Basquiat Goes To The Cinema

Published on August 20th, 2012 in: Art, Documentaries, Movie Reviews, Movies, Reviews |

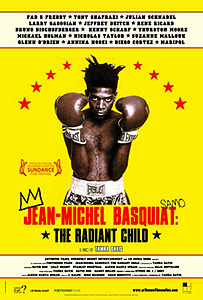

Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child, 2010

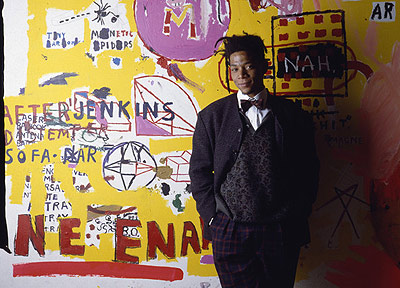

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s life seems all but made for the silver screen. The art world star lived fast. During his 27 years on the planet, he created a complex, engaging body of work. In addition to his solo paintings, he collaborated with Andy Warhol and formed the No Wave band Gray. He died young as the result of self-destructive habits. And he left a good-looking corpse. The half-life of flickering 16mm and unforgiving video reveals a young man with the sulky charisma of a 1950s screen idol.

About a decade after Basquiat’s death, he began surfacing in the movies. His life has the potential for either a brilliant big-screen epic in the style of Lust for Life or a misdirected attempt at catching lightning in a bottle. How have the different films about Jean-Paul Basquiat stacked up?

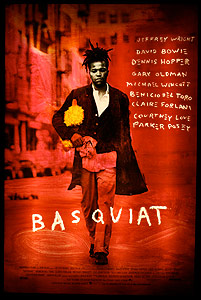

Julian Schnabel’s biopic, the simply-titled Basquiat, opened in cinemas in the fall of 1996. According to a recent interview, Schnabel—a legendary painter and bon vivant—took on this project after being interviewed for a competing feature on the artist. As a contemporary of Basquiat’s, Schnabel wanted to make sure he did right by his peer and fellow traveler.

While Schnabel’s motives were pure, Basquiat is a strangely unsatisfying affair. This biopic follows the “stations of the cross” format favored by directors of films about troubled artists. While he doesn’t yoke Basquiat’s creative impulse to drug addiction or a troubled family, he does foreground those aspects of Jean-Michel’s life. The film opens on Basquiat splitting an eight-ball with his roommate after visiting his mother at a mental hospital. While we see Basquiat working on his canvases, Schnabel devotes more time to the vagaries of the commerce-driven ’80s art scene in New York. Further, we don’t see any depiction of Basquiat’s very productive time in Los Angeles, or the macabre gallery show that became his last.

The film has a lush, Miramax-happy tone at odds with some of the clumsy mistakes one sees in directorial debut features. Schnabel’s haphazard employment of fade-outs throws off the film’s pacing. The on-the-nose soundtrack selections (The Modern Lovers’ “Girlfriend” when Jean-Michel first meets his love interest Gina; “White Lines” during the aforementioned drug scene) seem destined to sell CDs. While Schnabel shied from indulging ’80s nostalgia with a retro-tacky palette, the washed-out colors and exteriors clean of graffiti—combined with Claire Forlani’s post-grunge wardrobe—situates the film in the Sundance era.

Jeffrey Wright landed his first leading role as Jean-Michel Basquiat. While he’s shown an offhand charisma and a knowing charm in his later work, he plays the painter with an anesthetized sense of detachment. His Jean-Michel is a rube from the outer boroughs who wants to be famous, and who seems to not know his effect on those around him. This laconic quality serves him well in scenes where Basquiat addresses the racism prevalent in the art world. For example, the interview with a well-intentioned, privilege-blinded white journalist (played by Christopher Walken) could have come off as a lecture, were it not for Wright’s deadpan line readings. However, the laid-back approach doesn’t work for the rest of the film.

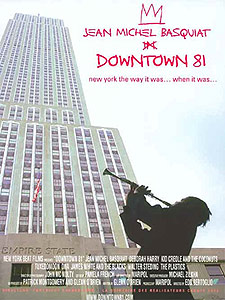

Schnabel elided over Basquiat’s sole appearance as an actor, in the film Downtown 81. Glenn O’Brien, who created the punk public access show TV Party, produced this low-budget fairy tale set on the Lower East Side. The producers—the family who owned disco denim empire Fiorucci—ran out of money before the film was completed, and the rushes disappeared not long after. In the wake of Basquiat’s modest box office success and ubiquitous afterlife on basic cable, O’Brien and his cohort Maripol located and edited the work print into a feature-length movie. In the absence of the original dialogue track they re-recorded the entire soundtrack, with Saul Williams assaying Basquiat’s role as “Himself.”

When I caught this in its original run, the re-recorded soundtrack took me out of the film. In a few scenes, the lip movements don’t quite match up to the spoken words, which give it the appearance of a Godzilla movie. Seeing it a decade later helped me to better appreciate what I was watching. The exteriors shot in bombed-out areas of the Lower East Side have a grimly comic quality, since most of the real estate built on those areas commands a million-dollar price tag in post-millennial currency. On the flip side, the footage of ZE Records recording artists Kid Creole and the Coconuts and James Chance and the Contortions—playing at the legendary Mudd Club and Peppermint Lounge, respectively—are electrifying performances and may cause viewers to experience uncontrollable nostalgia. Though the subplot involving The Felons eventually pays off, Chris Stein’s lengthy monologue about trying to get signed drags the film to a screeching halt.

At the center of the film is Jean-Michel Basquiat, going about a magical version of a typical day in his life. He gets evicted from his apartment and just needs a place to stay while he gets his back rent, but he’s as invested in making art and meeting beautiful women as he is in paying off his landlord. Along the way he makes some unusual tags—including a multiple-choice graffiti bomb on some scaffolding—and catches some punk music. Jean-Michel’s denouement has both a whimsical side (one that involves Debbie Harry as the best fairy godmother ever), and an aspect that I found slightly cynical. (This might say more about me than about the actual closing, though.) Basquiat’s presence at times seems like a reactive one. He regards the punk and new wave scenes in New York with an arched eyebrow and a smirk, as though he can’t believe the spectacle unfolding before him and doesn’t know his place in it.

After seeing Jeffrey Wright play Basquiat, and after seeing Basquiat himself play a role inspired by his experiences, viewers might want to see the real Jean-Michel Basquiat. Contemporary B-movie director Tamra Davis has you covered. As a film student at UCLA, Davis conducted one of the few video interviews with the artist.

Her documentary The Radiant Child contextualizes Basquiat’s work in the NYC art world, from a racial perspective, and in the history of the Basquiat family. After seeing Basquiat, learning the real story behind some of the characters and events was fascinating. Julian Schnabel’s presence in the film allows us to see a more complex, competitive variation on the brotherly friendship portrayed in the biopic. The “real” version of the interview Basquiat did for the TV crew is also much funnier than its staged counterpart.

However, the star of the show is Jean-Michel Basquiat. He appears neither as the go-go salesman that many of his art-world peers were, nor as the doped-up bridge and tunnel denizen of Schnabel’s depiction. The Basquiat that emerges in Davis’s portrait is a ruminative artist who takes his time choosing the right words for his interlocutor’s questions. His thoughtful, ethereal presence made him more of a human presence for me, and reminded me of some people I know.

Unlike the other films, The Radiant Child puts Basquiat’s presence front and center. Various interview subjects speak to a fortuitous gift of Grey’s Anatomy as the spark that lit his interest in art and informed his chaotic, anatomically inspired canvases. His tendency towards competition among other artists and his love of hard bop are also paralleled in his work. While Tamra Davis obviously has a great love for her subject, she portrays him in a multifaceted way and does look at his less pleasant sides. Her subjective take on Basquiat is much welcomed.

Fans of Basquiat’s paintings who want to learn more about the painter would be wise to start backwards, with Davis’s documentary, and work towards Downtown 81 and eventually Basquiat.

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.