The Heart Of Darkness: Comedy And Drama From The Coen Brothers

Published on January 30th, 2009 in: Issues, Movie Reviews, Movies, Reviews |By Lisa Anderson

In 2008, Joel and Ethan Coen’s No Country For Old Men took home Oscars for best film, direction, supporting actor, and adaptation, as well as numerous other awards and critical accolades. This year, their follow-up caper comedy, Burn After Reading, garnered Golden Globe, BAFTA, and WGA nominations, before being passed up altogether by Oscar.

Speaking as a critic and a film fan, I appreciate the craft that went into both movies, but vastly prefer the first to the second. On the surface, both seem to have the characteristic Coen worldview, where nothing that happens has any meaning beyond itself. A closer look, however, reveals that the denizens of No Country For Old Men at least try to bring meaning to their own lives, even if they ultimately fail.

Josh Brolin as Llewellyn Moss in

No Country For Old Men

Both movies are about people who are trying to better their lives in questionable ways. In No Country For Old Men, Llewellyn Moss (Josh Brolin) thinks he is set for life when he finds a satchel containing $2 million. Never mind that the money was the focal point of a brutal drug-related shoot-out! In Burn After Reading, Linda Litzke (Fran McDormand) and Chad Feldheimer (Brad Pitt) seek to leverage their discovery of a disk of information about a former CIA operative. One difference emerges here: while Moss has something of objective value, Burn After Reading’s clueless gym employees have discovered nothing more valuable than household financial data and scraps of a badly written memoir. Moss wants to make life better for himself and his wife, while Litzke obsesses over elective plastic surgery procedures.

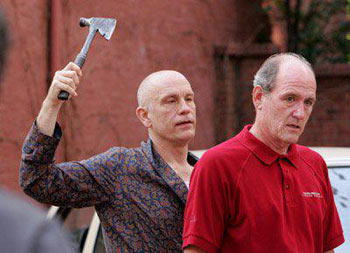

In both movies, the protagonists are opposed by vicious men intent on foiling their plans and defending their own interests: Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem) in No Country, and Osbourne Cox (John Malkovich) in Burn After Reading. However, hit man Chigurh is confident and competent, while Cox is an insecure, blustering caricature. In these ways, they are mirrors of their prey. Chigurh and Cox differ in their motivations as well. While Chigurh adheres to an outlaw code and his belief in fate, Cox is driven by self-interest and, late in the game, his irritation at everyone else’s perceived stupidity.

Both films feature characters who feel that time has passed them by. Sheriff Ed Tom Bell, played by Tommy Lee Jones, describes feeling “overmatched” by the evil of the modern world. Osbourne Cox is just barely young enough to have been a cold warrior, and he is part of an organization which has found its role shifting the past few years. Bell does his best to help the public, with tenderness, compassion, dignity, and humor. Cox, on the other hand, becomes increasingly ridiculous and abusive as he clings to his self-image. While it can be said that Bell gives into despair in the end, he is at least left standing. Cox is undone, first by addiction and then by his own violence.

John Malkovich (Osbourne Cox) and Richard Jenkins (Ted Treffon) in

Burn After Reading

Relationships are one key to what makes these two films ultimately feel so different. There are no loving relationships in Burn After Reading. At all. Both of the marriages depicted are affected by infidelity. Harry Pfarrer (George Clooney) strings along his mistress (Cox’s wife, played by Tilda Swinton), only to find, after breaking things off, that his wife has betrayed him, too. Linda Litzke dates a string of men who deceive her, but ignores and abuses the one man who could love her in the way she’s wants. By contrast, both of the marriages shown in No Country are characterized by tenderness and respect, even if Llewellyn Moss is more of an authoritarian than Ed Tom Bell. Nor is this trend confined to the marriages. Bell speaks with reverence and affection for his deceased father, while Cox seems locked in a futile bid for his unresponsive father’s approval.

One critic has said said that no matter how stupid or despicable their films’ characters may be, the Coens always leave you one to “hang your hat” on. (Perhaps literally, in the case of No Country.) He argued that Burn After Reading was different in that it had no sympathetic characters. I disagree. I think that gym manager Ted Treffon (Richard Jenkins) is Burn’s real hero. From his bittersweet interactions with Linda to his final confrontation with Cox, his character has a quiet dignity that none of the rest have—or are intended to have. They suffer by comparison—all too cruel or too clueless, or both, to relate to. While some of their suffering does arouse empathy, none of them is as sympathetic as any of No Country‘s protagonists.

I realize that one film is a drama and the other is a comedy; but Burn‘s humor falls flat in the face of its emptiness. The few laughs that No Country has are actually funnier, in my opinion.

Basically, No Country for Old Men has a heart to it that Burn After Reading lacks. . . even if that heart is broken. It has as much to do with the characters as it does with the film’s painstakingly rendered, Polaroid-toned wistfulness. In No Country, Llewellyn Moss chats with a woman by a pool, and they both agree that even when they’re watching, people never see what’s coming. At the end of Burn After Reading, with everyone either dead, deported, or bought off, two CIA operatives agree that they don’t know what the hell just happened. Unfortunately for the Coens, audiences and critics come away feeling the same way.

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.