Portrait of a Reputation: The Woodmans

Published on March 30th, 2011 in: Art, Back Off Man I'm A Feminist, Documentaries, Feminism, Issues |By Chelsea Spear

The early months of 2011 find artist Francesca Woodman in the spotlight. After numerous solo shows throughout the United States and Europe, the photographer will be the subject of a career retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Her work changes hands for hundreds of dollars. Established photographers like Cindy Sherman and Photoshop illustrators such as Rosie Hardy cite Woodman’s ethereal self-portraits as a key influence.

Attracting such a rapt audience for one’s body of work is the desire of many a photographer, but Woodman did not live to find her followers. Thirty years ago, in the wake of many professional setbacks and the failure of an intense romance, Woodman committed suicide. How has her family—professional artists, all—dealt with Woodman’s demise, and with the mounting critical and popular interest in her work? Documentarian C. Scott Willis looks at Woodman’s life and death and the survival of her family in his first feature-length documentary, The Woodmans.

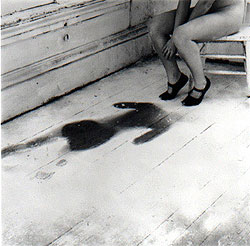

Francesca Woodman

Untitled, Rhode Island, 1976

Throughout the film, Willis foregrounds George and Betty Woodman’s devotion to their work. He cuts between Betty’s work on a ceramic sculpture for the US Consulate in China and tales of her early romance with her husband. Both of them speak of their deep commitment to making art. As Betty says early in the film, “I couldn’t live with someone who didn’t give making art the same importance I give it. I would just hate them.” George’s description of how the couple impressed the importance of creative activity upon their children—going so far as to discourage Francesca and her brother George from participating in hobbies—helps to establish the seriousness with which Francesca would later pursue her work.

For admirers of her photography, the documentary’s second act sheds greater light on how Francesca approached her work. Much of this deglamorizes the myths that have formed around her eerier nude self-portraits. Sloan Rankin, a college friend of the photographer’s, describes the mundane inspiration that went into some of her most notable work. (A toppled truck that had spilled flour across the freeway by her workspace inspired Francesca to dust her studio with flour and take pictures in the impressions the flour left beneath her.) An Italian model with whom Woodman worked spoke of the way Francesca would sketch out the portraits she took, to give herself an idea of camera placement and composition.

While Willis and his interview subjects lavish attention on Francesca’s work, one absence is felt deeply: that of Francesca’s college boyfriend, Benjamin Moore. His role in Francesca’s life is one of some controversy within the film; Rankin speaks of him as an equal who provided Francesca with stability, even as their relationship faltered, while Betty mentions him with something resembling contempt. Francesca’s diary entries from this era seem to almost hint at the possibility of an abusive quality to their relationship, from which both Rankin and Betty shy away.

After exhibiting what Rankin described as a “rock star quality” and ambition at Rhode Island School Of Design, Francesca didn’t achieve success as quickly as one might expect when she moved to Manhattan. While her work was recognized by her peers (an artist’s agent describes her as “one of the greatest photographers of the 20th century”), her work was never picked up by a gallery, and her attempt at breaking into fashion photography faltered. After a particularly bad week in which her bike was stolen and she was turned down for a grant from the NEA, Francesca did the unthinkable.

If one can relate this kind of material to audiences in a tasteful way, Willis does so. While his interview with George is almost clinical in its distance, a memory from a childhood friend who called Betty and was struck dumb by the tragedy brings it home in a more palpable way.

How does a family recuperate from this kind of heartbreak? Betty speaks of giving up art for years, and only returning to ceramics with beautiful—instead of useful—objects, stating that these decorative sculptures make viewers happy. While George’s presence throughout the film is one of an avuncular elder, his method for dealing with his daughter’s death proves to be rather shocking.

The Woodmans marks the first time George and Betty have spoken at length about their daughter’s life and death. C. Scott Willis takes a tender approach and gives them the time and space they need to discuss Francesca’s influence on the world of modern photography. His PBS-worthy interviews and intercutting are livened with a playful visual approach worthy of Francesca herself. The use of shrine-like imagery in the film’s title sequence and Willis’s touches of primary colors, combined with visuals from Francesca’s video work, give the film a visually engaging approach.

The Woodmans will be screening at the International Film Series at Colorado University in Boulder on April 9. For more on the film and future screening dates, please visit the official website.

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.