TV is Dead, Long Live TV: I Welcome Netflix As Our New Television Overlords

Published on February 1st, 2013 in: Streaming, TV, TV Is Dead Long Live TV |

The author’s Netflix home screen. Our new media overlords know what my family wants to watch a surprising amount of the time.

With House of Cards premiering February 1 on Netflix, it’s time to acknowledge our new media overlords. While I have yet to see the new series, I have a strong suspicion I’ll like it—Kevin Spacey was born to play to the Devil, and television loves an actor that chews scenery. As long as the writing is solid, with Spacey in the lead and Robin Wright as his dance partner, they could be acting with no sets and wearing clothes by Hanes sweat suit division and I’d still watch. Investors agree with me; Netflix stock shot up 42 percent in the last week, but exactly why the stock made such a dramatic jump is a reflection of the struggle between old and new media, and involves the death of linear TV and the complex copyright struggles that tangle all visual media distribution.

I have a friend who used to make images of the Devil with pictures of Kevin Spacey.

Something about him just gives me the creeps, and good on this show’s producers for spotting his evil abilities.

In 2011, Netflix stock was over $300 per share, and for good reason. In the United States, cable television companies have successfully prevented any attempt to provide customers with a la carte pay television options. Stuck with cable bills each month well over $100, television viewers have grown resentful that they must pay for hundreds of channels they don’t watch in order to access the few that they want. Despite the support of the FCC, lobbyists from both cable and religious organizations defeated the very popular Family and Consumer Choice Act of 2007 that would have made mandatory bundling of cable illegal.* With ever-growing libraries of content, Internet companies such as Netflix, Hulu, and hundreds of other providers are affordable entertainment options that offer choice programming that consumers can control themselves.

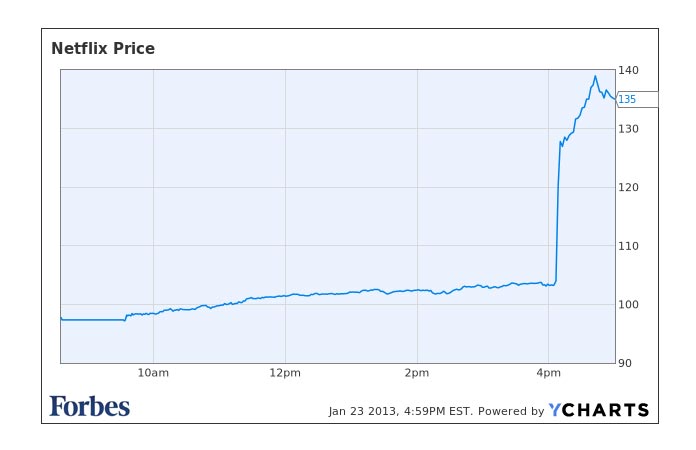

But back to that stock price—why did Netflix fall from a high of $300 per share to less than $100 per share at certain times in a 12-month period? Why does the stock go up and down so often? Why don’t investors love our new media overlords more?

Some of the recent Netflix stock madness.

The answer in part is that they do, but that they don’t understand media. Additionally, placing a value on art has always been tricky. As I type this, NBC/Comcast stock is trading at a little over $38 per share while Netflix trades at over $160. I use NBC/Comcast for comparison not only because it owns both cable and broadcast channels, but also because the last season of 30 Rock has exactly addressed these same issues.

In the episode “A Goon’s Deed In A Weary World” (which you can watch on Hulu or buy on iTunes), the characters discuss stripping NBC for parts and turning it into a Forever 21 store. I’d hate to see that happen, but if it did, shows like Parks and Recreation and Community will just have to move to Netflix- or Hulu-type distribution channels. Look for this to happen next year if the re-launch of Arrested Development makes lots of money on Netflix. Again, the folks at Netflix are our new television overlords; it’s impossible to write about any changes in current TV production without referencing them.

But how much are they worth? Well, that depends in large part on how much the licensing fees from movie studios and other content rights holders charge Netflix for their content. Disney charges Netflix $300 million per year for its library, and that’s the top. I’d guess that smaller independent films—let’s use The Rock-afire Explosion as an example—get just a few thousand dollars per year, or a one-time payment. Netflix must have enough paid subscriptions to pay back their licensing agreements and their overhead in order to make a profit. They are also in danger every time a licensing agreement expires, as companies such as Starz might decide to pursue other distribution channels. Even then, it would seem like Netflix is a solid investment, as they are clearly on the path to producing original content with more simplified copyright issues.

A company is only as solid as its management, however, and they sometimes make missteps; large, popular chunks of the Netflix library are only available on DVD as some companies refuse to license streaming. HBO is the biggest offender here, locking off documentaries and series like True Blood. Some of the disc-only options are just legacy pieces of older libraries, where the cost and effort to negotiate these newfangled streaming fees just hasn’t been a priority for Netflix or the rights holders. Whatever the case, in September of 2011 Netflix decided that it would be easier to separate the streaming and disc sides of its business, likely because it would save lots of money in lawyer’s fees. Famously, this did not go over well, and a lack of confidence in Netflix management has dogged the company since.

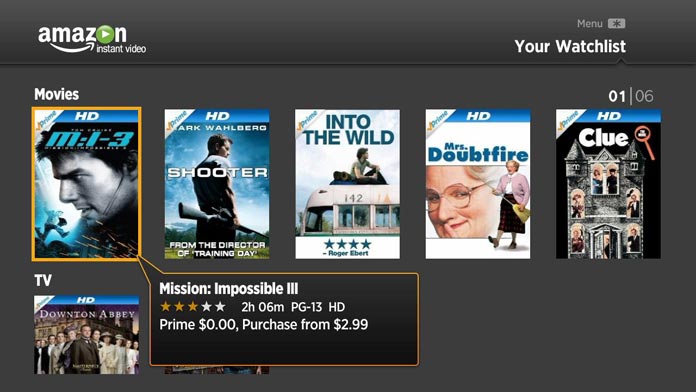

Add to the lack of management confidence Wall Street’s groping to understand social media, and you start to get a better idea of why Netflix stock experiences dramatic fluctuations. When the CEO of Netflix maybe accidentally violated stock exchange rules by posting viewing rates on Facebook, the stock took a dive, ignoring the fact that this Facebook posting did nothing but please hard core Netflix fans—the ones driving profits. Just a few weeks ago, an analyst predicted Netflix earnings would be down, on the mistaken idea that Red box instant and Amazon Prime will take off. Anyone who actually streams video could have patiently explained to the analyst why Amazon Prime isn’t really a contender (you essentially have to buy many videos) and that the Redbox library is too anemic to really compete.

In short: Wall Street doesn’t understand how to price Netflix because Wall Street doesn’t watch TV. The best thing Netflix could do for itself is ignore Wall Street altogether, and concentrate on what it does best: providing an interesting and constantly updated library of content for users.

Even if you have a paid subscription, you must pay for many movies on Amazon instant. This screenshot shows a rental for older films, but newer releases can cost as much as $12.

* If you’re wondering why religious organizations are involved with this, it has to do with televangelism. Currently cable companies must provide access to local broadcasters by law, so many churches have invested heavily in local broadcast stations as televangelism is a proven donation driver, and with a la carte, well . . . how many people would really choose to pay for a church channel? Not many. Weirdly, this is why you must pay for an entire basic cable package in order to then pay extra for HBO just because you want to watch that one show that’s only on for 20 episodes. Because televangelists need to be able to get into your home 24 hours a day to tell you about their version of Jesus and ask you for money to support their activities, including campaigning against a free market. No one ever accused the United States of being rational where money and religion are involved.

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.