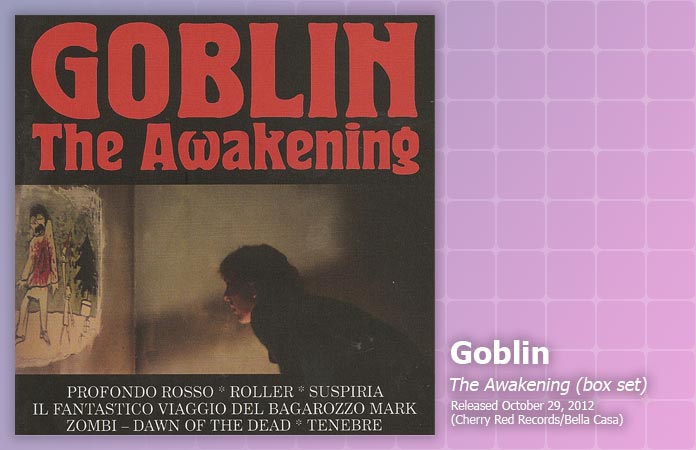

Music Review: Goblin, The Awakening (box set)

Published on February 8th, 2013 in: Current Faves, Horror, Music, Music Reviews, Retrovirus, Reviews, Soundtracks and Scores |

If you’ve seen Suspiria, then you know of Goblin, the Italian band responsible for its iconic, eternally terrifying score. There have been lineup changes over the years, but several members have been consistent: original members Massimo Morante and Claudio Simonetti, in addition to Maurizio Guarini, Agostino Marangolo, Walter Martino, and Fabio Pignatelli.

Fans of filmmaker Dario Argento may already be familiar with Goblin’s contributions to the Italian horror and giallo genres, but Goblin has much to offer the music aficionado looking for something challenging. In keeping with the spirit of their prog rock origins, they have several albums that are not scores, including at least one straight-up concept album, sort of like a soundtrack without a movie.

Cherry Red Records and Bella Casa have compiled an excellent sampling of Goblin’s bizarre and enthralling discography with a six-disc box set including not only the band’s compositions for Argento films, but also their contributions to the prog rock pantheon.

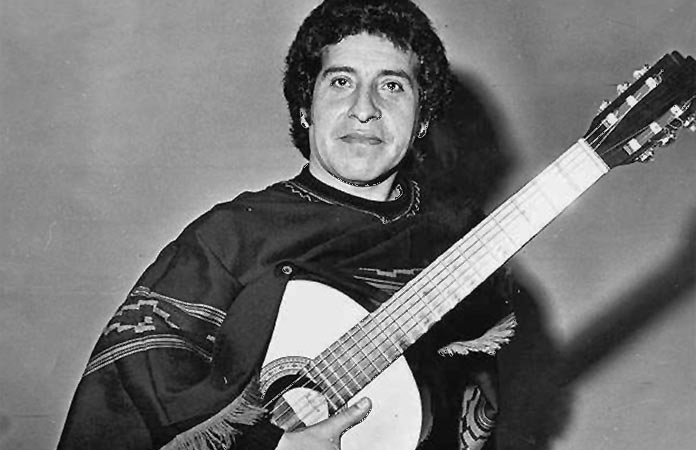

Miercoles con Víctor Jara: Una Introduccion

Published on February 6th, 2013 in: Culture Shock, Current Faves, Music, Retrovirus |

Time stopped when I first heard Víctor Jara sing. One of my favorite podcasts, Alt.Latino, had included Jara’s music in an episode that looked at protest music from across Central and South America. Jasmine Garsd, the podcast’s co-host, had preceded his song with a description of his importance in his native Chile and his brutal murder at the start of the Pinochet regime. As disturbing and poignant as this biography was, nothing prepared me for the beauty of his music.

The needle dropped on “Un Derecho de Vivir en Paz,” Jara’s song in protest of the Vietnam war. Over a bed of harpsichord and arpeggiated guitar, Jara sang in a disarmingly straightforward voice. His tenor had a reedy tone and a substantial quality that anchored the melody. Like many of its North American counterparts, the song had a memorable melody that could invite singalongs. Where many songwriters north of the border tended towards straightforward production however, Jara’s song featured a psychedelic instrumental break in which a ragged guitar freakout alternated with a bobbling analog synth part. The song ended with what sounded like a spontaneous choir of “la la la”s, which reinforced the spirit of community for which Jara’s time was known. As understated as Jara sounded, a current of sadness and hope ran through his voice, and that emotion made me want to listen to it again and again.

After hearing about his grotesque death, I found myself wanting to see Jara as he was alive. Some excerpts from a live concert he performed for Chilean television came up on YouTube. Seeing and hearing this man, with his steady, weathered voice and his everyman appearance, made him more real for me but also made the tragedy of his death that much more palpable. I was drawn to the honesty of his voice and the lyrics I could understand, but the experimentation in his music beguiled me as well.

In time, I was able to get a boxed set of Jara’s albums through inter-library loan, as well as a copy of An Unfinished Song, the biography his wife Joan wrote about him. I also have been attempting to read The Shock Doctrine to better understand the Allende administration and how Pinochet came to power. Through my interest in Jara I learned that two bands I quite like have paid tribute to him in song—Joe Strummer name-checked him on Sandinista! and Calexico recorded a song called “Víctor Jara’s Hands.”

In spite of these tributes and the praises of other big-name fans, Jara is not well known in the States. To that end, I will be working through his discography and writing reviews for Popshifter when time permits. Víctor Jara created music that both spoke to the people of its day and is still prescient in this day and age. His work deserves a larger audience and I’d like to do what I can to encourage readers to track down his music.

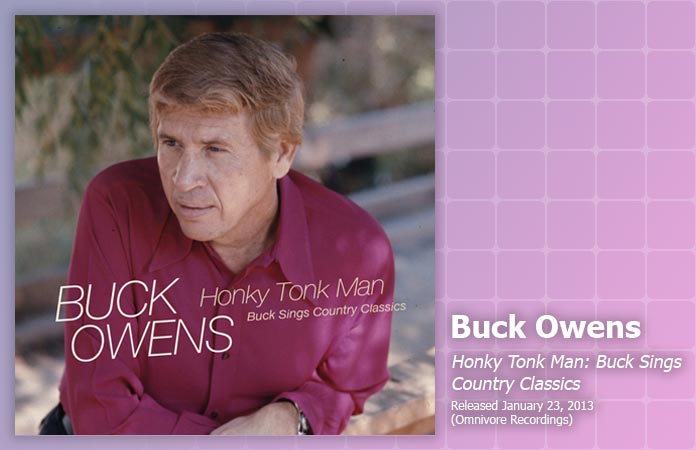

Music Review: Buck Owens, Honky Tonk Man: Buck Sings Country Classics

Published on January 23rd, 2013 in: Current Faves, Music, Music Reviews, Retrovirus, Reviews, TV |

Another gem appears from the Buck Owens vault. Honky Tonk Man: Buck Sings Country Classics is a collection of musical backing tracks from Hee Haw with Buck’s reference vocals over them, which sounds like it wouldn’t be a treasure at all. But let me back up a moment.

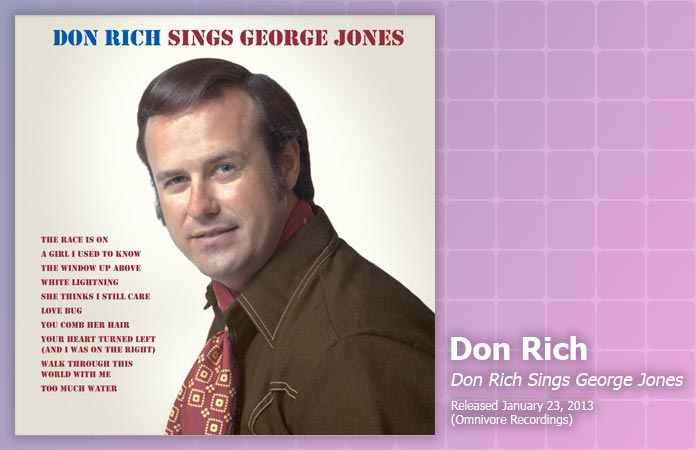

Music Review: Don Rich Sings George Jones

Published on January 23rd, 2013 in: Current Faves, Music, Music Reviews, Retrovirus, Reviews, TV |

Some people fantasize about going to Shangri-La, some people dream of winning the lottery. Me? I dream of going to Buck Owens‘s tape vault. Until a couple of years ago, it never crossed my mind, but with 2011’s release of Buck Owens’s Bound For Bakersfield collection of pre-Capitol demos (review), and now with the dual releases of Don Rich Sings George Jones and Buck Owens’s Honky Tonk Man, I want to go there. I cannot get my head around the fact that Don Rich’s lone solo record languished in the vault for 40 years. I can’t help but wonder what’s left in there, and desperately want to find out.

Don Rich was Buck Owens’s right hand: his guitarist, fiddler, and the man who brought harmony—a high tenor over Buck’s high tenor—to his tracks. They had an uncanny, beautiful way of harmonizing. Don’s smiling presence on Hee Haw, just over Buck’s shoulder, is my favorite thing about the show. Okay. That sounds a bit like fan fiction. Note to self: Don’t look that up. Ever.

Music Review: Shoes, 35 Years—The Definitive Shoes Collection 1977-2012

Published on January 15th, 2013 in: Current Faves, Music, Music Reviews, Retrovirus, Reviews |By Cait Brennan

By any measure, 2012 was a banner year for the pioneering power pop rockers Shoes. For decades, the band has hewed its own indie path through pop music, with a strong DIY ethic that helped kick start the home-recording movement decades before Garageband made it easy. Back together in the studio for the first time in 17 years, brothers John and Jeff Murphy and their high school pal Gary Klebe joined with drummer John Richardson for Ignition, a spectacular new album of originals that reestablished Shoes as power-pop masters and made its way onto a number of critics’ year-end best-of lists (review). They were the subject of a new biography, Boys Don’t Lie: A History of Shoes, and their first four pre-Elektra albums—One In Versailles, Bazooka, Black Vinyl Shoes, and Pre-Tense (the Present Tense demos)—were issued on vinyl in gorgeous deluxe editions by the Numero Group.

Truly, it’s never been a better time to be a Shoes fan. But for those who haven’t yet joined the cult of Shoes, it might seem a little daunting to find a way in to a band whose widely acclaimed output stretches to at least 180 songs on 17 albums recorded over a 38-year period.

Real Gone Music has this problem sorted with its excellent new disc 35 Years—The Definitive Shoes Collection 1977-2012. From their ’77 breakthrough Black Vinyl Shoes all the way through Ignition, it’s a great survey of some of the finest moments of their career, and the perfect place to start a Shoes safari.

Music Review: Crime & the City Solution, A History of Crime – Berlin 1987-1991: An Introduction to Crime & the City Solution

Published on January 9th, 2013 in: Current Faves, Music, Music Reviews, Retrovirus, Reviews |By Julie Finley

Being a longtime fan of Crime & the City Solution, I was already familiar with all of the tracks on A History of Crime. However, the albums in their discography aren’t easy to find, and are more than likely out of print, so if anyone ever had a fleeting interest in this band, but can’t get their hands on their albums, this release bridges that gap. A History of Crime is a grand collection of Crime & the City Solution’s works, and doesn’t disappoint. However, the one major flaw is that it only includes music created between 1987-1991. I mention this because the pre-1987 output contains some of my favorite songs.

Best Of 2012: Chelsea Spear

Published on December 20th, 2012 in: Best Of Lists, Books, Music, Retrovirus |Say you’re a rock critic and the calendar has dwindled to a single page. You’re expected to write a year-in-review column, but your artistic heroes have disappointed you and none of the year’s new releases have galvanized you the way you’d hoped. What do you do? You reach into your back pages to look at some forgotten favorites and things that got away from you the first time around. In writing about these forgotten favorites, maybe you can introduce your readers to something new as well.

Best Of 2012: Emily Carney

Published on December 18th, 2012 in: Best Of Lists, Movies, Music, Retrovirus |

1. Music: The Very Best of Vince Guaraldi, The Very Best of Bill Evans, and The Bill Evans Trio, Moon Beams

In the last year, Concord Music Group re-released and compiled great jazz collections for those into mid-century modern jazz. The best offerings included Vince Guaraldi’s Peanuts-infused classics and Bill Evans’ elegiac piano stylings. Moon Beams may be one of the saddest jazz records of all time, but it has some of the most elegant, beautiful piano chord progressions recorded in music history.

The Vince Guaraldi Trio, A Charlie Brown Christmas

Published on December 13th, 2012 in: Current Faves, Holidays, Music, Music Reviews, Retrovirus, Reviews, Soundtracks and Scores, TV |

The tinkling piano lines, rolling brushed drums, and sprightly tempos of Vince Guaraldi’s soundtrack to the classic TV special A Charlie Brown Christmas are a welcome sign of the holiday season. Guaraldi’s keyboard treatments of classic Christmas songs like “Greensleeves,” “O Tannenbaum,” and the classic children’s choral arrangement of “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing” give these classics a new sound. Some of his originals, such as “Christmas Time is Here,” portray the loneliness and melancholy of the holiday season though a few minor chords and a contemplative melody. Other new songs, like the bright, upbeat “Linus and Lucy,” sound like the rush of energy you sometimes felt as a kid around the holiday.

Music Review: Bert Jansch, Heartbreak

Published on November 20th, 2012 in: Current Faves, Music, Music Reviews, Retrovirus, Reviews |By Cait Brennan

Trying to name the greatest guitarist of all time is a fool’s errand. One, because it would be impossible to choose a single player from a slate of candidates as diverse as Django Reinhardt, Andres Segovia, Jimmy Page, Lindsey Buckingham, Prince, Richard Thompson, Mick Ronson, George Harrison, Ron Asheton, Don Rich, Brian May, Frank Zappa, etc, ad infinitum. And two, because the answer is Bert Jansch.

Fine, reasonable souls may disagree, but from his stunning masterpiece of a debut in 1965, Jansch blazed a staggeringly original trail through an eclectic mix of folk, jazz, blues, rock, and even African, medieval, renaissance, and baroque music. Whether solo or with his band Pentangle, his highly distinctive playing and his warm, earthy vocals made him a major influence on everybody from Jimmy Page, Neil Young, Nick Drake, Donovan and Mike Oldfield to Paul Simon, Johnny Marr, Graham Coxon, Bernard Butler, and so many more. Bert died in 2011, doing what he did best till the very end.