In Defense Of Lost

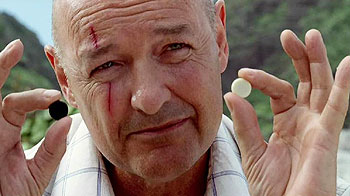

Published on May 30th, 2011 in: Climb Onto The Nearest Star, Issues, Science Fiction, TV |Locke (Terry O’Quinn), in particular, will go down as one of the great characters in modern science fiction and fantasy. Viewing his arc is proof of two important things: first, that the show is far more considered and planned, in its central story, than is claimed by its detractors; and second, that the show has a far darker edge than is appreciated.

Ultimately, Locke was a sucker. His faith in his destiny was misplaced. He is one of the only characters in the show whose flashbacks are not immediately relatable to his on-Island adventures. Sure, “Walkabout” (Season 1, Episode 4) establishes for the first time one of the key realities about the Island—that it is a place of miracles and the altering of the natural order. Look though, at his second episode, “Deus Ex Machina” (Season 1, Episode 19), and see how he is established as someone who can be conned, because of his need to have something to believe in.

In this episode, it is the belief that someone, somewhere, loves him and cares he exists. His kidney is taken from him by his own father. And just as Locke’s desire for a father takes his only real love away from him (his partner Helen, wonderfully played by the versatile Katey Sagal), it eventually sees him dead, manipulated by Ben and the Black Smoke. (If Locke is the best character in Lost, Ben is a close second.)

Locke is seen as weak through the course of the show, but the viewer never doubts that he knows what he is doing. It is a wonderful turn in his character, in the fourth and fifth seasons, when he finally thinks he has reached the mountaintop and that he understands his purpose. Yet, he is not acting for the forces he thinks. Locke’s need for a father never left him. For that, he dies.

As with his connection to Sawyer (Josh Holloway), whose episodes examined in detail the nature of the con and its relation to the show, Locke’s story plays out at length. The eventual convergence of these two stories in “The Brig” (Season 3, Episode 19), where Locke, unable to rid himself of the evil of Anthony Cooper, calls on Sawyer to take on his burden, is surely one of Lost’s creative peaks. While otherwise good characters faltered, with inconsistent motivations or a paucity of material, Locke never did. He was the pulse of the creative desires of the producers and writers.

His connection to the central mythological and thematic ideas around which the show is based is surely a reason for this. From his first meeting with the Black Smoke—as terrifying and magical a creation as Twin Peaks’ Bob—to his descent into the Hatch in perhaps the show’s greatest season opener, “Man of Science, Man of Faith” (Season 2), Locke’s progress was that of the audience. When he looked upon the Hatch door’s map in “Lockdown” (Season 2, Episode 17), we wanted to know its secrets just as much as he did. (As an aside, a look at it will tell you how far ahead the writers were preparing, in terms of plot.)

And how about that plot? For a mainstream, network television show to have been so tightfisted with its information, for so long, is simply incredible. A look at the demise of the seminal Twin Peaks shows it to be dishearteningly cowardly in the face of public pressure. And to the inane questions of “But what does it mean?” or more appropriately, “What are the polar bears doing there?” the inability of a certain section of the audience to comprehend straightforward elements of Lost, as they had with Twin Peaks, is surely one reason for their issues with the time travel, apparitions, and possession of body and spirit.

I am not here to suggest that everything was prepared beforehand. That would be insane to expect, of real people making a real television show. I do think that the central story, which JJ Abrams and Damon Lindelof (and then Carlton Cuse) wanted to tell, was pretty well thought out, and that no major issue was raised by the writers without a good idea of where it was going. That is not important to me, anyway. All that matters is that the way the story did play out, and that it worked.

They waited two years before showing the Black Smoke. They waited six years before they revealed its nature. Planned or not—and I believe it was—that takes confidence and bravery. A bravery which it pains me to admit David Lynch and Mark Frost did not possess with Twin Peaks.

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.