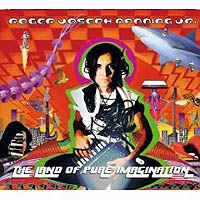

Speaking The Language Of Pop: An Interview with Roger Joseph Manning, Jr.

Published on July 30th, 2008 in: Current Faves, Interviews, Issues, Music |Interviewed by Less Lee Moore

Even if you have never heard of Roger Joseph Manning, Jr., you’ve probably heard him. You might know him best from Jellyfish, Imperial Drag, Malibu, Moog Cookbook, or TV Eyes. But he’s worked with dozens of other bands and musicians: from Air, to Beck, to Cheap Trick, to pretty much every other letter in the alphabet. Except Q and X (I checked).

He’s a tremendously talented musician, singer, and songwriter and an incredibly down-to-earth and intelligent guy. I feel lucky that I got to interview him; I could have easily talked to him for hours. And here’s why.

Popshifter: I saw Jellyfish back in 1990 in the Pub, which was in the basement of the UCSB University Center. That is my first memory of hearing about Jellyfish and your music. When you think of Jellyfish, is there one moment that you think of or a specific memory?

Roger Manning: Wow, well, not one in particular. The brain has a clever way of protecting the psyche. Every band has its ups and downs. And as many downs as there were, of course those that eventually led to the band’s break up, I look back and I can only remember the fun, fond memories for the most part.

It was so long ago now that all the tours have kind of melted into one. There were lots of great memories, especially if we were opening for a band like the Black Crowes who wasn’t our audience per se, and we had the task and challenge of winning over a bunch of people who hadn’t necessarily heard the record. There was a great joy in kind of banding together and really trying to put on a show for that audience. You’d put your differences aside and see if you could convert the “unpopped.” (laughs) And bring them some sing-along music that they might be too embarrassed to play in their hot rods in front of all their masculine friends.

Popshifter: (laughs)

Roger Manning: So all of that stuff and all the laughs in between, even if it was during hardships. The traveling, especially if you don’t have much tour support, was always really difficult. I always flash back on people making each other laugh. It was an incredible experience even though it almost killed me emotionally and physically—I was sick quite a lot—but I wouldn’t trade it. It was a really unique opportunity that I know only a small percentage of musicians ever get to experience. No regrets.

Popshifter: I always forget that Steve McDonald [from Redd Kross] played a lot of instruments on the first album Bellybutton.

Roger Manning: Yeah, we didn’t have an official bass player so he was one of our friends that we called in and he played bass on two tracks.

Popshifter: How did you meet him? Were you a fan of Redd Kross at that point?

Roger Manning: Yeah, we’d been fans for years. The running joke was that in finding the other musicians we wanted to round out the group, Andy [Sturmer] and I would reference Redd Kross. “We want a guitar player like Robert [Hecker].” Or “We want a bass player like Steve.” I had spent a lot of time in L.A. going to college and working in different bands even though I was from the san Francisco Bay Area, so I knew some people that actually knew them. I was actually in a band, very briefly, that was being produced by Robert. Now, we never did a record, but a lot of the same people in the South Bay music scene knew them, so it was only a matter of time before I got a message to them. This girl we knew knew Steve and she invited him out for pizza and introduced Andy to him and two weeks later, he agreed to come in and play bass. I mean, he hadn’t heard anything and he really didn’t know our sound at all. He was a real trooper and I can’t thank him enough for taking the risk. He didn’t know what he was getting into.

Popshifter: The thing is, around that time, the late ’80s, they were doing the Third Eye album, so weirdly there was kind of a similarity with the bubblegum pop and 60s/70s sound of that album and you guys.

Roger Manning: I can remember being in San Francisco going to see the band The Wonder Stuff. The band that opened was a band I’d never heard of from Seattle called The Posies. This was also in 1988, 1989. I totally fell in love with them. I didn’t know a damn thing about them, and I kept my eye on them. And then of course, you get in your own world but in the fall of 1990, as you remember, [The Posies’] Dear 23 [album], Third Eye, and Bellybutton all came out within weeks of each other.

It was no mystery to me—it was weird as hell—but it was no mystery to me. It was very convenient for the press to lump us all together. Obviously we did have a lot of the same influences, but we were pretty different-sounding. You could probably say that Redd Kross and Jellyfish were more similar-sounding; the Posies definitely have their own brand. There was such joy to play those few shows where all three of us were on the same bill.

I would’ve loved to tour the country with those guys but all three of us had already booked separate tours, so it was impossible.

Popshifter: What the media could have connected the three of you with was Bill Bartell.

Roger Manning: (laughs)

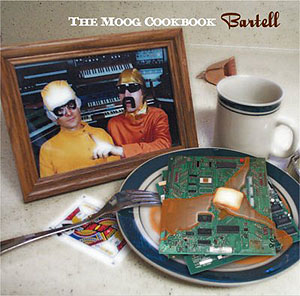

Popshifter: I read an interview with you where you talked about the name of the [last] Moog Cookbook album. You said, “If you know Bill, it’s hard for people to hear his name without starting to laugh,” which is really true. At what point did you encounter him in this band genesis?

Roger Manning: As you can imagine, shortly after opening the relationship with Redd Kross, I mean, he’s a fifth Redd Kross member—

Popshifter: (laughing) Has he actually said that? Because it sounds like something he would say.

Roger Manning: Oh, I’m sure he has. But he’s never said it to me. It was only a matter of time. He makes himself present. He came to a lot of shows that we did with [Redd Kross]. Later, when I would go on to write with Jeff and Steve for Phaseshifter, he was part of that, albeit peripherally. I mean, I could go on and on. I just saw him at a mutual friend’s party after not seeing him for about a year. He’s alive and kicking.

Popshifter: Another connection that you have is doing some music for a Joel Hodgson TV project? How did that come about?

Roger Manning: You know, I actually ran into Joel and his brother [Jim] I think at a Farmer’s Market buying groceries.

Popshifter: Were you a Mystery Science Theater 3000 fan at that point?

Roger Manning: Huge. MST3K is basically how I got through touring.

Popshifter: That’s so funny because that is how I got through college.

Roger Manning: I would tape everything if I didn’t have time to watch it and just take it on the road. It would take my mind off excruciating boredom.

They recognized me as being a member of Jellyfish because I think Jim approached me. Obviously I would’ve recognized Joel, but he was on the other side of the market. Jim introduced himself, brought [Joel] over and started talking about it.

I said, “Well, we’d love to try some music for this project.” There was no money involved because they were doing it all out of their pocket, trying to sell a pilot, basically. My partner in Moog Cookbook [Brian Kehew] loved the idea. It was basically a song they had sketched up and we kinda turned it into a synthesizer arrangement.

Popshifter: Was this the TV Wheel show?

Roger Manning: It was an incarnation that had similarities to, but was set up very differently than, the TV Wheel. You might have seen the thing that they finished, where we helped with the music, and go, “Oh, I can see how this evolved.” I never saw any finished product and I don’t even know to what stage it got completed.

Popshifter: We’ve just talked about some of them, but you’ve worked with a lot of people. On your website there is a long list of them. Is there anyone that you haven’t worked with that is kind of a dream for you?

Roger Manning: Absolutely. It’s really interesting: I have worked with so many cool people and several of them have been childhood heroes of mine. I just finished another Morrissey record and being asked to do that is just still surreal to me.

Two people come to mind, and they’re pretty damn obvious: Andy Partridge from XTC and Elvis Costello. The thing is, with those guys, though? They’re so. . . one-man-band. They can do so many things on their own and they have such great ideas. And I’ve always held them in such high esteem, I think that even with all my experience, I’d probably be a bumbling, nervous, teenage schoolgirl.

Popshifter: (laughs)

Roger Manning: I’d probably embarrass myself. You know what I mean? It wouldn’t be as cool or fun or fantastical as my brain could imagine.

Popshifter: It’s interesting you brought up those two being able to do stuff on their own. I’m also a fan of Jason Falkner [who was in Jellyfish for the first album] and I’ve read a lot of interviews with him where he’s said that sometimes he finds it easier to do stuff by himself because it’s hard for him to translate that into working with other people. Do you ever feel like that?

Roger Manning: Absolutely. It’s very frustrating. I have to be careful when I work with others. You kind of tie one hand behind your back. You’re so used to working on your own and having your own way, you don’t have to exercise a lot of patience.

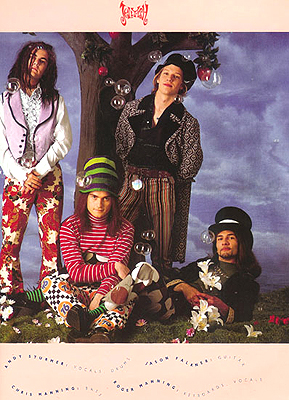

TV Eyes (L – R):

Jason Falkner, Brian Reitzell,

Roger Manning

Everybody has a different way of getting to the finish line. Everybody arrives at that finish line in a great way, but how they get there is something we can’t judge, and I’ve learned that you kind of just have to let the process take care of itself. You’ve got to be patient to do that. I totally understand what Jason was saying; you don’t want to be patient. You just want to get in there and do it.

So that’s why all of the different sessions I do are great practice for that. It was very sad to voluntarily walk off the Beck tour in 2001. I basically wasn’t making enough records. I mean, I was working on his records (laughs), but that was about it. I wanted to play on all kinds of records, including my own, but that wasn’t going to happen from a hotel room in Omaha, Nebraska.

As sad as that was, I’m really happy I did it. Because I’ve had so many incredible experiences since then with such a wide variety of music-makers.

Popshifter: Obviously the projects you’ve done with Jason Falkner and Brian Reitzell [formerly of Redd Kross] have worked out really well. There is the Logan’s Sanctuary thing and TV Eyes. I know they’re both incredibly busy but have you talked about getting together on any other projects?

Roger Manning: Part of that conversation was that we were all so busy and happy doing our own individual things—Brian is incredibly busy doing film scores [Lost in Translation, etc.]—that we knew that we had definitely tried our best to get the TV Eyes thing off the ground and we’d all spent so much time and it just didn’t happen at the level we wanted it to. So we were like, at least we got to do the one record and get it out in Japan. If someone wants to put it out in the States, that’s fine, too. But there is an EP out now which has three previously-unreleased songs and four remixes.

I can’t believe it, but it was eight years ago this summer that we… well, the idea came from Brian Reitzell in 1999 when we were working on the second Air record [10,000 Hz. Legend]. It was the summer of 2000 that we all got together at Jason’s apartment and started swapping song ideas that became the [TV Eyes] album.

There was a period when we were working on it every day and the live show, which I’m very happy to say, I’m going to be releasing on DVD from my site pretty soon—

Popshifter: That’s great. I really wanted to see those shows at the time.

Roger Manning: We only did three [live] shows and they were mostly for the purpose of inviting record company people to check it out. Now, we knew there was going to be a huge live video component to the show, but it was going to be extra-involved in that all the video was going to be synced to the music. It was all going to be locked rhythmically. And that is much easier said than done.

Especially Jason and I spent a good four months in front of the computer, chopping up all kinds of video scraps to make background videos that you could sync live. And the DVD will ideally showcase that. So people like yourself who couldn’t be in attendance will get the next-best-thing to what that was all about.

Popshifter: One thing [of yours] I really like, which I show a lot of people, and which universally gets a lot of positive reaction is the YouTube video with Ross Angeles.

Roger Manning: Yeah, that’s good stuff.

Popshifter: It’s so hysterical. Now, who is he and how did that video come about?

Ross Angeles

Roger Manning: Ross is a very interesting family tree member, so to speak, so you’ll get a kick out of this, knowing a lot of the history of different bands.

When I first moved down from the San Francisco Bay Area, before I moved into L.A. proper, I lived in Ojai, which is close to Santa Barbara.

Popshifter: Yeah, Ojai’s pretty small!

Roger Manning: Yeah, it’s very small and that’s where my girlfriend and I lived for three years. It was right after Jellyfish had broken up and I was basically waiting for Eric Dover to get off the road with Slash [in Slash’s Snakepit] so we could finish the Imperial Drag record. I was so depressed over Jellyfish breaking up, I was so anxious and frustrated with Eric disappearing when we were in the middle of Imperial Drag, that I kind of went berserk and started buying and selling a lot of old music gear. Now the good part about that was that I found a lot of good equipment that I could make a lot of cool, crazy sounds with.

The bad part was that, that’s all I did. I didn’t write songs, I didn’t jam in bands, I didn’t go to shows. I just became a gear addict. It was during those travels that I met Ross. He was interested in buying a keyboard I was selling in the paper.

And he came over and I was like, “Who is this freak? And why do I get along with him so well? He’s really cool!”

Popshifter: (laughs)

Roger Manning: He had a really great sense of humor and we stayed in touch, even though it was just that one meeting. He would invite me to projects he was working on with this band he was starting at the time and we just stayed in touch over the years.

Well, cut to two and half, three years later and we were still in touch about weird gear and eccentric records—we were really into Italian film soundtracks and stuff—it came up that he had been good friends with Beck before Beck was who we all knew Beck to be. (laughs)

Popshifter: Right, when he was sleeping on the street and recording songs into his tape recorder.

Roger Manning: Yeah. For a while, Beck was living at Ross’s house and they were in a band briefly together. Before Beck went solo he was in a band called Loser. And all these people to show up later in his life were part of that group or “scene,” if you will.

That scene was extra weird because it had a lot of child actors in it. Like Ross himself, was a child actor in the 70s and early 80s. The most famous thing he’s known for is being the little boy in the first Airplane! movie. He sits in the cockpit and gets tutored on how to fly the plane.

Popshifter: (laughing) Oh, is that the one with “have you ever watched any gladiator movies?” That kid?

Roger Manning: Exactly.

Popshifter: (cracks up)

Roger Manning: That’s Ross Harris.

Popshifter: That’s hysterical! I never knew that.

Roger Manning: He lost interest in that as a teenager; he was more into music and video production. Basically Ross had a huge role in me getting into Beck’s band. We had a few mutual acquaintances. Beck knew Moog Cookbook, but not Jellyfish or Imperial Drag.

When [Beck] had a falling out with his keyboard player on the Odelay tour, I asked Ross, “If there is any way you can put a good word in for me, I would really appreciate it.” I know he did and I think that had a lot to do with me getting called to audition.

We just stayed in touch and he did the artwork for my solo record [Solid State Warrior]. I wish I could see him more, but I only see him every three to four months. (laughs)

Popshifter: You showed quite a few of your keyboards in that video and I don’t remember if you actually had a count, but you obviously had to for insurance purposes. How many keyboards proper do you have?

Roger Manning: It got stupid. I’ve been selling a lot of stuff these past few years. But before I started selling stuff, it was somewhere around 150 pieces.

Popshifter: Oh my god.

Roger Manning: Now it’s about half that. Which is still ridiculous.

Popshifter: (laughs)

Roger Manning: I’ve got 60 to 70 keyboards, which is still absurd but I have been selling a lot of equipment.

Popshifter: But these are things you can play.

Roger Manning: Yeah, I use a lot of them.

Popshifter: I mean, having that many pairs of shoes might be a little. . .

Roger Manning: (laughs)

Popshifter: . . . although there are people who do!

Roger Manning: Oh god, yes.

Popshifter: Do you play video games at all? Have you heard about this KORG DS-10, which is a KORG program coming out for the Nintendo DS?

Roger Manning: I have not. The video game bug bit the kids right after me. Both of my younger brothers, and Ross, Beck, and those guys, that’s their whole world, too. I was into Centipede, for like two weeks. I think it was the one game I could actually improve on.

Popshifter: (laughing) That was the only one I could ever succeed at, either!

Roger Manning: Everything else just drove me insane. I was like, “What is the point?” I wanted to figure out like, how to write songs and how to ask girls out on dates without fainting.

Popshifter: (laughs)

Roger Manning: Playing video games was not helping either of those.

Popshifter: (laughing) No, it probably would have made it worse! You’ve talked about Ross and how pretty much everyone involved with Beck and his band were really funny. You’ve said several times that you think humor is important, particularly in the face of more negative or adversarial situations. Is that something you explore better with your solo projects or do you feel like you are able to bring that to your collaborations with other people?

Roger Manning: As far as humor goes, I just think it’s a crucial element to being a balanced human being, and therefore, to being a balanced creator or artist. To answer your question, more specifically, I don’t feel for the most part that a lot of people I end up collaborating with understand the value of a healthy relationship with humor and not taking themselves too seriously during the creative process.

Nor do I feel the public has been educated to appreciate that. In other words, I think a lot of people think, “Oh I can’t take this band seriously.” The public has been trained in having one-dimensional creative figures.

For example, Radiohead is a respected band around the world. If they injected even two percent more humor into what they do, their fans would be devastated. Because they’d be like (adopts dorky offended tone), “What? What? Now are they a joke band? If they don’t take themselves seriously, how am I going to take them seriously?”

Popshifter: That’s a really good observation.

The Cure

Roger Manning: I’ve seen it proven time and time again. It takes a person who is kind of in touch with themselves and understands that laughing is as important as crying, and that’s as important as celebrating and being joyful. Everybody is going to latch onto groups at different times.

If you’re going through a very difficult teenage or adolescent phase, and you’re moping around and you’re depressed and suicidal, and you can’t figure out the world and you’re overwhelmed, naturally you’re going to be drawn to that in your art. So you’re going to be drawn to groups that are mopey and introspective and mourning the world, as you are. Because you identify with that. I understand all that.

Fortunately for me, and the people whose company I enjoy the most, it was always about experiencing all that stuff. And yeah, the sucky parts suck, but embracing them is part of the process. I think that the artist can ultimately suffer in what they have to offer if they’re not aware of that.

The Cure is a really great example. They were a band who, if you didn’t examine them in depth, you would think they were just another Goth band. Robert Smith always laced what they did with a kind of tongue-in-cheek thing. Siouxsie and the Banshees did too, but The Cure… you kind of have to be really not paying attention as a Goth fan to see that The Cure never took themselves 100 percent seriously. Especially as they got more popular: they kind of laughed at the whole damn thing. I really related to that. I thought that band was brilliant—I still do—and that they were one of the most brilliant bands in rock history. I saw that they had a very healthy balance, with well-thought-out doses of humor injected into their art.

Roger Manning: That’s who I was, so it was very natural for me to bring that to Jellyfish and all the bands I’ve been involved with. It wasn’t until I finally hooked up with the Beck camp that I realized, “Oh, here are some like minds.” Beck takes his work very seriously and he does all kinds of styles. He has what I consider a very healthy balance, artistically. Humor was not the only part of that. Some fans wanted him to just be a joke, white hip hop guy, but that was just a part of what he offered.

I think he related to that in me. The honoring or paying homage to this style of music, but maybe taking the piss out of or parodying that type of music. But with a healthy respect for all of it.

That’s what the Beastie Boys were about, even some of my favorite bands which directly inspired Jellyfish: Cheap Trick, Sweet, and Redd Kross. That was understood.

I’ll tell you, it’s been very hard. An A & R guy from a record company told [Jellyfish] something that crushed me, but to this day I think he had a valid point. That’s why it’s very delicate and you have to be very self-aware. You have to have a real understanding of who your audience is and what you want to say to them.

This A & R man said that this is why [Jellyfish] had success, but ultimately why [we] didn’t have enough success. “Jellyfish was like taking a painting of the Mona Lisa and all the respect, and adoration, and high art that comes with that. And then walking up to it and painting a big clown nose on it.”

Now that’s a very truthful and poignant commentary. What he was essentially saying was, here you guys are presenting some incredibly elevated, thought-out, provoking music, and a lot of people can’t get past that because of your silly videos and silly outfits. And your kind of jokester attitude on stage. Because if you guys don’t take yourselves seriously, how are the fans going to take you seriously?

And that’s how we get back to what I said before. Your average fan has been conditioned, because music is reduced to a product, like going to the store and buying your vegetable oil. Here’s the band I listen to when I want to party, here’s the band I listen to when I want to get drunk and dance, here’s the band I listen to when I’m in my room and the door’s closed and I hate the world. . . you know what I mean?

Popshifter: Yeah.

Roger Manning: What slot does Jellyfish fit into? Because if they don’t, I’m not going to take my $16 and throw down for the CD. I’m going to take my $16 and go buy something where I know what I’m getting. And with Jellyfish, I’m confused.

Popshifter: Speaking of Morrissey, I think he’s another person who is really unfairly tagged with being mopey and gloomy, and he’s hilarious. His lyrics are hilarious.

Roger Manning: Absolutely.

Popshifter: He’s a big fan of Sparks and I think they’re another band who people get so confused by. They get the humor but sometimes they think it’s too goofy. So many articles I’ve read are like, “Sparks are really good, but I can’t stand that scary guy.”

Roger Manning: (laughs)

Popshifter: I think it’s telling that Morrissey and Sparks are such mutual fans of each other. They’re so similar in their senses of humor.

Roger Manning: You nailed it. When Morrissey found out to what degree I was a Sparks fan, it was like, “Okay, that’s it. Now Roger’s part of the club.”

Popshifter: I didn’t know that you were a big Sparks fan.

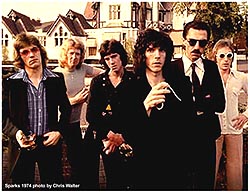

Sparks 1974 © Chris Walter

Roger Manning: They are—and I can’t believe I didn’t mention them sooner—the quintessential balance between great rock and roll, and songwriting, and entertainment. . . and having a healthy dose of wit and humor. It never sabotages the music to me and in fact, it’s a crucial component.

Popshifter: You’re really known for your keyboard and piano work. What do you think of the different styles of people like Ben Folds or someone like Quintron?

Roger Manning: I’m just happy to see keyboards and that techie side. I love that character as much as I do the Rick Nielsen, Brian May, Jimi Hendrix guitar-hero kind of guy. If Ben Folds is a modern Elton John for people, that’s great. I’m not familiar with Quintron, though.

Popshifter: Oh, you should check him out. He reminds me a little bit of Beck in that he has a lot of soul influences. The Drum Buddy is his invention, and it’s a light-activated instrument that he plays with his keyboards. He did this great album with the Oblivians from Memphis. He’s very outside of the mainstream and does things his own way. My husband always wonders if you would collaborate with him because he thinks it would be really cool.

Roger Manning: There are so many things that. . . I would still love to be out touring. Basically you just have to clone me. I have to prioritize. It’s kinda sad, but that’s just the way it is.

Popshifter: (laughing) I understand. There are so many things I want to do but there just aren’t enough hours in the day. In terms of film soundtracks or things like the Logan’s Sanctuary project, which isn’t for a real film, what are your favorite film soundtracks?

Roger Manning: Oh, I would have to give that some thought! (laughs) There are quite a few good ones, especially in the 70s where there were guys scoring entire films with just their arsenal of keyboards. I like that era. Those guys are my (laughs) comrades.

There are guys that are masters that I respect. One of the best ones ever is the Planet of the Apes soundtrack by Jerry Goldsmith. And that has no synthesizers.

Now, although there is not a lot of original music, the Wendy Carlos soundtrack for A Clockwork Orange. That’s one of the greatest examples of music and picture coming together. And the fact that all through the score, it’s all realized through very primitive synthesizers. The end result, with the very potentially offensive and aggressive imagery coming from the screen, adds up in the way that Kubrick knew how to do so well.

Popshifter: Are there particular directors that you’d like to score films for? It doesn’t have to be somebody current.

Roger Manning: The whole thing with film scoring, especially in college, I really thought I was going to be heading in that direction.

Popshifter: You went to USC, which is known for its film school.

Roger Manning: Yeah, the film school was exploding and in fact, the guys I went to parties with were all film school people. All of my roommates were. In fact, one of my longest roommates, David Goyer, wrote Batman Begins.

Popshifter: Wow, I didn’t know that!

Roger Manning: He was the guy I would go to comic book conventions with. I scored two of his student films. It was very easy to get into that headspace. And every time I’ve had to opportunity to get into it, I’ve realized that, although I respect it a lot and I look up to the people who do it and do it well, I still derive so much more pleasure from crafting pop records. That’s what I think that, the more and more I do, I get better at. I just keep wanting to practice, like, “let’s do another record.”

I just finished writing a bunch of songs with Linus of Hollywood who has been my bass player live and is a solo artist in his own right. He and I just did a bunch of songs that we want to sell to Japanese publishers for Japanese teen stars.

This was Linus’s idea. The thing about the Japanese scene, is it’s a lot more Beatle-y, so you can do stuff that comes more naturally to me then trying to sound like Britney Spears. Of course, that is an element, but you can put more sing-along type hooks and they like it more. It’s not so hip hop.

Linus brought that idea to me and I jumped at it. It’s like, okay here’s something I’ve never done and it sounds really fun and I think if I just try hard enough I can actually be okay at it. That’s something else where most of my fans won’t know about unless I tell them.

Popshifter: Would you ever consider doing fake film soundtracks? I love music that has no connection to a film but sounds like it should.

Roger Manning: I don’t know if you’re familiar with the stuff I’ve done under the moniker of Malibu. A full record came out last year in America on Expansion Team records out of New York. It’s more of a dance label

It’s my take on Kraftwerk and Giorgio Moroder through Fatboy Slim. It’s definitely me getting out and away from everything everyone knows me for, and having lots of fun. More late ’70s, early ’80s, German hard disco, keyboard-based music.

Popshifter: What are you listening to right now that is inspiring you?

Roger Manning: I used to get introduced to groups the same way everybody did, which was late night video watching.

Popshifter: (laughing) Yeah!

Roger Manning: And the occasional cool magazine or a friend hipping me to something. The fact of the matter is, those avenues just aren’t around. There may be some totally cool band happening and I know nothing about them because I’m not in those circles and I don’t do regular blogging. Frankly, I don’t have the leisure time. I’m so immersed in trying to get the next thing out to my fans to make them happy.

So once in a blue moon something will fall through the cracks and really turn me on. A friend of mine sent me a video the other day because he was trying to show me something cool the art director did in the video. And he said the song’s pretty amazing, too. And it was.

It’s this French duo, kinda like Daft Punk, but more full hard disco. They’re called Justice.

Popshifter: Oh, I heard they were amazing at Coachella!

Roger Manning: People always ask me, “What’s your favorite kind of music?” And I’m like, “I like everything.” The thing is, I only like about five percent of it. I mean, I hate disco, but there is about five percent of it that I thought was brilliant. Most New Wave was a disaster, but there are a few bands—Echo and the Bunnymen and Devo—that were great! I mean, amazing, amazing shit. If you look at my record collection, that’s what it’s like: my favorite 60s, 70s, disco, New Wave, punk, reggae, dance music. . . it goes on and on.

Herbie Hancock

I’m not saying I’ve discovered and heard everything; there are still 60s psychedelic and garage bands that I’m getting turned on to through reissues and stuff. But I like country music, bluegrass. . . I’m a huge jazz snob. I went to music school as a jazz pianist. I wanted to be Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea but it was too much fun to dress up like a girl and jump around onstage singing songs I’d written with my friends.

To this day, I love playing jazz piano but I have more fun making rock and pop for people to sing along to. If somebody says it’s retro, fine. If somebody says it reminds them of The Carpenters, great, that’s a compliment. I don’t care what the commentary is; if I’m moving people and they are singing along while they’re stuck in traffic, that’s why I’m on the planet.

Popshifter: That also relates to the question of music downloads. Obviously there are issues related to downloading. How do you think that type of technology has impacted fandom?

Roger Manning: I have no clue. All I know is that the model I grew up with—and I’m not saying it’s the right model—no longer exists. We are in the birthing pains of what will be a new, grand, and glorious way for people to listen to, exchange, and experience music. I honestly believe that.

The old model, where the major label was basically the mafia loan agent—

Popshifter: (laughing) Oh god. . .

Roger Manning: —where they basically were the bank and they gave you a loan. And for that, they collected huge interest, just like regular loans. But this afforded a small percentage of musicians to get their music heard by lots of different people. That model is completely over with, no matter how much people are trying to hang onto it. And I can’t tell you what’s it’s going to look like, but I will say this. I guarantee that the creative people, the artists themselves, the producers, art directors, video directors, everybody who is involved in the creative side of the record-making process? They will come out much more ahead, with much more control and much more freedom. But that’s also going to mean maybe less income. It’s going to mean, more responsibility. The artist has to take more responsibility because suddenly they have more freedom.

These are all going to be things we’re going to have to learn and figure out. We may have a perfect model in three or four years or maybe 15 years. I can’t tell you. Right now, we are in the thick of it turning itself upside down. It’s very uncomfortable for people like me. And it’s confusing for all the older farts who want everything to stay the same.

It’s really weird. There are huge ups and huge downs. Well, perceived downs. I think it’s really positive. The roughest part for any of us is that, the old model, if you were part of the “club,” so to speak, you could figure out a way to get the bills paid.

The only reason money has to be exchanged is because money is how we provide for the basics in our lives. As far as I’m concerned, music should never be paid for. It should all be exchanged. . . it’s no different than standing in front of your friend and singing a song and dancing. You don’t go, “Hey, check out this new song I wrote” and after you’re done, say, “Okay, that will be four dollars.”

Popshifter: (laughs)

Roger Manning: You were giving a gift to your friend. And if they enjoyed it, they sang along. It’s reciprocal and it’s an exchange. That’s all a record is. Or a live show or a DVD. But that control mechanism has to be in place so that there can be some level of, “Thank you for your effort. Here’s your compensation. Now go buy your five-dollar-a-gallon gas.”

Popshifter: (cracks up)

Roger Manning: That’s what the old model was. For better or worse, we had a setup that worked. Now the setup is being turned on its head and music is being treated very… well, a lot of its specialness and uniqueness is being devalued through piracy.

See, by the same token I just said music should be exchanged freely. So what is the larger question? It becomes, how do artists get compensated for what they do? Because it takes so much goddamn time to write and record the music, put a show together, etc. But you’ve gotta give me and everybody else who does this some kind of compensation so we can pay our bills. That’s it. As soon as we figure that part out, I have no problem how music gets exchanged.

That’s what we’re all learning to figure out. I’m not one of these guys running around going (adopts old fart voice), “You remember when we were little kids?” No no no no. That was fine for them, but change is always going to happen. It’s going to continue to evolve.

I love the fact that recording a quality record is so affordable now that some little kid, some 14-year-old, in his mom’s basement in Jacksonville, Florida whom I’ve never met, could be making the most brilliant pop or dance record that the world has never heard. And 20 years ago, in the old model, he couldn’t have done that because he couldn’t have afforded it.

Chances are he would’ve never been able to get himself out of his environment if he wasn’t born into some kind of affluence, to get enough capital together to start his own band to then do that whole thing that you had to do to get signed.

Now, he saves up $500. Literally, with $500 he can make a state-of-the-art record that is sonically as good as the latest Radiohead record. That is, flat-out, a miracle. To see that in my lifetime, to see both extremes in my short lifetime. That’s cool as hell.

Popshifter: I agree.

Roger Manning: So that the Drum Buddies of the world can have a voice. So Michael Stipe can say, “Wow, the latest Quintron [record] is blowing my mind.”

Popshifter: (laughs)

Roger Manning: And you can buy the Quintron record next to R.E.M. on iTunes. That is a great, great thing. That is progress in all the best senses of the word. That’s the part of this rebirth that I welcome. But figuring out the rest of it is what we’re going to collectively have to come to an agreement on.

And right now there are no ideas that everybody is agreeing on. A lot of people are throwing stuff out there but nothing is solving the riddle 100 percent or even 90 percent. (laughs) It’s all figuring out a piece of it. And maybe that’s what it will be. Ten years from now it’s ten different pieces from ten different ideas.

Popshifter: You said on your website that Albhy Galuten [who produced Jellyfish, as well as the Bee Gees, Eric Clapton, Barbra Streisand, and others] gave you some advice once. He said “just do what you’re passionate about with honesty and sincerity and the rest will take care of itself.” I find that pretty much everything that I put on Popshifter has that theme. A lot of the people we’ve had interviews with, like David Markey or Vicki Berndt—

Roger Manning: Two of my heroes.

Popshifter: —has had a version of that same statement. Would that be your advice for anyone wanting to work in music, either writing or performing?

Roger Manning: In many ways, that statement now, to me, at age 42 seems totally obvious.

Popshifter: Ten years ago, I would have never thought of that.

Roger Manning: Right. When Albhy said it to me, I thought it was one of the most brilliant and insightful things I’d ever encountered. Our culture, we are born into a culture that basically says, the world is a totally scary place filled with nothing but scarcity. And you have to do whatever it takes, even if it’s against your better judgment, even if it’s against all logic, and even if it’s against everything that your heart is telling you. You should do it anyway for survival. Because if you don’t have this thing called money, you’re not going to have freedom.

Freedom Mall, Charlotte NC

You’re not going to have the basic essentials to put a roof over your head and food on the table. And you’re not going to have what our culture calls “true” freedom, which is the ability to go down to the mall—

Popshifter: (giggles knowingly)

Roger Manning: —and purchase the illusion of these material objects that people are told are going to make them happy. So, excuse me while I get on my soapbox—

Popshifter: Oh, I’m on that soapbox every day.

Roger Manning: —but to answer a lot of the questions you’re asking, they go beyond music. They go to societal and cultural values, here in America, especially.

I learned very early on, unlike my parents’ generation and a lot of my peers, it was quite apparent to me that I had no interest in starting a family. And if I did, I was like, “Well, I’ll just deal with that in my 30s.” So in my college years, it was like, I can just get enough money together to cover my own ass, I can pretty much do what I want.

I’d had enough shitty jobs, as we all did early on; we took whatever we could to pay for gas in our car, any of the privileges our parents were giving us, we had to pay for. So I had my hardware store jobs and every one of those jobs—and I think this is the plan of any wise parent—shows the kid that they’d better figure out what they really want to do, because they don’t want to do this for the rest of their life.

Popshifter: (laughs)

Roger Manning: For any of you working at a hardware store, I have no desire to insult any of the people in the goods and services field. We’ve all dealt with great hardware store attendants and real jerks. And the great ones are the ones really into their jobs: they know all about the equipment, they’re very eager to help you, and get you on your way.

Peter Gabriel, 1974

Now the world would not go around without them, so don’t take them for granted. I just used that as an example that was quite immediate to me, that there was no way I could align myself with. It was not going to fulfill me. We are all creative beings: the basketball player, the musician, the real estate agent, the banker, they are all creating and expressing themselves through their work. I don’t hold any one job in higher esteem than the other.

It was clear to me early on that when I felt correct, when I felt normal, when I felt like there was a reason to get out of bed in the morning, it involved something musical. And the more I did it, the more fulfilling it became and the better I got at it. So I was like, if I could just figure out the jigsaw puzzle to have my cake and eat it, too.

It was a very weird time because a lot of my heroes were weird bands like the Talking Heads or Peter Gabriel. Who in my opinion were doing very weird music, but it was in the confines of pop. And they were on the radio and they were selling records. They weren’t selling as many records as Madonna, but they were still selling a buttload of records. And they were able to make their weird, Art School pop and still reach middle America.

And I was like, well, if they can do it, I should at least be able to figure out my own version of that. That was my goal. I was like, how do I do what I want to do, which I knew wasn’t middle-of-the-road dance pop. That was my loose game plan getting out of college. That was my dream.

The mere fact that Jellyfish got signed to a major label and we were making our very unpopular, un-trendy pop at the time. We debuted in the middle of grunge and hair metal. The fact that we had gotten even that far, to me, I had almost succeeded right there.

Because I was like, this is a fucking miracle.

(We both laugh.)

Roger Manning: That somehow Andy and I concocted our own unique brand of pop and convinced a major corporation to take a chance on it. And when I walk into some record store in Germany I can see it on the shelf. With our silly picture and it says co-written by me. Fucking miracle.

Test shot from British photo session.

Popshifter: (laughs again)

Roger Manning: That little moment was proof to me that if I just thought it out and was strategic about it, but also simultaneously balanced that kind of business, entrepreneurial side with that very flighty, often-not-grounded creative side, that’s just spouting all kinds of ideas left and right. If you marry the two in some kind of focus, everything I was going to be involved in—as long as I tried to keep Albhy’s words at the forefront—it was all going to take care of itself.

Because I think a fan really picks up on integrity from an artist. The more you value and love yourself and what you have to offer with all of its apparent flaws, or its apparent judgements and incredible uniqueness, once you establish peace with that as an artist, and you really understand yourself and value yourself. . . all these things that I didn’t know how to verbalize or articulate, and I’m still not doing a very good job—

Popshifter: (laughs)

Roger Manning: At least I understand it now. Once you say, “I appreciate this and given the chance, so will you.” I’m not saying everybody has to come to my party, but I’ll bet that there are a lot of you that are going to want to. And that’s exactly what has happened.

I don’t have a huge fanbase anywhere. Jellyfish didn’t either. What we have are pockets of super-dedicated, die-hard fans who get it. All over the world. To this day, those are the people who appreciate what I do. Collectively they add up to a nice little family that I’m trying to figure out ways to increase every day. Trying to get more of that news to the people who may have not heard it yet.

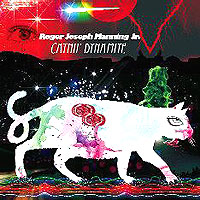

Catnip Dynamite

For every new thing I put out—like the Morrissey record I play on or my alter ego Malibu—how do I take advantage of the new technology to get to the stranger in India who has no idea of what I offer, or what Vicki Berndt offers, or David Markey offers or the Steve McDonald solo band offers?

Because I guarantee there is a population of the East Indian or Chinese or Russian people that are going to dig it. If the Beatles proved anything, they proved that the language of sing-along pop transcends all cultural barriers and language barriers. You could almost argue it’s a religion that people around the world subscribe to

Popshifter: Oh, I wouldn’t argue that it isn’t!

Roger Manning: And that’s the language that I speak: sing-along pop. I’ve been in the top ten on Japanese radio. I was never in the top ten in the English speaking world. So go figure!

I’ve had the best radio success ever in my career with the most recent record that came out in Japan in March. [Catnip Dynamite] I had more top ten Japanese radio ads than Jellyfish ever did. I can’t explain this! Other than I must be speaking a language that a lot of people are relating to.

That just tells me, keep doing more of it! Stay on that path. If that path has meant me taking a chance in foregoing some of the things that I knew were going to be guaranteed money—and they were also creatively pleasing—but I knew that working on my own music was going to be even more creatively fulfilling, and really complete that part of me that felt frustrated, like I wasn’t able to share what was going on inside me with the world musically. That’s what these solo records came out of.

In doing them, I’ve rekindled with these fans around the world. People are coming out of the woodwork, like you: “I saw you guys 20 years ago and my god, I can’t believe now there’s new music for me to check out.” Obviously it’s not Jellyfish, nor is that its goal, but that part of Jellyfish that was my personality, that fan is relating to. They’ve been very complimentary and I couldn’t be happier that at my age, I’m getting to do this.

Additional Resources:

For the latest information on Roger, including where you can purchase Catnip Dynamite and other music, please visit his official site. To order the new TV Eyes EP, Softcore, which also features a limited edition DVD, please visit the CD Japan TV Eyes page.

3 Responses to “Speaking The Language Of Pop: An Interview with Roger Joseph Manning, Jr.”

August 1st, 2008 at 1:08 pm

[…] https://popshifter.com/2008-07-30/speaking-the-language-of-pop-an-interview-with-roger-joseph-manning… […]

January 30th, 2009 at 11:04 pm

[…] Speaking The Language Of Pop: An Interview With Roger Joseph Manning, Jr., Popshifter July/August 2008 Issue […]

June 7th, 2013 at 4:36 am

[…] Wrong” & “Baby’s Coming Back”. Roger talks about getting Steve in a Popshifter interview: “Yeah, we’d been fans for years. The running joke was that in finding the other musicians […]

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.