Thoughts On: The Band, MUSIC FROM BIG PINK

Published on June 18th, 2012 in: Music, Music Reviews, Retrovirus, Reviews |By Paul Casey

Part one in a continuing series on THE BAND’s discography.

To read the whole series, go here.

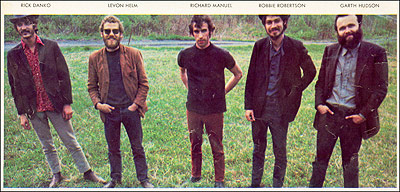

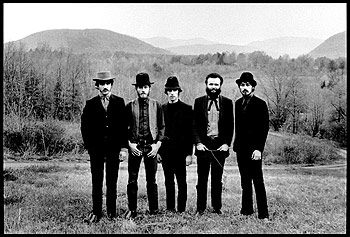

THE BAND is Rick Danko, Levon Helm, Garth Hudson, Richard Manuel and Robbie Robertson. In common chatter, they are known first for being Bob Dylan’s backing band during the most combative and divisive tour of his career, and second, for convincing Martin Scorsese to film their last concert as The Last Waltz. Those who are fixated on “classic rock” may know them for the issues that existed between the members of the group, and how Robbie was a preening ego-fuck who took glory for himself alone in the last gasps of their existence.

Like The Eagles, and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, THE BAND was home to acrimony over songwriting credits, royalties and differing philosophies. It was also home to five multi-instrumentalists, four of whom sang and wrote material. Unlike those supergroups, THE BAND did not come after the fact. They were a supergroup because of their combined talent, not their individual fame. This does not make them superior to those bands, but it is significant to the changing dynamics which resulted in The Last Waltz and their untimely end. To understand why THE BAND are so respected and influential is just to hear their music.

Music From Big Pink is when THE BAND stopped being The Hawks, The Honkies, The Crackers or Bob Dylan’s backing band. To understand where Music From Big Pink is coming from, it is necessary to understand The Basement Tapes. Not the double LP released in 1975—which will be covered at a later point—but the series of recordings made by Dylan, Danko, Hudson, Manuel, Robertson, and very near the end of the sessions, Levon Helm.

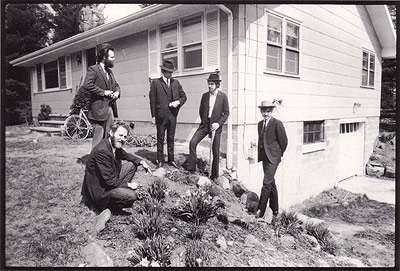

The Basement Tapes were recorded in 1967, mostly in the basement of THE BAND’s Woodstock house, Big Pink. They followed the dismantling of Dylan’s cold, amphetamine-driven Highway 61/Blonde on Blonde persona. They also followed a serious motorcycle accident that provided the opportunity for Dylan to re-evaluate where things stood. The sessions comprised of some covers—”Folsom Prison Blues,” “The Auld Triangle,” “Joshua Gone Barbados,” et al—and an outpouring of new material. This new material was steeped in the same traditional music that had so entranced young Bob, but was filtered through absurd humor, the lyrical complexity of Blonde on Blonde and the evasive narrator of John Wesley Harding.

Three of the songs recorded during The Basement Tapes would be re-recorded by THE BAND for their debut album. The opening “Tears of Rage,” co-written by Dylan and Richard Manuel; “This Wheel’s On Fire,” co-written by Dylan and Rick Danko; and “I Shall Be Released,” which Manuel would make his own long before Dylan recorded it for Greatest Hits Volume 2. The Basement Tapes were more significant to how THE BAND’s first significant outing as recording artists was shaped, than simply being the starting point of some of their most famous songs. The sessions’ philosophy of united creation, discarding unhelpful egos and petty squabbles would motivate THE BAND’s best work.

When George Harrison returned to The Beatles for the Let It Be sessions, the cohesive unit of THE BAND, along with the ego-free collaborations they had with Dylan, made the troubles of the most famous group in the world harder to tolerate.

“I’d just spent like the last six months producing an album of this fellow Jackie Lomax, and hanging out with Bob Dylan and THE BAND in Woodstock, and having a great time, and for me to come back into the ‘Winter of Discontent’ with The Beatles in Twickenham was very unhealthy and unhappy.”

—The Beatles Anthology documentary

Music From Big Pink, like The Basement Tapes, is steeped in a constructed—though oddly not affected—American history. Old time, Dustbowl Farmer. Gallows justice. Although not as obvious as it would be on their second LP—The Band—this would be the defining aesthetic character of THE BAND. This was not exactly recalling an older time, it was creating an alternate present in which to live and make music. Levon Helm would remark in the official documentary on THE BAND—the one without the involvement of Robbie Robertson, take that Scorsese—that there was a deliberate attempt to avoid the hippie/flower power trappings of the 1960s. In spite of their divergent old timey aesthetic—which they knowingly cultivated through the photographs of Elliott Landy—Music From Big Pink arrived in the right decade.

The artistic commune of the Big Pink house in Woodstock, New York, is given timeless form in the overlapping, trade-off vocals. “The Weight,” THE BAND’s most celebrated song—besides perhaps “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down”—and its chorus spoke truly to the purest hopes of the 1960s. “Take a load off Fannie, take a load for free/Take a load off Fannie, and you put the load right on me.” I won’t let you fall brother, I’ll hold you up. Rick Danko’s verse is perhaps the single greatest thing THE BAND ever did. Everyone needs to do the Chester face.

Music From Big Pink is from a collective perspective. Even when Richard Manuel paints a despairing figure in “Lonesome Suzie” or Rick Danko mourns a lover in “Long Black Veil,” the group is right there to give comfort. “Long Black Veil” also recalls the respect given to the musical past that formed these five men. When you make Johnny Cash look like he has no business singing a song, you know you have done right.

Robbie Robertson also remarked in the Classic Albums episode on the making of The Band, that there was an attempt on his part to eschew the tendency for indulgent soloing, in favor of the impact of the song. There would be time for instrumental virtuosity—especially from Garth Hudson—but THE BAND lived and died by the power of the songs. For as powerful and successful as their second, self-titled LP would be, Music From Big Pink has an eclecticism in songwriting that would remain unmatched through their career together.

Not only does the album benefit greatly from having the presence of Bob Dylan on three of its tracks, it also has contributions from Rick Danko and Levon Helm—on the lyrics for “Chest Fever”—and most importantly from Richard Manuel. Manuel’s work here suggested an entirely different tonal direction for the group. The mystic, picture forming beauty of “In a Station” or the already mentioned “Lonesome Suzie” do not precisely fit the American Roots character the group would adopt so fiercely in the following years. When Manuel wails as he does on “Tears of Rage” he sets the mood, a unique character that such fellows as Eric Clapton singled out as being what drew them to THE BAND’s work. Lonely, fragile, doomed. No-one needed THE BAND like Richard Manuel. And THE BAND needed Richard Manuel.

When Helm was angered at the way The Last Waltz depicted Robbie Robertson as the leader of THE BAND, it was the lack of focus on Manuel which caused the most upset. Manuel was as significant a songwriting influence on THE BAND in their early years as anyone, and when he moved into the background, spurred by fierce depression and a bad drug habit, the group’s output became the sole responsibility of Robbie Robertson. To downplay the importance of Robertson though, would be terribly foolish.

As with Don Henley, Stephen Stills, or Paul McCartney, the pull for revisionist chatter that tears down accepted knowledge, ends up constructing an equally blinkered, misguided need for absolute truth. Robbie Robertson was an incredible songwriter, and an undervalued singer when he got the chance—check out his crackly shout on “To Kingdom Come.” Music From Big Pink is the only album in the history of THE BAND—excluding the cover album Moondog Matinee—which does not feature a majority of his compositions. The four songs that he is credited for include the aforementioned “To Kingdom Come,” the winding narrative of “The Weight,” the out of time beauty of “Caledonia Mission”—perfected on the live album Rock of Ages—and the straight up, fever dream rock of “Chest Fever.” This song would be a concert stand out, with Garth Hudson performing improvised organ intros, titled “The Genetic Method.” According to Helm, he and Richard improvised the lyrics during the session. Something which neither received credit or royalties; another sore point between Helm and Robertson.

When The Beatles broke up, Rolling Stone interviewed John Lennon and he took a lengthy shit on Paul McCartney. One of Lennon’s major beefs was with how McCartney directed the group in its later years. A lot of the conceptual elements were of Paul’s making—Sgt. Pepper, Let It Be—and this rankled Lennon. To McCartney though, he was simply pursuing the best ideas he could. If Lennon did not want to adequately contribute to the upkeep of the group, why not step in? Robbie Robertson was put in much the same position in THE BAND. It was not that Robertson was averse to the others taking up the mantle of songwriter, it was that they either were not interested, or not capable of doing so. In Rob Bowman’s liner notes to the remastered Stage Fright, Robertson mourns the loss of Manuel as a collaborator.

“I did everything. I wrote with him, I begged him, I pleaded with him, I offered to become partners with him in songwriting. I hounded (all the guys) to death about writing. To me it was just hard work. If it doesn’t come, well, you just got to work harder, you’ve got to make it come. Richard would say, ‘Well, I am trying.’ And, I’m sure he was. Who knows what it is, why somebody does it and somebody doesn’t. I just assumed it would continue. When were going to do our second album, there was nothing coming. So, when I’d be working on something, I’d pull him into it and make him work on the song with me just to get him in the mood or to give him a taste for this, thinking then he’ll go on to follow it up. But, he didn’t. My theory is some people have one song in them, some people have five, some people have a hundred.”

On Music From Big Pink, Robertson didn’t need to push anyone. Everyone is united on these recordings. The friendships are intact and the philosophy established during The Basement Tapes and years on the road, is still conducive to creation. It is, in many ways, the most interesting record in their catalogue, and the most vital. It is the product of five guys who loved each other and were made to make music together.

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.