Assemblog: May 10, 2013

Published on May 10th, 2013 in: Assemblog, Film Festivals, Movies, Science Fiction, Streaming, Trailers, TV |

New this week on Popshifter: Jeff starts some Metal Mayhem with Night Ranger and Mötley Crüe (more installments are coming throughout the month); Luke reviews the “brilliant” cooperative game Monaco: What’s Yours Is Mine; Brad gets transported back to childhood through Jason Lapeyre’s new film I Declare War; and I am impressed with ChristCORE, a new documentary on the Christian hardcore scene seen through the eyes of a nonbeliever.

Assemblog: April 19, 2013

Published on April 19th, 2013 in: Art, Assemblog, Film Festivals, Horror, Movies, Trailers |

New this week on Popshifter: Jeff describes how Cliff Richard is wired for sound and explains the pros the cons of hitch hiking; Julie saw The Hives and has photos to prove that they’re a “fantastic rock & roll band in the purest sense”; I praise the exquisite songwriting on IO Echo’s debut album Ministry of Love; and Chelsea mourns the loss of Scott Miller (Game Theory, Loud Family).

Canadian Music Week Film Fest Movie Review: Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me

Published on March 26th, 2013 in: Current Faves, Documentaries, Film Festivals, Movie Reviews, Movies, Music, Reviews |

When I first heard Big Star, I wondered “Why weren’t these guys huge?” like all their other fans have been wondering for the last 40-plus years. Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me answers the why, but their lack of mainstream success still boggles the mind. When Brian Wilson sang “I Just Wasn’t Made For These Times,” he could have easily been singing about Big Star.

The story of Big Star is full of both good things—talent, camaraderie, ambition—and terrible ones—bad luck, personal demons, and death. This mixture of the bitter and the sweet is a good metaphor for Big Star’s music, which fuses the two in an unforgettable aural and emotional experience. This is what drew fans and critics to the band and what continues to characterize their legacy.

Canadian Music Week Film Fest Review: Bad Brains: A Band In DC

Published on March 23rd, 2013 in: Current Faves, Documentaries, Film Festivals, Movie Reviews, Movies, Music, Reviews |

When it comes to bands like Bad Brains, genre becomes meaningless. Influenced by such disparate artists as Chick Corea, The Sex Pistols, The Damned, The Ramones, and Bob Marley, they combined a variety of musical styles into their own unique sound, going on to influence dozens of other musicians (Dave Grohl, The Beastie Boys, Cro-Mags, Red Hot Chili Peppers, to name but a few) in the process.

Bad Brains: A Band in DC, directed by Ben Logan and Mandy Stein, is not an exhaustive account of the history of Bad Brains; that would be impossible, although it would make for an extremely entertaining TV series. When watching the film, you’re not only left with the distinct impression that there are many more stories to be told, but also that you can’t wait to dig into the band’s discography, which includes nine studio albums, a couple dozen singles, a handful of live albums, and appearances on various compilations.

Assemblog: March 22, 2013

Published on March 22nd, 2013 in: Assemblog, Copyright/Piracy, Film Festivals, Horror, Legal Issues, Movies, Trailers, True Crime |

Under The Bed

New this week on Popshifter: LabSplice says Brad Anderson’s new movie The Call is “guided by a very sure hand”; Emily thinks Shooter Jennings is worthy of his dad’s crown on The Other Life; Paul recommends Old Man Markley’s Down Side Up; I unabashedly gush about Suede’s Bloodsports, categorize the movie Deadfall as a “gritty, rewarding genre exercise,” admire the fashion sensibilities of Redd Kross in their new video for “Uglier,” and review four films from Canadian Music Week Film Fest 13: Ain’t In It For My Health, The History of Future Folk, The Last Pogo Jumps Again, and Apocalypse: A Bill Callahan Tour Film.

Please note: there will be no Assemblogs for the next three weeks. I’ll just be providing round ups of that week’s articles. The Assemblog will be back in full effect on April 19.

I’m sad to report that our ongoing column “TV Is Dead, Long Live TV” is on hiatus. If you’re interested in picking up the coverage of the transformation of television from linear to its currently shifting model, please drop me a line at editor@popshifter.com.

Canadian Music Week Film Fest Review: Apocalypse: A Bill Callahan Tour Film

Published on March 22nd, 2013 in: Film Festivals, Movie Reviews, Movies, Music, Reviews |

I started watching Apocalypse: A Bill Callahan Tour Film knowing nothing of Bill Callahan. Callahan has been writing, performing, and recording music for almost 25 years, originally under the name Smog, and then with the release of 2007’s Woke on a Whaleheart, under his own name. Apocalypse chronicles Callahan’s US tour in 2011 to support the album of the same name.

Canadian Music Week Film Fest Review: The Last Pogo Jumps Again

Published on March 22nd, 2013 in: Canadian Content, Current Faves, Documentaries, Film Festivals, Movie Reviews, Movies, Music, Reviews |

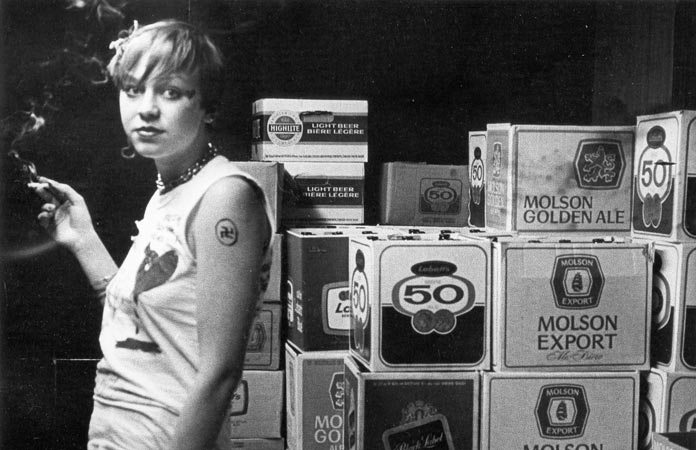

Photo © Gail Byrek

For documentaries that chronicle a certain scene, be it music, theater, film, or another art form, the question many might ask is why? Is the documentary supposed to shed light on a misunderstood or little-known series of events? Is the documentary trying to cast the people and events in a flattering or unflattering light? Or, as some might speculate, is the documentary just a forum for those involved to pat themselves on the back and say, “I was there”? For The Last Pogo Jumps Again, the answer to all of these questions is yes, but it’s a qualified assent.

Canadian Music Week Film Fest Review: The History of Future Folk

Published on March 20th, 2013 in: Current Faves, Film Festivals, Movie Reviews, Movies, Music, Reviews |

Despite being set in modern times, The History of Future Folk feels like a movie from 30 years ago. Recall, if you will, when niches weren’t quite so niche-y, and a movie could include comedy, drama, romance, science fiction, and/or suspense without being a rom com, a dramedy, or a sci-mance (I just made that last one up).

It’s a shame that self-congratulatory cynicism has also infected the cinematic realm, particularly when it comes to criticism or just people blabbing on the Internet. The History of Future Folk is a movie that is sweet, charming, funny, and exciting, but not corny or cloying. You could take your mom to see it and neither of you would be embarrassed. It’s genuinely warmhearted and enjoyable, which is a rarity these days.

Canadian Music Week Film Fest Review: AIN’T IN IT FOR MY HEALTH: A FILM ABOUT LEVON HELM

Published on March 18th, 2013 in: Film Festivals, Movie Reviews, Movies, Music, Reviews |

If you are a fan of The Band, then you already know that drugs and money are a bad combination. Ain’t In It For My Health doesn’t dwell on the troubled legacy of the group, but it doesn’t shy away from it, either. However, this is a film about survival, and the exceptional life of Levon Helm, drummer, singer, songwriter, father, friend, and legend.

Filmmaker Jacob Hatley shot the footage for Ain’t In It For My Health throughout 2007 and 2008. It encompasses Helm’s 2008 Grammy nomination for Dirt Farmer, the recording of Electric Dirt, his contributions to The Lost Notebooks of Hank Williams, and the birth of his grandchild and namesake, Lavon. (Helm was christened as Lavon, but became known as Levon when no one in Ronnie Hawkins’ band could correctly pronounce his name.)

Canadian Music Week Film Fest 13: An Overview

Published on March 15th, 2013 in: Canadian Content, Film Festivals, Movies, Upcoming Events |

You’ve probably heard of Canadian Music Week, but did you know that films are part of the festivities? Much like South by Southwest and North by Northeast, where there is music, there are films. If you have music, films will come (or something like that).

This year marks the sixth annual CMW Film Fest (as it’s called ’round these parts). It takes place over three days, from March 21 – 23. Conveniently, all movies will be screened at the TIFF Bell Lightbox on King Street West in Toronto.

I’ll be reviewing every film in the festival over the next week or so, but in the meantime, here’s some short previews of what to expect.