The Abyss Gazes Into Thee: Batman, The Dark Knight, and Modern Gothic

Published on September 29th, 2008 in: Books, Comics, Halloween, Horror, Issues, Movies |By Less Lee Moore

“He who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby become a monster. And if thou gaze long into an abyss, the abyss will also gaze into thee.”

Frederick Nietzsche, Beyond Good & Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future

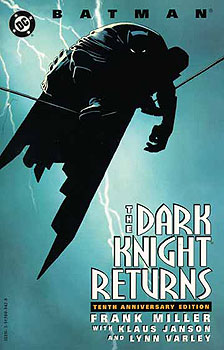

The character of Batman was first referred to as The Dark Knight in Frank Miller’s 1986 comic series Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. Referring the character as “The Dark Knight” is a twist on traditional hero and villain stereotypes, a multi-layered ironic pun. At the surface, there is reference to the “white knight,” the medieval savior of damsels in distress. Yet on a deeper level, it presents Batman as the “hero in black,” one who operates not only under the dark cover of night, but also outside of (yet in concert with) law enforcement. In this way, Batman is both a hero and a villain.

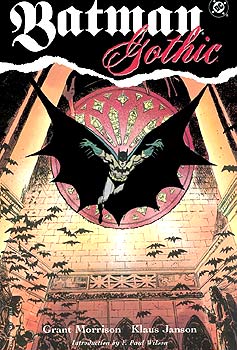

In Gothic fiction, the character of the villain-hero appears frequently. (1) Through the films of Christopher Nolan, Batman emerges as a modern Gothic villain-hero for the new millennium. The world that he inhabits is one fraught with consistent, unyielding tension and characterized by ongoing battles: between good and evil, between morality and immorality, between light and dark, but most importantly, it is a world in which humanity is divided against itself, often with horrifying consequences.

The nexus of this world is Gotham City, a variant on the word “Gothic,” which has more recently been shortened into the slang term “Goth,” and is frequently (and derisively) used to describe a subculture that developed from the 1970s punk scene. The word “Gothic” is itself borrowed from literary scholars and critics who use it to describe a trend in fiction that began around the eighteenth century.

In The Literature of Terror, one such scholar, Professor David Punter, explains that the original meaning of the term was, “literally ‘to do with the Goths’, or with the barbarian northern tribes who played so somewhat unfairly reviled a part in the collapse of the Roman empire. . . ” (2) Punter describes how during the eighteenth century, “. . . the medieval, the primitive, the wild, became invested with positive value in and for itself” because “. . . the fruits of primitivism and barbarism possessed a fire, a vigour, a sense of grandeur which was sorely needed in English culture.” (3)

Punter traces the evolution of Gothic from its inception through the twentieth century, proposing that the development of Gothic fiction may have been “. . . a form of response to the emergence of a middle-class-dominated capitalist economy. . . ” (4) The tropes of Gothic fiction have continued to persist in modern novels—as well as graphic novels and films—because capitalism itself has continued to persist. (5)

Punter’s analysis of the history and development of Gothic fiction presents the Gothic world as one that teeters on a precipice. He maintains that “. . . Gothic is located. . . at the psychological interface between the well-ordered psyche and its rebel subjects.” (6) It is this “borderland” Punter asserts, on which “fear resides.” (7)

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.