’m running out of ways to describe new bands as deft reinterpreters of the legacy of post-punk music. Belfast’s Girls Names is no exception, but The New Life, their new album, is still exceptionally good.

Those who try to recreate the sound of the late ’70s/early ’80s goldmine of great music often fall victim to throwing in everything that defined the era in an attempt to be as on-the-nose as possible: synths, drum machines, hand claps, samples, gospel choirs, and horn sections. Less is more, and Girls Names know how to do a lot with a little.