The Intercontinental Title Podcast, Episode #01

Published on December 4th, 2015 in: Pro Wrestling |Welcome to the latest podcast in the Popshifter family, The International Title Podcast.

This weekly podcast covers the WWE, both presently and historically. Hosts Jeffery X Martin and Paul Casey also take a look at the larger questions involved with the business, such as how it impacts popular culture.

Does NXT Hold The Key To The Future Of Wrestling?

Published on November 9th, 2015 in: Pro Wrestling |By Paul Casey

NXT is ostensibly the minor leagues of WWE; in reality, it is so much more than that.

I have watched wrestling for a long time; over 20 years. And I don’t know if I have ever been so hopeful for the future of the sport than I am now. Triple H has assembled a rich group of talent, combining Indie veterans and entirely new creations, many from sports backgrounds. NXT is filmed in the Full Sail University—WWE’s training ground—in Florida and the crowd has the old ECW feel, only without the misogyny and blood lust. This is a kinder, more mature audience who are just as likely to appreciate a great women’s match as they are a kendo stick extravaganza.

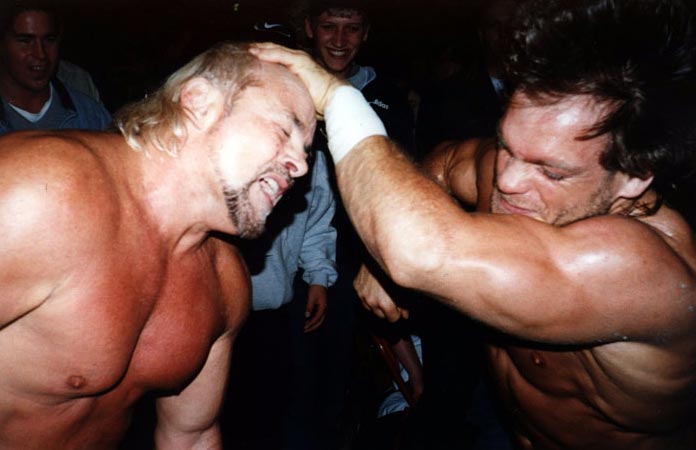

Dusty Rhodes: Farewell to the American Dream

Published on June 19th, 2015 in: Pro Wrestling |“If you don’t have an ego and you don’t have a goal, you ain’t worth a damn.”

—Dusty Rhodes

Dusty Rhodes had an ego the size of Pangaea and when people called him The American Dream, it wasn’t just some wrestling hyperbole nickname. The man lived the American Dream. He embodied it. And while it’s cute and ever so arch to talk about his passing as “the death of the American Dream,” in a lot of ways that’s absolutely accurate.

DVD Review: Wrestling With Satan

Published on February 6th, 2015 in: Culture Shock, Documentaries, DVD, DVD/Blu-Ray Reviews, Movie Reviews, Movies, Pro Wrestling, Reviews |One of the fascinating things about Christianity is you can do anything and call it a ministry. Hand puppets. Being a clown. Fixing cars. Shaving. Do it in the name of Jesus Christ, and it is a fully sanctioned activity done for the benefit of the Church Universal.

It makes sense, therefore, that there could be a professional wrestling ministry. The documentary Wrestling with Satan spotlights a six-year period in the history of the Christian Wrestling Federation (CWF). Led by the charismatic Rob Vaughn, who performs under the name “Jesus Freak,” the CWF is an actual independent wrestling company. His stable of wrestlers is highly trained and works well in the ring. Wrestling fans will appreciate the fact that the only special feature on the disc is comprised of seven bonus matches.

Blu-Ray Review: No Holds Barred

Published on April 4th, 2014 in: Blu-Ray, DVD/Blu-Ray Reviews, Movie Reviews, Movies, Pro Wrestling, Retrovirus, Reviews |When I was little I saw the cover for No Holds Barred countless times but never watched it because I really wasn’t into wrestling. When I was in my early teens I got a little into wrestling for a year or so, but then just got bored with it all. So as you can see, I’ve never been into wrestling and just don’t understand its following.

How Wrestling Can Modernize

Published on September 5th, 2013 in: Pro Wrestling, Sports |By Paul Casey

“Fantasy is hardly an escape from reality. It’s a way of understanding it.”

—Lloyd Alexander

If you’ve read any of my wrestling based writing over the last couple of years, you know that I believe professional wrestling/sports entertainment is as good as place as any for creativity. I am not a casual fan and have devoted many hours and dollaroos, and on occasion have even attempted to apply a figure-four leg-lock to humans and actually make it hurt (unfortunately impossible to do).

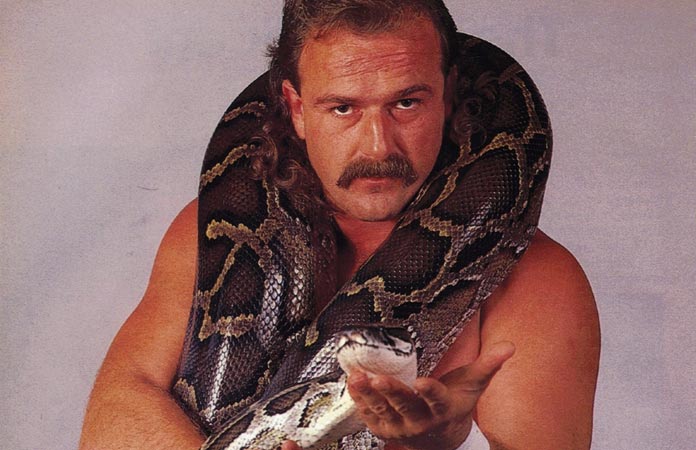

The Redemption Of Jake “The Snake” Roberts

Published on February 18th, 2013 in: Pro Wrestling |By Paul Casey

Jake “The Snake” Roberts, for those who do not know, was one of the greatest bad guys in wrestling. One of the most gifted talkers in the business, Jake made you believe more than most. As with other legendary heels like Ric Flair, to work with Jake meant nearly instant credibility for a good guy. He not only inspired genuine hatred, but also fear, especially from younger members of the audience. Inside the ring, Roberts was a creep, a sneak, and a cheat. Outside of the ring he wasn’t too different.

Over his shoulder, he would carry a large black bag containing his pet Damien. A gen-u-ine Python who would come into play during or after a match. Roberts also had one of the best finishers around: The DDT, as elegant a move as has ever been used in professional wrestling. Starting from a front face lock, Jake would throw his body back, planting his opponent face first into the mat. While today the move has become as common as the suplex, Jake did it with great ceremony. The opponent would not flip over as they do now. They would go straight into the mat, or concrete, if Jake was feeling particularly serpentine.

Wrestling’s Dark Heart

Published on January 28th, 2013 in: Over the Gadfly's Nest, Pro Wrestling, Sports |By Paul Casey

One of the biggest problems for the modernization of professional wrestling, not covered in my last wrasslin’ bit, is the so called wrestling community. This especially concerns its Internet variant, which continues to be a barrier to any outsider views being able to filter through long enough to have any positive or lasting impact.

Why Wrestling Can’t Modernize

Published on January 8th, 2013 in: Over the Gadfly's Nest, Pro Wrestling, Sports |By Paul Casey

Wrestling is not a sport. It is some combination of martial arts exhibition, magic, and comic books. It is a dangerous profession. As I wrote around this time last year on Popshifter, there are many reasons why professional wrestling has not gained legitimate mainstream acceptance.

Over the last year in WWE—the most powerful wrestling outfit in the world—CM Punk, independent wrestling hero and one of the most gifted technicians in at least a decade, has held the main world title. He has held it for over a year, straight. In modern times this is extremely rare. In the old days title reigns lasted years; now they last months with a much wider pool of talent vying for the top prize. This is not really a bad thing—even though some would-be traditionalists argue that it has added to wrestling’s decline—as when the wrestlers in competition are talented and the bookers know how to weave storylines together it can reflect the best aspects of professional wrestling: fast, brutal, hilarious, and supremely athletic.

I have admired Punk for a long time, and when he shook up the company in 2011, it was an exciting time to be a wrestling fan. I hoped, as many did, that this would be the moment when wrestling finally moved on and progressed beyond emulating the successes it had in the past. Even though there have been many fine things about CM Punk’s run as the top guy in WWE (and arguably in all of pro wrestling), it emphasizes again how deeply ingrained wrestling’s problems are.

Suffering, Defeat, and Justice: Why You Should Care About Pro Wrestling

Published on January 30th, 2012 in: Issues, Oh No You Didn't, Pro Wrestling, Sports, TV |By Paul Casey

Professional wrestling reached the high water mark of its popular and critical acceptance in the late 1990s. Since then, the Internet has bypassed the crude elitism of the dirt sheets and allowed fans the world over to step inside the shoes of a failed sports journalist with a disregard for both style and skill. When Vince McMahon admitted the pre-arranged nature of professional wrestling, he hit upon a unique way to market his World Wrestling Federation. “Sports Entertainment” is an athletic display, a “male” soap opera, a comedy showcase, and supposedly has more in common with Saturday Night Live than it does with Greg “the Hammer” Valentine vs. Roddy Piper in a Dog Collar Match.

Lou Albano, Cyndi Lauper

This was probably true in the 1980s, when Cyndi Lauper was palling around with Lou Albano and Mr. T was teaming with Hulk Hogan. It was probably true in the late ‘90s when The Rock and Steve Austin were at the top of their game. We’re a living cartoon. We’re real life super heroes. We’re a magic show. The successful marketing term of “Sports Entertainment” was an obvious, calculated attempt to redefine a business which had fallen between the cracks of popular culture. “Do they really expect us to believe this is real?” Although people can appreciate the commitment of magicians such as Penn & Teller and David Blaine in maintaining the illusion, the confusion over what wrestling actually is led to a long period where the public liked to believe that they were simply too sharp to be fooled.