After You’ve Gone: Thoughts On Burial At Sea

Published on April 11th, 2014 in: Current Faves, Gaming, Movies, Reviews, Science Fiction |Part Two

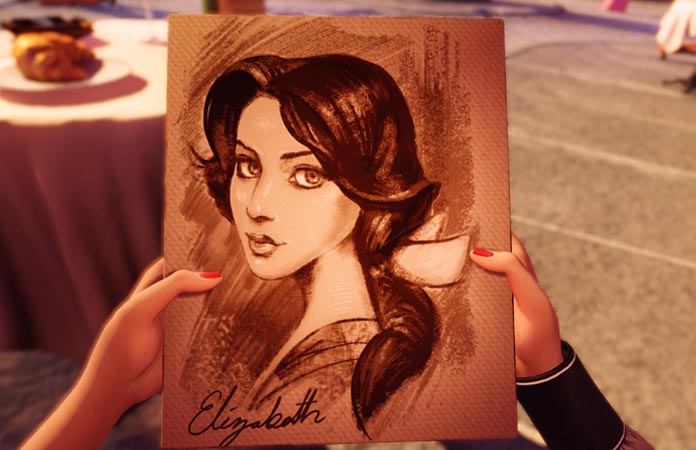

Bioshock has ended. There will probably be a sequel delivered by some inferior studio down the road, but Irrational have delivered their final word. Burial At Sea Part 2 is gorgeous and emotionally charged. It is as good as anything Irrational have done. The opening scene is an expression of the philosophy that has made these games my favorite things in any medium. You begin in a setting of otherworldly beauty, a place where Elizabeth is at her happiest. The light and feeling here go back to what Ken Levine said about the early days of work on Infinite:

“There’s a day that we were really struggling. This is before we first showed the game. We had some of the principles, some of the neo-colonial look of it, but there was something missing. I was on a run and it was in June. It was one of those perfect days. Not a cloud in the sky. The sky was this deeply saturated blue. And the sun was shining. There was a mailbox I saw. I was on my run and I had my iPhone with me. I was listening to some kind of podcast. I saw this aluminum mailbox and I saw the sun hitting the mailbox. I took my iPhone and I filmed the play of the light off the mailbox. You know you’re a game development nerd when you’re getting really excited about filming a mailbox. I brought it in to show the art guys. I took a bunch of pictures that day of flowers and the kind of saturation that a flower in June can have, in that kind of sunlight. I said, ‘This is our palette. Here’s our palette, guys, go to it!’ Then they had to sort of figure out how you make a world that’s that bold and that idealized, but also make it feel believable.”

While Ken Levine worries about how to make “endlessly replayable narrative games,” here we have one of the finest restricted moments in the series. We do not need new or different gameplay for games to tell stories that are unique. The act of being in that space is enough. The idea that video games should fundamentally be at the whim of the player is shortsighted. It misses a crucial element of what video games do better than anything else, and that is to fuse a different person and world with your own. To make the player feel compromised in a moral bother, to make that player feel responsibility for a world that is not their own, to provoke a deep sense of love for a character, that is where the real narrative potential lies. Roger Ebert was right about one thing in his wrongheaded anti-video games screed: being acted upon is the real thrill. I want the game to change me, as much as I want to change it. In its opening moments, Burial At Sea presents a scene which would not work nearly as well in a movie or a novel. That the player’s impact is limited to walking and looking is irrelevant.

Being taken along with Elizabeth as she puts the full stop on the stories of Rapture and Columbia is a thrill. It is also remarkably upsetting. First, because it closed off a meaningful part of my life and then because it is like every Bioshock story—one of difficult sacrifice. Elizabeth is still in the sunken Fontaine shopping mall, along with Atlas and the outlaw entrepreneurs who threatened to topple Andrew Ryan. This is a rich location, visually stunning, and with Irrational’s trademark level of detail. We see what school was like in Rapture, how they dealt with sex, and how the all-important bathyspheres were sold as designer cars. The game is occupied with stealth in a way Infinite certainly wasn’t and plays like a riff on Dishonoured, which is suitable given that game’s debt to Levine’s world. The pace of combat is quite different and it takes a bit to get in tune. The fear of splicers, Big Daddies, and Vox Populi is greatly heightened by your lack of combat savvy.

The stealth system comes into its own during the bathysphere showroom and repair area. Here you are free to wander around and pick out secrets from the environment. (What Elizabeth did when she first got to Rapture is a favorite!) First time through I ended up in a lavish bar with a dance floor. At first I was conservative in my approach, choosing to duck down and sneak through with a rather pleasing invisibility plasmid. Burial At Sea uses basically the same system that Rocksteady’s Arkham Asylum introduced. While not as elegant as the tagging variation used by Hideo Kojima’s team in Metal Gear Solid 5: Ground Zeroes, Irrational’s take is much better than Dishonoured. After a couple of easily located upgrades, you are given unlimited use but only when standing still. Because of the scarcity of Eve this forces different tactics, while accepting that the player is going to rely on this ability. It’s a good compromise.

Certain simple-minded, low-talent schmucks like Kirk Hamilton from Kotaku have taken the introduction of stealth as an opportunity to further condemn the level of violence in Infinite. As with everything he has written about this game, Hamilton trades the point for his moral sweater. With his moral sweater on he can look in the mirror and feel like a big boy critic. Like Chris Plante he can also, no doubt, make sure his poor sensitive companions are not exposed to nasty ideas. Let them keep thinking that Horror fans don’t exist, that Noir hasn’t given us some of the great stories of the last hundred years, and that the violence in Infinite was arbitrary. The way Burial At Sea deals with revenge and brutality would not work if the player had not first experienced the anger and sadism of Booker DeWitt.

Burial At Sea takes Elizabeth and corrupts her. She is forced to confront her capacity for evil. The Noir elements here are not superficial. Booker DeWitt was the victim of pernicious racism before he was the culprit. The actions that led every variation of Booker DeWitt to become a rotten human originated from this fear and anger. Elizabeth begins with the same desire to claim autonomy from those who would exploit her, and ends up as the mover of suffering for others. The way Elizabeth deals with enemies contrasts with those of Booker. Her culpability and eventual sacrifice is the same, though. Booker just had longer to rot in the world. This story wouldn’t have worked without first depicting Booker DeWitt as he was: a nasty, cowardly thug. It wouldn’t have worked with conversation trees. Booker DeWitt was not an agent of stealth. He reveled in his capacity for violence, even as it unsettled him, and so should the player. As in many great Noir stories, Booker made a noble sacrifice in the end, but that does not redeem his character. He was rotten down deep. It was not just his actions; it was who he was. That weakness is in Elizabeth. As Daisy Fitzroy suggested, sometimes you have to pull it up from the root.

Taken together, parts one and two of Burial At Sea are as brilliant a Rapture story as the original Bioshock. The way Irrational gather the worlds of Columbia and Rapture together gives these games a shot at the top. They explore its society in a way that lets you see why Rapture was probably a good idea at one time. As observed in part one, there are many ideological advantages that Rapture has over Columbia. One of the areas you encounter early on with Elizabeth is a sex shop. Outside the front door you watch an educational film that informs you how to draw up a written contract that ensures sexual pleasure for all involved. Inside, a large pulpy cover advertises Gender Bender. “Liberation found . . . fathoms below! Meet Chris . . . whose sexuality knows no boundaries!” There is a side to the individualism in Rapture that is intoxicating even as its cruelty is apparent.

Irrational have done extremely well in maintaining the nature of the splicers, while giving real insight for the first time into how such degenerated minds existed with those who were not so far gone. While on your way to the Bathysphere showroom, you pass a follower of Atlas who sings a song about getting a piece of the Rapture pie. Atlas is the main villain here. His place in this story will make players re-evaluate the twist in Bioshock and put most of that grumbling to bed. There is a torture scene that is as bleak as anything and sells his character as so much more than second fiddle. It helps that Karl Hanover returns as Atlas and gives a knockout performance. When he finally loses his composure, it is terrifying in a way that he never was in the original. This is partially due to the sumptuous animation. Atlas is not just a character on the radio; he is the guy who is waving an ice pick in your face. As great as Armin Shimmerman is as Andrew Ryan, Hanover places his character for the first time above that of the creator of Rapture.

When the story crosses over to Columbia, important moments in Infinite are given a new context. This is the most surprising part of Burial At Sea and allows for a whole load of secret pilfering. Appropriately this section feels very much like the opening of the hatch in the second season of Lost. In the depths of Jeremiah Fink’s outfit you discover things that you have no business discovering and it is a joy. Back in Rapture you are privy to the preparations of Atlas and his soldiers. You observe how the location of the first major strike against Andrew Ryan and the people of Rapture is decided. The Kashmir Restaurant, New Year’s Eve is where it will start and you will set it in motion.

Sometimes the prequel or concurrent story can make too big a deal out of something small. In order to give more importance to something inconsequential in the original, a character is slotted in where they don’t belong. Burial At Sea avoids that. The story is organic and unforced, owing first to the intensive work undertaken years ago to establish Rapture and then to the complexity and brilliance of Elizabeth. When we better understand the motivations and planning of Atlas and his people, it is like discovering something that already existed. Burial At Sea is overwhelmingly convincing in the details it adds to the story. With Elizabeth’s abilities and her relationship to alternate realities, she can be the cause of many things while maintaining the original game’s independence for those that care. It is the journey of her character that necessitates becoming involved in Rapture’s future. As with Atlas, the ending depicted in Bioshock is re-purposed to great effect.

Burial At Sea is as courageous as Infinite was for refusing to rest on those laurels. As a whole it can be taken as a straight up sequel. It is a daring conclusion that courts discomfort and that Lost/Prometheus confusion that is poison for some. It remains unapologetic in its Science Fiction and its use of time travel and creative interpretation of quantum mechanics. The way Bioshock Infinite and Burial At Sea examine guilt is harder edged and more compelling than anything you will find in The Last of Us, or any of those Indie shots. Its solutions are not easy. Even though you may erase a timeline, your actions will follow you.

I can’t think of any game that has explored the idea that suicide is sometimes not only desirable, but also the only moral choice. The series has always been Noir in some proportion. It is right that it should end in the purest expression of that philosophy. This is everything video games need and it is sad that more people will never realize it.

Thanks Irrational and Ken Levine.

Pages: 1 2

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.