Waxing Nostalgic Connecting The Dots: Jim Steinman, “Bad for Good”

Published on November 6th, 2013 in: Music, Waxing Nostalgic |Let us now sing the praises of those who have gone previously unsung.

I didn’t get to see my sister, Winter, much when I was a kid. My dad’s daughter, she lived across the river in mysterious Ohio. I would get to see her once or twice a month. After she began driving and discovered the mysterious joys of high-school penis, it was even less than that. She was the one, however, who took me to see not only Purple Rain, but Grease 2. I’m not sure which one made more of an impact. Sure, Apollonia Kotero had amazing breasts, but I still remember all the words to “Reproduction” and “Do It for Your Country” from Grease 2.

Puberty sucks. Everything leaves its mark.

Winter’s musical taste tended towards the progressive and theatrical. I have never known anyone else, even to this day, who has owned a Marillion album. Winter did. She had every Electric Light Orchestra record. She had a love for the concept album that most certainly informed my own. There was one album in particular . . . and we’re getting to it.

Waxing Nostalgic Connecting the Dots: Pat Benatar, “My Clone Sleeps Alone”

Published on October 30th, 2013 in: Music, Waxing Nostalgic |Here it is. This is the first LP I ever bought. My first record!

Oh, I had gotten musical gifts before, sure. I got The Stranger by Billy Joel, and I still know all the words to “Scenes from an Italian Restaurant.” I had a copy of AC/DC’s Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap. I don’t know where that came from. I don’t remember asking for it. Regardless, there it was in my collection, “Big Balls” and all.

But, this! The first album I chose with my own amazing ten-year-old choosing powers! Empowering! Enlightening! Embiggening!

Women in rock and roll weren’t a new thing for me, even in such a male-dominated genre as Seventies rock. I was familiar with Janis Joplin, of course, and I knew that Blondie was the name of the band, not the lead singer.

But the first time I heard “Heartbreaker” on FM radio, it hit me hard. It was one of the rockingest things on the radio that year, when the airwaves were filled what fools believe and grown men asking if I liked piña coladas. “Heartbreaker” was a much-needed boot to the head.

Waxing Nostalgic Connecting The Dots: Fleetwood Mac, Rumours

Published on October 23rd, 2013 in: Music, Waxing Nostalgic |1977 changed everything. Whether you think of it as The Year Punk Broke or The Year Star Wars Came Out, 1977 flipped the game, changed the rules, and destroyed the playing field.

It was released on February 4, 1977. I don’t know precisely when Fleetwood Mac’s album Rumours entered the household, but once it was there, it seemed like it always had been. It settled in, immediately becoming part of the fabric of the house. It was the aquarium. It was the faux brick finish in the kitchen. It was “Second Hand News.” It was the green shag carpet. We put the album on, made it a pot of coffee, and sat down around the kitchen table for donuts, gossip, and “Gold Dust Woman.”

Waxing Nostalgic Connecting the Dots: Kansas, “Carry On, Wayward Son”

Published on October 16th, 2013 in: Music, Waxing Nostalgic |I grew up listening to the Moody Blues, so I was no stranger to pseudo-mysticism and lyrics that some people would consider “heavy.” In third grade, I knew what The Lost Chord was. I understood revolution in the streets as well as how to call occupants of interplanetary, most extraordinary, craft. Was I a weird kid? Were all pre-teens in the Seventies like that?

Maybe we were all weird kids, regardless of when we were born.

Carry on, my wayward son . . .

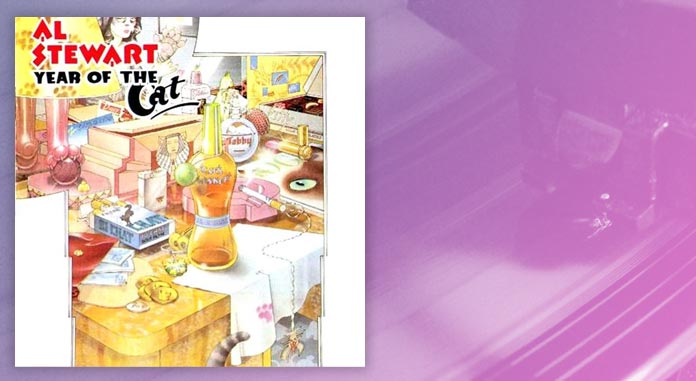

Waxing Nostalgic Connecting The Dots: Al Stewart, “Year of the Cat”

Published on October 9th, 2013 in: Music, Waxing Nostalgic |At the age of eight, I stopped hearing music and began actively listening to it. Matching artists with their music became a thing of great importance. I needed to know lyrics. I began learning the names of everyone in a band, not just the attention-hogging lead singer. It was the next phase in becoming a real music fan. I wanted to listen to as much music as I could, as many different kinds as possible and all of it, faster than now.

At that age, I developed more fears than I conquered. There were certain songs that, for reasons difficult to pinpoint and harder to explain, scared me. My abandonment issues and fear of sounds in the night were blooming like nightshade. My love of music corresponded with that and mirrored it. Good thing I didn’t collect creepy porcelain dolls.

This brings us, strangely enough, to Al Stewart’s seven-minute pop opus, “Year of the Cat.” The song is a weird fusion of smooth jazz and progressive pop. The lush orchestration belies the stark piano part that takes the spotlight shyly, almost with embarrassment. This is secret music, played from far away.

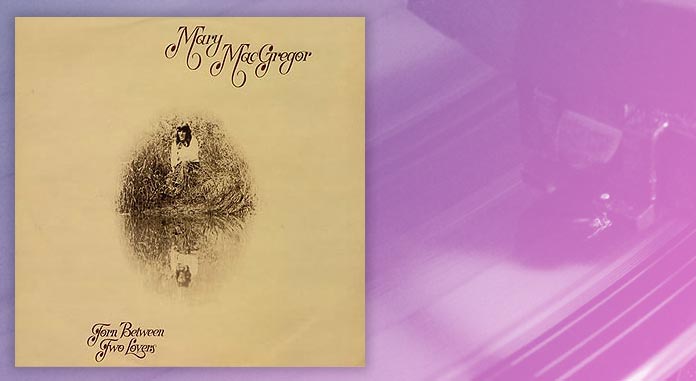

Waxing Nostalgic Connecting The Dots: Mary MacGregor, “Torn Between Two Lovers”

Published on October 2nd, 2013 in: Music, Waxing Nostalgic |1976 was the year of America’s 200th birthday. We walked smugly around our little town in ugly red, white, and blue shirts. We shot off fireworks while Europe rolled its eyes and told us to stay the hell of its lawn. Jingoism, patriotism, and parades were the order of the summer. Eagles and sno-cones, commemorative quarters and flags, colors that refused to run. We picnicked under the shadow of thousands of unseen missiles, our thin windbreakers and bravado enough to shield us from the chill of the Cold War.

As fall crept in and the charcoal grill fires slowly died, something insidious began to snake its way through the country. I see it now as a virus, its simplicity masking its evil intent. By the time winter rolled around, we were all infected. We wouldn’t be the same for years.

You know what 45s were, right? They were like full-length vinyl records, except they were singles. One song per side, and they had to played at a faster speed then LP’s, for reasons that I don’t know enough science to fully comprehend. The first 45 I ever bought was Mary MacGregor’s “Torn Between Two Lovers.” I was seven years old.

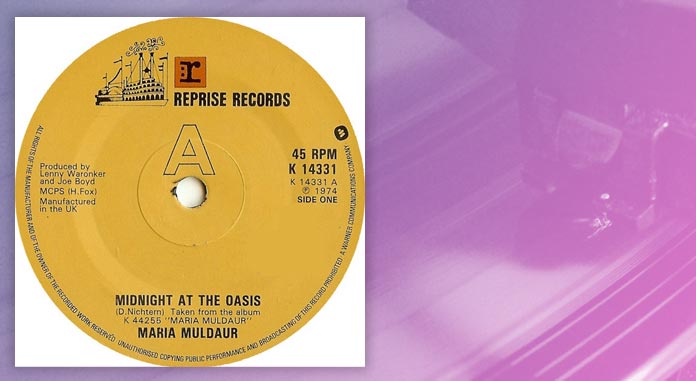

Waxing Nostalgic Connecting the Dots: Maria Muldaur, “Midnight at the Oasis”

Published on September 25th, 2013 in: Music, Waxing Nostalgic |When the Sixties ended, they made a noise like a whoopee cushion. Peace and love were replaced with polyester and The Sierra Club. Even The Beatles said to hell with it and bailed out before the Seventies really got rolling. A lot of people got tired of Serious Rock, and in response to the backlash, the music business gave us a lot of bubblegum pop. It was sweet and nice with nary an iota of substance. We got lots of one-hit wonders this way.

The first time I remember hearing “Midnight at the Oasis” was in a hair salon. I was waiting for my mother to get whatever the hell she was getting done, done. I was five years old. I could already read at a high school level (math was a different story), and I had already flipped through all the magazines that interested me. The hairdressers were yammering on about what pains in the asses men were. Hairdryers hummed away.

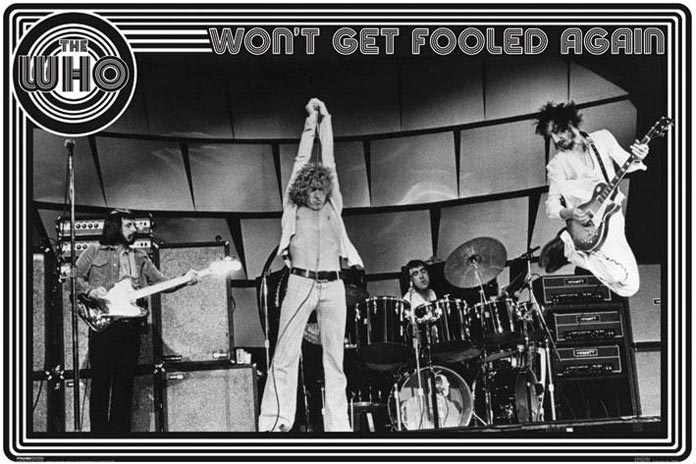

Waxing Nostalgic Connecting The Dots: The Who, “Won’t Get Fooled Again” (1971)

Published on September 18th, 2013 in: Music, Waxing Nostalgic |The John A. Roebling Suspension Bridge connects Covington, Kentucky (the town of my birth) to Cincinnati, Ohio (the town that, as a teenager, became my stomping ground). At the time of its completion, in 1866, it was the longest suspension bridge in the world, with a span of 322 meters (1057 feet).

Let’s get down to brass tacks here. Driving over the Suspension Bridge is scary as shit. As soon as you hit the surface of the bridge, the road surface changes. No smooth blacktop or asphalt here; it is nothing but closely spaced thin strips of steel. That’s all keeping you and your car from pulling a Mothman Prophecies and plunging hood-first into the Ohio River. When you drive over it, the car begins to vibrate, and this hideous hum begins emanating from your tires. Rubber meets metal, and the entire vehicle shakes and swerves.

It’s not pleasant.

Unless you’re two years old and don’t know any better.

Here’s the odd thing. Depending on how fast you go, the friction of the bridge against the tires produces a musical note. I know for a fact that as my mother drove across the bridge that day, she was playing an open A chord without realizing it.

Waxing Nostalgic Connecting the Dots: Phasing

Published on September 11th, 2013 in: Music, Waxing Nostalgic |In 1971, I was two years old the house was awash in mild psychedelia. We had an aluminum Christmas tree, all silver. The branches were metal spikes that fit into a pre-drilled steel tube. Reflective bits of Mylar replaced the false pine needles. We also had a color wheel, four plastic cels of colored plastic revolving slowly in front of a bare light bulb. Groovy? Yeah, man.

The living room awash in color, my father had the music playing as usual. I was sitting on the couch under my own power, which was a relatively new thing for me. The speakers were huge and he liked it loud. He took a sip from his drink, looked at me levelly, and said, “Phasing.”

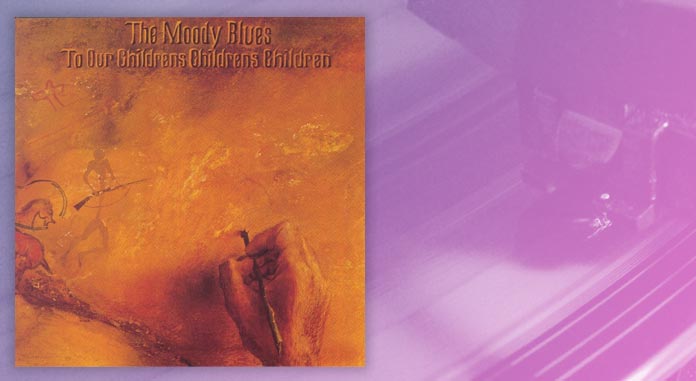

Waxing Nostalgic Connecting The Dots: The Moody Blues

Published on September 4th, 2013 in: Music, Waxing Nostalgic |I can’t remember the first song I ever heard. It seems like very few people would. I can remember the first song I remember hearing, but I know that’s not the first song I ever actually heard. There’s no way to divine the actual first piece of music I ever heard, but I can get close.

From what I’m able to gather, the first album my parents bought after I was born was To Our Children’s Children’s Children by The Moody Blues. That record came out in November of 1969. I came out in June.