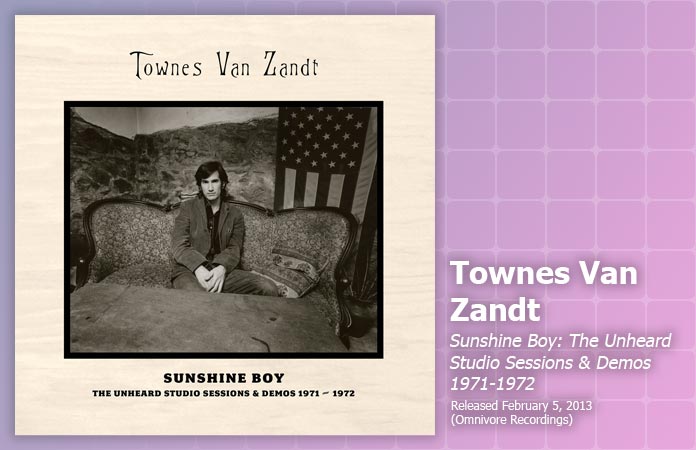

Music Review: Townes Van Zandt, Sunshine Boy: The Unheard Studio Sessions & Demos, 1971- 1972

Published on February 6th, 2013 in: Current Faves |By Cait Brennan

Townes Van Zandt burned through his short life like beads of water dancing on a hot frying pan, looking for a way out, struggling to fly, trying to take off for pretty much anywhere else. He occupied this earth for 52 years and for most of it he was in unbearable psychic pain. He self-medicated, but the treatment was worse than the disease. But from time to time, especially during the early-to-mid-1970s, he was able to transform a measure of that pain into songs of almost unparalleled beauty.

On New Year’s Day 1997, Townes slipped away, leaving us a handful of studio albums that have acquired near-legendary status. But some of those recordings are deeply flawed by poor production choices, and even the great ones have at times been hard to find. The idea of finding new Townes material after 40-plus years seemed impossible. But impossible is all in a day’s work for the good folks at Omnivore Recordings, who moved heaven and earth to bring us 28 lovingly curated tracks of never-before-heard Townes music, Sunshine Boy: The Unheard Studio Sessions & Demos 1971-72.

Townes was playing folk music in Houston when songwriter Mickey Newbury reputedly led him to Nashville and introduced him to Cowboy Jack Clement, the songwriter, producer, and engineer who first made his name working with the Million Dollar Quartet at Sun Records. Cowboy discovered Jerry Lee Lewis, wrote hits for Johnny Cash, and probably has the secrets of warp travel locked up in a safe at the Cowboy Arms Hotel. If there’s one person alive who would have appreciated Townes’s unclassifiable sound, it’s Cowboy. But it wasn’t quite a perfect fit.

Cowboy is one of the indisputable greats of 20th century music, a certifiable genius, and a personal hero of mine. Sometimes, though, the very things that are his greatest strengths—freewheeling eclecticism, unlimited imagination, proud eccentricity, innovative arrangements—have been known to lead him astray, and on Van Zandt’s debut album For The Sake Of The Song he blew enough perfume up Townes’s ass to fumigate a whorehouse. Strings, horns, harpsichords, flutes, church choirs cribbed off “MacArthur Park,” petticoats, parapets, you name it, Cowboy laid it on like Percy Dovetonsils. It got a little better on subsequent records, but if you haven’t at least fleetingly contemplated brutally murdering the off-key flute player on Cowboy’s production of “Be Here To Love Me,” you’re probably not a Townes fan.

To be fair to Cowboy, in 1968, at the very height of twee baroque pop, it was probably impossible to imagine that the best way to record a new songwriter like Townes was probably to just give up and call Alan Lomax. And you have to credit Cowboy for seeing something in a character like Townes in the first place. If he hadn’t, we’d likely never have heard some of the finest songs of the 20th century.

By the time these sessions rolled around in 1971, Cowboy Jack was occupied with producing the fine country blues singer Charlie Pride, so Poppy Records’s Kevin Eggers brought his influence to bear on the production, scaling things down and peeling back the velvet drapes. The resulting albums, High, Low And In Between and The Late Great Townes Van Zandt, are widely regarded as among his best, and these recordings mostly come from that era.

Disc one of Sunshine Boy consists of studio sessions and outtakes from Townes’s fruitful 1971-72 period. The Jimmie Rodgers tune “T for Texas” (a.k.a. “Blue Yodel #1″) starts us off, a fun song that’s never appeared on a Townes album in a studio version. Townes gets in some good yodeling and turns the lyrics more towards his natural inclinations (one suspects Rodgers’s version didn’t contain the line “I’m goin’ where the water tastes like Robitussin”).

The Bo Diddley song “Who Do You Love” made its way into a lot of Townes’s live sets over the years (including a dynamite version on Live At The Old Quarter) but didn’t appear on a Townes album until years later, on 1978’s Flyin’ Shoes, and the 1978 version sure sounds like it’s from 1978, sort of a shotgun wedding of Townes and disco. (The groom did not survive.) Thankfully, it’s all blues here, with a rock and roll punch and a wicked slide guitar that gives ol’ Elias McDaniel a pretty good run for his money.

There’s more rock and roll sensibility (and some serious acid-rock guitar licks) on “Sunshine Boy,” which heretofore only appeared in a different version as the flip side of the “If I Needed You” single. “Where I Lead Me” (later on Delta Momma Blues) appears here in a different key with a earthier feel, with great harmonica work and some subtle horns for good measure.

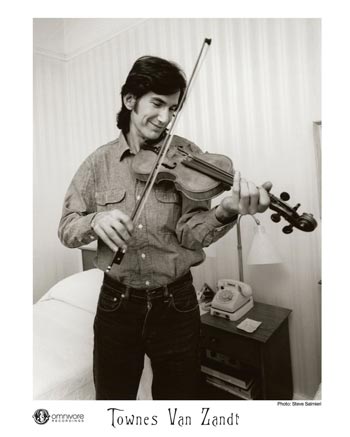

“Blue Ridge Mountains” (about the liveliest song you’re ever likely to hear about breaking your poor mother’s heart) doesn’t stray too far from the version released on High, Low And In Between, but here it’s joined by some high-spirited fiddling that takes the song back to its Carter Family roots.

“You can’t sell that stuff to me,” Townes sings on “No Deal,” a sentiment he probably didn’t express quite enough in his short life, but it’s tough to go wrong with this funny tune no matter how you slice it. The version here is a little more lackadaisical than the original, with Townes playing the storyteller to the hilt and some nice harmonies (sadly, the otherwise excellent liner notes don’t provide individual track credits, but given the challenges of even finding these tapes at all, it seems likely that information may be lost to history). Whoever you are, mystery harmony vocalist, Popshifter salutes you.

If you’ve heard one Townes Van Zandt song, and especially if you didn’t know it, it was “Pancho and Lefty,” an old-west tale that’s equal parts Cervantes and Castañeda. Emmylou Harris first covered it on her 1977 album Luxury Liner, which brought Townes a whole new audience, and when Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard made it a number one country smash in 1983, the deal was sealed. That Townes was able to survive as long as he did was probably because of the royalties this song (and “If I Needed You,” sadly unrepresented in this collection) provided. The version here is an alternate mix of the 1972 album version that mercifully removes the original’s well-intentioned but highly misguided strings and horns. Now if only Omnivore would do that to the entirety of the first few Townes records . . . especially that damned flute.

You’re entitled to be wrong, but to me, “To Live Is To Fly” is not only Townes’s best song, but maybe the best song by anybody, ever. You can keep your cold and broken hallelujahs, I’ll take “Everything is not enough, and nothing is too much to bear . . . where you’ve been is good and gone, all you keep is the getting there.” The version on High, Low And In Between is no slouch, but even with Eggers’s laudable restraint, there’s just a little too much going on. The spare, contemplative version here is gorgeous, touching on the mystic, with just Townes and a guitar until the band kicks in towards the end.

The lively “You Are Not Needed Now” is one of High, Low And In Between’s high points, but here, it almost feels a little like a Stones song, played raw, stripped of the pedal steel that adds a lush quality to the original.

Nobody, not even Townes, could improve much on “Don’t Take It Too Bad,” a waltz-time heartbreaker about the futility of trying to understand why life is so damned hard all the time. This version is more upbeat, more hopeful than the take on 1970’s Townes Van Zandt. And the rueful, bitter “Sad Cinderella” is laid (almost) bare here, with the exception of some upper-octave piano plinking that is slightly less helpful than it thinks it is.

The five-card-stud showdown “Mr. Mudd & Mr. Gold” plays very similar to the rollicking boom-chick-a-boom of the original album version, but Townes’s vocal here is more immediate, more urgent, and doubtless due to the advances in mixing since 1971, vastly more crisp.

“White Freight Liner Blues” is a rollicking travel blues with some great picking, while the feel-good “Two Hands” skips the shooting gallery and goes straight to the revival meeting. On the original, Cowboy brought the entire choir and gave ‘em all clappers and tambourines. On this more restrained (but just as upbeat) version, you’ll still get to heaven but you won’t have call Trailways to get a group rate.

“Two Hands” couldn’t have a more polar opposite than the pitch-dark “Lungs,” its scant two minutes packed to bursting with bleak imagery (“Wisdom burned upon a shelf, who’ll kill the raging cancer/Seal the river at its mouth, take the water prisoner/Fill the sky with screams and cries, bathe in fiery answers.” Presumably not a sunshine day at the Van Zandt residence).

Townes frequently covered the Rolling Stones’s “Dead Flowers,” but this is the only studio version he ever did (a live version, from Townes’s 1993 album Roadsongs, turned up in The Big Lebowski). The song, said to have been “influenced” by Gram Parsons, is all too apropos for Townes, being as the tune delves deep into heroin addiction, the dead flowers in question reputedly being of the, ahem, injectable variety. We’ll overlook the fact that Townes was on Poppy Records at the time, but what we can’t overlook is that Townes’s “Dead Flowers” is vastly better than then Stones version. Jagger’s disaffected, mocking vocal makes no effort to conceal his distaste for country-influenced material and for that matter, country fans (that guh-huh “yokel” accent should have earned Mick a good sock in the jaw from Merle Haggard a long, long time ago). On this version and the one that follows on the Demos disc, Townes truly makes the song his own.

There’s a reason many Townes fans regard the unassailably pure Live At The Old Quarter as an almost holy document. Stripped of everything but Townes himself, his songs stand on their own merits, played with tremendous feeling and soul in front of a rapt audience. For Old Quarter fans, then, this second disc of demos is pretty much the Holy Grail. Here over thirteen tracks is essentially just Townes Van Zandt and a guitar, his warm and unaffected voice as immediate as if he was here in the room, singing songs like “To Live Is To Fly” for one of the first times ever. Several of the tunes from disc one are represented here, as well as gems like the Townes/Guy Clark composition “Heavenly Houseboat Blues” and the very early, raw “Tower Song.” There’s some great stuff here including nascent versions of “Greensboro Woman” and “Highway Kind.” The great Muhammad Ali-meets-Lightnin’ Hopkins tune “Diamond Heel Blues” has never turned up in a studio version, and neither has the wonderful “Old Paint,” (a.k.a. “I Ride an Old Paint”), a 19th century cowboy folk song that Townes really seems to enjoy playing. A lovely little untitled snippet of Townes playing guitar ends the set on a sweet note.

Omnivore Records’s Cheryl Pawelski deserves the musical equivalent of the Nobel Prize for pulling this album together. Starting back in her days at Capitol, the Grammy-nominated archivist and producer went on a 20-year personal quest battling through a red-tape nightmare of defunct labels, bankruptcies, mergers, and god only knows what else in order to bring this material to the public for the first time. Maybe it’s just another day at the office for Omnivore Recordings, whose tireless efforts in the service of great music have brought forth unconscionably neglected material from Bert Jansch, Sam Phillips, Jellyfish, the Motels, the Knack, Richard Thompson, Big Star, and so many more. Every cynical nitwit you’ve ever heard badmouth record labels should be boiled in their own lattes while labels like Omnivore exist in the world. Pawelski is a hero to music and Townes fans in particular ought to erect a statue.

In later years Townes revisted these songs many times, for both artistic and commercial reasons. Any songwriter knows how songs change and grow and reveal themselves to you slowly over time. Odd mistakes suddenly seem like divine providence, and besides, Townes was never quite satisfied with the earlier versions. But Townes was never the best judge of his own gifts, and these recordings would be tough to equal under the best of circumstances. Here, in these holy moments stolen from an impossibly troubled life, stripped of needless flourishes, and finally given the loving attention he always deserved, Townes Van Zandt is as close to perfection as this broken world allows.

Sunshine Boy was released through Omnivore Recordings on February 5 and is available to order directly from their website.

One Response to “Music Review: Townes Van Zandt, Sunshine Boy: The Unheard Studio Sessions & Demos, 1971- 1972”

November 27th, 2016 at 2:32 pm

Excellent assessment of this collection and of Townes’ work, in general. I personally agree wholeheartedly with the “To Live is to Fly” > “Hallelujah” opinion, although I love the work of the late, great Mr. Cohen, too.

One minor quibble, though: “Heavenly Houseboat Blues” was co-written by Townes and Susanna Clark, not Guy.

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.