Inception‘s Deception

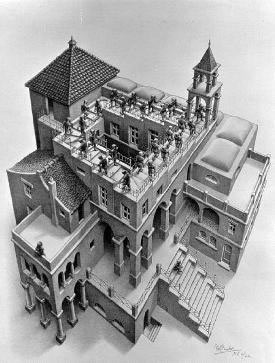

Published on July 30th, 2010 in: Movie Reviews, Movies, Reviews, Science Fiction |“Yet both directions, though not without meaning, are equally useless.”

—M.C. Escher on his lithograph Ascending and Descending, 1960

Filmmaker Christopher Nolan has only been making features for a little over a decade, but he has already established a singular style, both visually and thematically. Nolan deals in dreams and memories, in morality and duality. His latest film, Inception, is no exception to this trend.

Inception‘s fantastic score, by Nolan stalwart, Hans Zimmer, is immediately captivating and emotionally engaging. And like all of Nolan’s films, the camera work in Inception is stunning, at times literally breathtaking, courtesy of Director of Photography Wally Pfister. Viewers are treated to both sweeping vistas and claustrophobic tunnels.

M.C. Escher, Ascending and Descending, © 1960

The design and plot structure of Inception both reveal a different series of tunnels, or more precisely, layers of them. Like he did with The Dark Knight, Nolan manages to sustain the suspense at all times, lurking just behind the audience’s consciousness—even when the action on the screen is low-key—so that the two-hours-plus running time feels a lot shorter, a reflection on the difference between real time and dream time that is such an integral part of the film itself.

In Nolan’s 2006 film adaptation of the novel The Prestige, competing magicians try to outwit each other with schemes and deceptions. There are similar machinations in Inception, but here corporate espionage is carried out through controlled dreaming experiments known as “extractions.” This process is but one piece of the film’s puzzle, however. Just as in Nolan’s film Memento (2000), there is an emotional and deeply personal schism that can only be healed through the exploration of memories (or loss thereof).

If Nolan is derivative of anything, it’s of himself, although one suspects that like many other great filmmakers, he is compelled to continually explore the recesses of his own psyche in an attempt to unravel some nagging, unresolved issues.

A film like Inception is so unique and complex that is it often compared to other films with similarly labyrinthine structures such as The Matrix. Although there are some crossovers between the two (false or virtual realities, specific machines which aid in the process), what The Matrix lacks is an emotional core or anchor that would both inform the plot and give the esoteric quality of the film some much-needed gravitas. It’s not difficult to sympathize with a race of people harvested as slaves to computers, but as individuals, the characters in The Matrix do not evoke much empathy. Inception‘s characters, on the other hand, make us feel for them, and in a perhaps unintended twist, in ways that do not always make sense.

In this way, Inception is less like The Matrix, and more like several time travel-oriented science fiction films that double as emotional dramas, for example, Altered States, where virtual realities are enhanced by specialized equipment and pharmaceuticals and blur the line between not only dreams and reality but also existence and non-existence; and La Jetée (and by extension, 12 Monkeys) in which memories and relationships are exploited for somewhat nefarious means.

Inception is also like Somewhere in Time (both the novel and film), another time travel film that utilizes the totem both as a significant plot device and an essential part of the process of travel itself (although in the latter, the totem as an anchor to reality is ultimately a negative one).

Because the dream worlds of Inception are so believable, the characters carry these small totems that only they are allowed to touch. Anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss studied the role of totems in aboriginal people, determining that they ” . . . are chosen arbitrarily for the sole purpose of making the physical world a comprehensive and coherent classificatory system.” In the film, these specific objects keep the main characters from getting confused as to which world is real.

Additionally, both Somewhere in Time and Inception utilize an emotional totem to anchor the films themselves. In Somewhere in Time, it is a portrait of deceased actress Elise McKenna that haunts the protagonist Richard Collier and draws him into her world; in Inception, it is the main character Dom Cobb’s wife, the appropriately named Mal (“bad” or “evil”) who haunts not only Cobb himself, but also the entire film.

Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Robert Fischer (Cillian Murphy)

It is the character of Ariadne, the “dream architect” of Cobb’s team, who serves as a kind of totem for the film. Ariadne is the only female character who does not exist in memories or dreams and the only one who attempts to deal with Cobb’s ongoing emotional problems. Her name indicates her role: in Greek mythology, Ariadne aided Theseus in escaping the Minotaur’s maze. By becoming his anchor into reality, Ariadne becomes Cobb’s totem, and by extension, the team’s totem. (In anthropological terms, a totem is “any supposed entity that watches over or assists a group of people . . . “)

Confusion between the dream world and the real world (and being trapped in one or the other) is a pervasive theme in Inception, and it exposes more of Nolan’s apparent and continuing fascination with Sigmund Freud. Just as the Batman films deal with the Freudian concept of the “unheimlich” (“uncanny”), so does Inception.

“In general we are reminded that the word ‘heimlich’ is not unambiguous, but belongs to two sets of ideas, which, without being contradictory, are yet very different: on the one hand it means what is familiar and agreeable, and on the other, what is concealed and kept out of sight.”

—Sigmund Freud, “The Uncanny,” 1919

In Inception is it not the dual nature of the main character which causes this phenomenon, but what he is actually imprisoning. Not only does Cobb seek to control the dreams of others, he seeks to control his own, which recalls Freud’s theories on the subconscious and dreams, and the dream as wish fulfillment: Cobb is desperately trying to return to his children.

It is not only Freud’s theories which are suggested, but also the dream theories of Freud collaborator and fellow psychoanalyst, Carl Jung: “Freud’s dream approach is retrospective; that is, it refers mainly to past events, placed back in the dreamer’s childhood (psychological trauma, sexual fixations and desires, and so forth). Jung’s dream approach is prospective; it represents a kind of map of dreamer’s future psychological evolution.”

Mapping out a dreamer’s future psychological evolution is an apt description of the process of “inception” as described in the movie: an idea is planted in the dreamer’s subconscious to influence future actions.

In the case of Inception, it is Robert Fischer, the son and heir of a soon-to-be-deceased corporate titan who is the mark, and perhaps the most manipulated of all the characters. When Cobb’s plan comes to fruition, there is a sense of emotional closure on his behalf, not only for his professional successes but also his personal ones. But the fact remains that the true “success” of the plan is the success of those corporate espionage tactics.

Although Fischer himself finds closure through the plan’s success with regards to his relationship with his father, the impetus for this is rendered as ultimately hollow. It is merely accidental, only the byproduct of a more nefarious plot. Furthermore, one cannot even be sure if the reconciliation is “real” as it occurs in a dream world and is informed by Fischer’s own need for wish fulfillment. This poses an irresolvable emotional conflict in the film, one made perhaps more troubling by the sense that Fischer’s reconciliation scene is more honestly achieved and emotionally compelling than Cobb’s.

Inception is a remarkable film: it is well written, well acted, beautifully shot, and a genuine technical achievement. However, all of its charms cannot conceal the callous nature of the central story arc. Personal hurdles are overcome, yes, but at what cost? And to whom? Like Escher’s Ascending and Descending, “both directions, though not without meaning” are perhaps not “equally useless” but instead, sorely lacking in conscience.

8 Responses to “Inception‘s Deception”

July 31st, 2010 at 12:47 am

You’ve done an excellent job of concisely explaining the ideas on which “Inception” is based, Less Lee. I had totally forgotten about the use of a totem in “Somewhere in Time.”

For me, the complex workings of the plot raised too many questions that distracted me from getting involved with the film. I didn’t find the pacing suspenseful, perhaps because I wasn’t emotionally involved. I had no sense of how much Cobb loved his children. I felt something from DeCaprio’s performance when Cobb was explaining to Ariadne about what happened with Mal, but I think I would have liked to have seen the tragic events play out with Mal rather than being told about them.

I realize that Nolan made choices for the kind of film he wanted to make, but for me, they weren’t the choices that appealed to me. From the glowing reviews that I have read, it seems Nolan made the right choices to appeal to the majority of people.

July 31st, 2010 at 10:04 am

Thanks Reed. I’m glad you enjoyed this article.

LLM

July 31st, 2010 at 11:52 am

This is a good review, thank you.

You touched on one thing about this film that, to me, is very interesting; and that’s the way that it has you rooting for the manipulation to work, pulling for our inceptors to not only succeed but survive. Even though Fischer’s reconciliation with his father is fake, you can’t help but think that he’s better off. What’s more, Saito’s motivations for wanting the Fischer empire broken up may not exactly be pure, but it occurs to me that an energy monopoly would be a bad thing for the whole world.

I can’t say that I failed to connect, emotionally, with the characters of the Matrix; but you’re right, all of the characters in Inception are much more relatable. There’s a LOT of “father” stuff going on in the movies this summer, and Cobb provides and interesting counter-point to Fischer senior.

I caught the Ariadne reference too. I kind of love the way that, during her “job interview”, she gives up on trying to draw a square maze and draws a labyrinth instead. It’s not only a reference to the legend, but with the labyrinth being a feminine symbol, it’s her busting up the male paradigm, too.

And you are totally right about the soundtrack. I liked it so well that I bought it.

/geek-out

July 31st, 2010 at 12:47 pm

Thanks for your praise, Lisa! Yeah, I really need that soundtrack. I remember when I first saw Batman Begins I had the same reaction. The soundtrack was so integral to my enjoyment of the movie.

As for “Father Issues,” that’s a good point. Again with the Freudian, Christopher Nolan!

LLM

August 17th, 2010 at 12:05 am

This is a wonderful review and it’s especially lovely that you included the psychological aspects of it. Inception was truly a lovely movie, smarter than the ones we’ve seen lately, which was a much needed change, but something that struck me about it was the callousness of the manipulation. It was brilliantly done, mind you, but any positive feelings Fischer came away with it is ultimately a lie. Of course, Saito is the client and gets what he wants, but I was surprised that nobody really struggled with the moral aspects of effectively tampering with another man’s life. Sure, catharsis is all well and good but going deeply into the subconscious would definitely have unforeseen consequences, not taking into account that if Fischer dissolves his company, he’ll be ruining his own life because there’s no guarantee if he’ll be able to rebuild it – no matter how amazing a business man he is.

I was sorely disappointed by Ariadne, too, because although it was right that she focused on Cobb, I would have thought that acting more or less as the moral compass of the group, she’d have some trouble with it.

Also, I did sympathize with Cobb’s loss of Mal but at times, I felt that his need to return to his children was more out of obligation than love.

It actually takes many reviewing to fully appreciate the movie but in the end, you’ll be left with more questions than answers, which, personally, is what I want in any good story: to let me think about it long after the credits end.

Also, the soundtrack was fantastic!

August 17th, 2010 at 10:39 am

Thanks for commenting, Merry. And thanks for your praise!

LLM

December 24th, 2010 at 11:19 am

Inception was a deception big time. I do not really understand LLM saying the movie was emotionally engage? There was not emotion at all. It was like a long trip going at 40 kph all the way.

Over the top VFX and photosonics doing slow-mo like a shampoo commercial.

The concept of having a dream, within a dream within a dream and the put an idea in somebody’s head to change the future outcome, didn’t excite me at all. Knowing his previous movies, I knew the movie will start at the end and let’s go back to dig. Boring.

Definitely his best movie to date is FOLLOWING.

Lastly, to LLM. If you want to understand what it means an emotionally engage movie where you won’t know until the end what is happening and without Hollywood explosions, watch ABRE LOS OJOS by Alejandro Amenabar.

Since when a British filmmaker has emotions?

December 24th, 2010 at 4:25 pm

Thanks for your instructions on emotionally engaging movies. Also, please see my last paragraph in terms of what I felt about the film overall.

LLM

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.