The Life Of A 21st Century Musician: An Interview With Jim Campilongo (single page)

Published on January 30th, 2010 in: Interviews, Music |Interviewed by J Howell

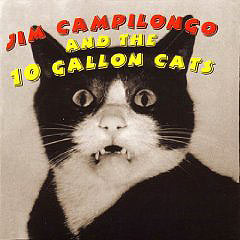

Once, longer ago than I care to admit, I was a kid who’d just picked up his first electric guitar. Around that time, Guitar Player seemed to always have this ad in the back, featuring a hilariously startled-looking cat, for a band called “Jim Campilongo and the Ten Gallon Cats.” That very silly image stuck with me. A few years later, Jim was finally featured in the magazine, and though I still hadn’t heard his music, the descriptions of “ghostly wails emanating from a Vibrolux Reverb” also stuck with me.

Fast forward a few more years and, thanks to the miracle of the Internet, I was finally able to hear Jim, and damned if Heaven Is Creepy wasn’t all I’d hoped it would be and then some. Jim’s newest record, Orange, is out in February on his own Blue Hen Records. Campy just may be the best guitarist working today, and he recently took some time out of his very busy schedule to chat with me.

Popshifter: So you’re at the NAMM (the International Music Products Association) show right now, is that right?

Jim Campilongo: That’s correct, yeah.

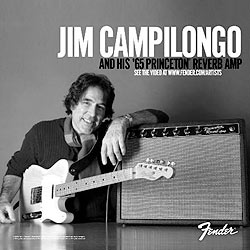

Popshifter: And they’re debuting the Fender Jim Campilongo Signature Telecaster at the show, right?

Jim Campilongo: Yeah, that’s right.

Popshifter: So you must feel like you’ve “arrived” to have a Signature model Telecaster?

Jim Campilongo: Well, you know, in some ways, yes. . . I don’t know if it’s the equivalent of winning an Academy Award, but it certainly is nice acknowledgment and I really, really feel lucky and excited about what Fender’s doing for me.

Popshifter: Right. . . I’m sure it can’t feel bad. . .

Jim Campilongo: No, it doesn’t. . . it certainly doesn’t, you know. It’s like a lot of things: it goes in increments. And sometimes those increments are so small that it’s hard to see when a rose opens, or the sun rises, and certainly, there have been many increments that have occurred to get this guitar to today.

We’re still fine-tuning it to some degree, but I’m definitely really excited about it and I think the guys at Fender are. . . their hearts are in the right place and in my mind and in theirs, we want to make a great guitar and we’re hoping that some people buy it and make some great music on it and cherish it. I’m also hoping that some people will go out and listen to my music, who haven’t heard it before, and I think Fender is aware of that as well. I find that exciting, too.

Popshifter: Speaking of your music, you have a new record, Orange, that comes out February 16—

Jim Campilongo: That’s right.

Popshifter: —with Anton Fier as producer, who was the original drummer in the Lounge Lizards, played in Golden Palominos. . . I noticed listening to this record, compared with Heaven Is Creepy, it’s difficult to quantify in a way, but I guess to me it’s more of a “New York”-sounding record.

Jim Campilongo: Yeah. I mean, I’ll take that. It definitely was a conscious thing, to have an “All New York” cast and crew, on my part. I’m not taking all the credit for the difference between the records; Anton’s contribution was great, but in the past, I’ve at least had my big toe in San Francisco, whether it be engineering it there, mastering it in SF, or something like that, and I didn’t do that. This record is all New York. The furthest we got was Brooklyn. I think Anton’s influence, some of his goals and my goals. . . yeah, I think that’s great. I love New York and its history, and I hope that I can contribute something to the city with my residency [at the Living Room, every Monday night] or my presence, being there, because I know it gives a lot to me. I guess it does sound “New York,” but there are so many versions of “New York.” If you’d said “What’s the most New York thing you can think of?” I’d probably have said On The Corner, Miles Davis, or Charlie Parker or something like that.

Popshifter: Or you know, someone else might say the Velvet Underground. . . there are any number of things that are “New York”

Jim Campilongo: That’s totally valid. The Velvet Underground. So how is my record New York? I don’t wanna put you on the spot, but I’m curious. . . (laughs)

Popshifter: There’s something about it. . . I mean, it’s not like there wasn’t “fire” in your playing before, but it seems. . . and granted, not every song on the record is like this—”Awful Pretty, Pretty Awful” is about as far away from this as it could possibly be—but some of the songs, I’m thinking “Backburner” or “I’m Hellen Keller, You’re a Waffle Iron”. . .

Jim Campilongo: Yeah. That’s pretty New York. That outro, the way there’s a long feedback. . . You’re right. I never really thought of it that way. I appreciate it. And “Awful Pretty, Pretty Awfu,l”, you know, I didn’t want that on the record, or didn’t consider it. I had written it after seeing a country swing band. I went home and I wrote that, and I sent it to a musician in this country swing band—the guitarist—and said, “Hey, I wrote this song for you. I was inspired by seeing you guys and I wrote this song.” Between me, you and the walls, he never responded! (laughs)

I thought it was kind of cool, and then I forgot about the tune. I was practicing it one day and I was going through some MP3 files of tunes I’d written, and I’d been relearning it and Anton came over. I’d been playing it with a Boomerang looper as a rhthym—just me and me, basically—and Anton said “Hey that’s really good! You ought to put that on your record” and I said, “Yeah, but this is a Ten Gallon Cats kind of thing” and he says, “No. That’s your thing. We gotta have your thing on the record. . . ” And I said “OK.”

And I’m really glad it’s on there, but I was concerned, thinking, well, I’ve got this acoustic song called “Orange”, it’s really pretty, now we have “Awful Pretty, Pretty Awful”, now we have “Backburner”. . . and I was really worried about how the record would fit together. Anton really assured me—promised actually—that the record would have continuity. And I think it does. You know, I don’t think it has the continuity of Miles Davis’s Kind Of Blue, but you know . . . I don’t get sick of myself [on it], and I do sometimes. I mean, how much can a guy do for 40 minutes, instrumental, with a Telecaster? After 40 minutes, I’m done.

I think what’s successful with this record is that it’s like a real good Jim Campilongo iPod shuffle. If I get tired from, say “Chelsea Bridge,” something that’s intense or kind of draining, there seems to be another flavor, other flavors that kind of energize the experience. I have to say, I’m happy with that.

Popshifter: I’m really glad that you ended up choosing to put that song on the record. It’s a great song, and it’s nice in that, as much of a kind of “New York” record as it is, it has these moments of not being jarring in the sense that it’s completely different from one song to the next, but it keeps it—

Jim Campilongo: Well, it’s almost jarring. If memory serves me correctly—and I should know this—”Orange”, the acoustic duet, happens after “Helen Keller,” and it does take a couple of seconds to get used to that. There’s this dinosaur-scream feedback, and then it goes into this thing that, in my wildest dreams would sound like Chopin meets Santo & Johnny. . . (laughs)

Popshifter: Right.

Jim Campilongo: It kind of is successful at that. It works, you know. I think it’s ’cause, for fear of sounding full of myself, they’re both good, and you know, like Duke Ellington said, there’s only two kinds of music, good and bad. And it isn’t like a “business card” record. “Now Jim Plays Chet Atkins style! Now Jim Plays Velvet Underground. . . ” It’s kind of like, well, this is all me. But I’d say that’s the most “jarring” part of the record. But hey, you know. . . good!

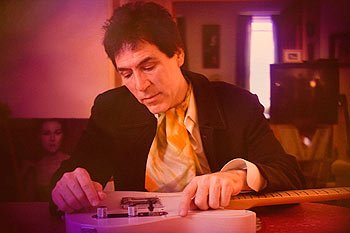

Photo © Todd Chalfant

Popshifter: I think the thing that’s great, if you look at the track listing, there’s “Backburner,” which is really energetic, then there’s “Awful Pretty,” then “Blues For Roy” followed by “No Expectations.” Granted, I’m a guitar player, too, so sometimes it’s hard to put myself out of that frame of mind, but I know at least playing this record for friends that aren’t musicians, that helps it come across not so much as a “guitar guy” kind of record.

Jim Campilongo: I’m so happy to hear you say that! It seems so hard to break out of this “gunslinger” thing, and I still feel that I’m not that. I could see why people would call me that, but it’s really limiting, and it’s not the purpose I want my music to fill. I want “No Expectations” to just be a really good, heartfelt reading of that song. I want “Backburner” to be, I dunno, something three-dimensional and psychedelic. I really don’t want to just make records for “guitar player guys.”

Even somebody like Chet Atkins, he was coming from a place of artistry and great craftsmanship. And that’s why I still like those records; it’s why they make me feel good. When I hear descriptions of my music that are like, “If you like (insert flashy guitar guy name here), you’ll like Jim Campilongo,” I always think, “I don’t know what they’re listening to.”

Popshifter: That always confounds me a little bit, too, with a lot of those “guitar-y” things. Not to knock any of those styles of music necessarily, but a lot of time it seems to be that way. With instrumentalists, it seems sometimes that they forget that music is about some kind of connection and expressing yourself, but also connecting with the listener or audience, and sometimes they lose sight of that, getting caught up in the technicality of it. And I know that’s kind of an old complaint, but it’s really true, you know?

Jim Campilongo: Yeah, except that. . . I have to take some responsibility, too. I mean, I don’t think Bill Frissell is going to get accused of being a gunslinger, or be described as being a gunslinger, because he just doesn’t play that way.

Popshifter: Good point, but then, Frizz is. . . well, Frizz.

Jim Campilongo: Yeah. But you know, I do have this laser-beam, take-no-prisoners sound sometimes, and it can be very monolithic. I’m not saying you’re wrong, or changing sides. I agree; that’s why I’m so pleased to hear you say that. And yet, sometimes I feel a little misunderstood, especially when there’s songs like “Orange.” I have 95 songs on iTunes, and I think a lot of those songs are worthy, credible compositions and I kinda don’t hear that that much.

I hear things like, “Wow, great tone, dude!” (laughs) and I think, not to say nothing is ever enough, I think Paul McCartney’s bummed that John Lennon gets some credit for “Yesterday” that he doesn’t deserve, you know (laughs). Hasn’t Paul McCartney gotten enough credit? You know, Jesus!

So I think there’s a natural inclination towards “nothing is ever enough,” and I hope I’m not guilty of that, but I wish people’d , instead of hearing, “Good tone, dude!” somebody would say something like, “Wow, the fourth song was really pretty.”

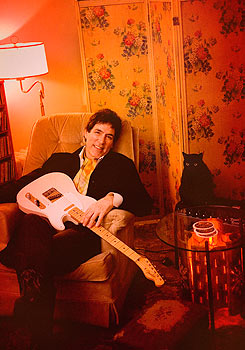

Photo © Arthi Krishnaswami

Popshifter: I think that’s what separates you from a lot of those other [guitar-intensive] things, Obviously you’re a very talented guitarist, but even listening to you play instrumental songs, it’s not like that’s what it’s about. It’s being very technically able, but using that to serve the composition, the piece of music. It’s not wall-to-wall, how-many-notes-can-I-play stuff, and I think it makes a difference. It seems to make a difference to people who aren’t guitar players, especially.

Jim Campilongo: I played a GIT [Guitar Institute of Technology] gig/seminar on Thursday, (yesterday), and I had an L.A. rhythm section: the bass player was David Piltch, a really great bass player—he’s played with Ribot, he toured with kd lang for years—but he did the gig, and at the end of the gig he goes, “You know, I figured it out. I figured out how to play this gig.” and I said, “Well, what do you mean?” and he said, “I just figured out, I should play like you are the singer.”

Popshifter: Exactly.

Jim Campilongo: Yep. That’s it, exactly.

Popshifter: Back in the late ’50s, early ’60s, you’d have guys like Chet or Les Paul who would be doing basically “guitar” records, and it was still “pop music,” and it was approachable in that sense. There was a strong sense of melody, there would be things that were pretty, it wasn’t just wall-to-wall guitar. It’s refreshing to hear things that aren’t necessarily exactly that kind of thing, but that approach the songs almost the way a singer would, as opposed to, “Watch me wail for forty minutes!” That’s kind of hard to sit through!

Jim Campilongo: You know, I don’t think it’s natural. I don’t think it’s natural to hear a soloist that doesn’t pause for breath sometimes, whether it be on piano, guitar, or any instrument that doesn’t require breath. At least in my mind, even Allen Holdsworth has pauses that would seem natural, where one would physically take a breath. Obviously someone can’t sing what Holdsworth is playing, or it would sound really crazy, but when he plays, it’s almost like he creates. . . pixels, like if you got really close to a television you’d see millions of dots, but if you back away from it. There’s an image.

And I think that’s what he does, at least for me; I think he’s an outstanding artist. Well, a lot of it, or some of it may get a little tedious, but he has all these pixels that create one image that make all his notes really beautiful and have a sense of validity, and he stops for breath. It’s interesting; everybody has a different approach. That’s another side, another thought on it. It’s interesting to talk about.

Popshifter: I saw a Fender YouTube clip featuring you when the new Fender Princeton reverb reissue came out. I think you called it a “personal, lyrical” kind of approach. How much of that comes from working with singers, like playing with Norah Jones in the Little Willies or with Martha Wainwright? Or did you always approach it that way?

Jim Campilongo: Well, I always approached it that way. Not to say that they haven’t influenced me, they have. But always, in playing an instrumental. . . maybe I learned it from Roy Buchanan or the people that I listened to, like his reading of “Sweet Dreams.” I knew that song was about heartache, some kind of yearning, just by the way he played it. But I always will try to express what the song is trying to say originally.

A song like “Stardust,” or something like that, I’d really think about the lyrics, and that’s a sad song. It’s about someone who is at the end of their life I guess, looking back at a time when their heart was filled with love and hope, and now maybe they experience those feelings by retrospection. I would think about that like an actor approaching a role. What do they call that? “What’s my motivation?” or something like that.

Popshifter: Right, and then you have to go into that with it in mind that no one is going to be singing; you have to get that across with your instrument.

Jim with Norah Jones

Photo © Jim Campilongo

Jim Campilongo: Which to me, I prefer. To me, it’s like I could maybe say more because of that. On Orange, there’s “When You Wish Upon A Star,” and I felt like on that tune, I wanted to play it like the guy didn’t get his wish, to be honest.

I remember hearing it when I was a kid, they used to play it at the beginning of the Disney show that was on Sunday nights or something, and we’d never watch it. I think my parents would watch something else, but now and then I’d hear that song and see Disneyland with the fireworks going off. . . I dunno, this might be before your time. Anyway, I used to hear that song and I remember being really moved by it. It wasn’t like, “All my wishes are gonna come true!” I never really felt that way about that song. I always felt it was just about hope, maybe a hope that might get fulfilled or not. So I played that tune like someone wishing for something, but they’re not gonna get it.

Popshifter: It’s definitely not a rote reading of the melody.

Jim Campilongo: (laughs) Exactly, yeah. . . I’m rarely on autopilot, and I shouldn’t be.

Popshifter: Going back a step, as I said earlier you play with Norah Jones in The Little Willies and also with Martha Wainwright. Do you prefer playing as an instrumentalist and bandleader or as a sideman?

Jim Campilongo: Well, I guess I would prefer being a bandleader or playing my own music but, it’s much easier being a supporting member. It’s really hard to play the head, or play the tune and then you’re supposed to solo. Sometimes I think, do I really wanna hear a solo? I just played for a minute and 20 seconds and how am I gonna make this solo? Do I wanna hear anything? And I’ve learned how to do that playing in different registers of the guitar.

On “The Prettiest Girl in New York” off Heaven Is Creepy, I play a solo in the upper register, and I never really did that until I started doing my own thing. It’s a lot different than playing a song. It’s going along, and you think, “Geez, in about ten seconds I’m gonna play, I’m gonna turn up to ten and I’m gonna play a solo. . . 10-9-8-7-6. . . “(laughs) Okay!

You know, to me it seems a lot easier, and it’s easier in that one could just complement the main player, and it’s also easier in that when the gig’s over, you just get out. Everybody wants to talk to Norah, or everybody wants to talk to Martha.

I’m not trying to sound like I hate talking to people because I don’t, but it’s much easier. All that said, and never taking the easy path, I would prefer playing my own music, having the satisfaction of composing something and hearing it. But I really do like both, I wish I would get even more sideman calls than I do. I know I have a strong voice, sometimes people might think it might be a bit much. They don’t want Rod Steiger or Keanu Reeves or whoever, they want someone who’s maybe a little less attention-grabbing. Me, I’m not trying to beat my chest or sound bitter, because I’m not, but I miss that sometimes, where if someone had a unique voice as a soloist, that used to be an asset. To some degree, that’s not as important anymore. A lot of the music I hear, it doesn’t make many waves.

Popshifter: I would agree, definitely in the realm of “popular” music.I think there are still things, but maybe you have to dig a little deeper to find them. This brings me to something else I wanted to talk with you about: the difference between being a musician in San Francisco and New York, since you’ve been there seven or eight years now. And also more generally: what is it like making a living as a musician in the 21st Century as opposed to the way things used to be in the music industry even 15 or 20 years ago because so much has changed?

Jim Campilongo: Musicians have to work so hard now. Musicians have to work at promoting themselves, whether it be on Facebook or MySpace, or through self-arranged or partially self-arranged interviews, etc. You have to manage your website, you have to get your photos up, and with all that there’s follow-through, let’s credit the photographers. . .

[Suddenly, our connection is lost, so I call Jim back.]

Jim Campilongo: Hey! Where were we?

Popshifter: We were talking about crediting photographers and there you go, the life of a 21st Century musician: calls get dropped in the middle of an interview. . .

Jim Campilongo: (laughs) I’m surprised that’s only happened once so far! So yeah, I have to make sure I credit the photographers.

If I cover “No Expectations,” I’ve gotta make sure I have the right publishing notes on the CD; I’ve got to go to the Harry Fox website and put in the proper UPC number that I’ve purchased separately into their database for the amount of CDs that I’m going to print; and pay those costs up front, before making an invoice to my distributor; before making 1099s for the musicians whom I’ve paid; before making sure that the contract I have with Fender in regards to the Custom Shop guitar is good; arranging a time with my lawyer; printing out that contract. . . and realizing that my printer is out of ink and I have to run to Staples; but before that I have to go to the post office to send an international package that I know is under four pounds, so I use the green customs form instead of the white one. . .

I could keep going on and on and it might get tedious, and I might even seem whiny, but I want to make a point, because I occasionally hear how fortunate I am to live in a time where I can manage my own career.

Sometimes I have mixed feelings about that, and there’s no way of knowing if I would’ve existed in 1972 when musicians basically just played, or even 1962. But I can pretty much guarantee you, I doubt if Thelonious Monk would be able to survive in the year 2009 as a musician. I mean, even though he’s a genius, I don’t think he had the skill set that would allow him to book gigs and do the things that a musician nowadays does, unless he got a booking agent and a manager and a label who did all that for him.

Popshifter: It’s definitely a lot more than plugging a Tele into a Princeton and that being that.

Jim Campilongo: Yes, and you know, that really bothers me, because a lot of days, I have a lot of trouble making my way to my guitar. That’s really what I want to do: I want to grow as a musician, I wanna learn tunes, I wanna develop, I wanna go through the George Van Eps guitar book and learn some inversions in keys that I’m not completely comfortable with, get more of a 20/20 insight into my instrument.

And a lot of my days, ALL my days, are spent doing exactly what I just described. The fact is, because I’m here in L.A., kinda working my butt off, and not at the office in New York, means that it’s gonna be triple duty when I get back. Stuff is mounting that I just cannot do here. That seems to be the story of my life, especially since I moved to New York.

Like I said, I don’t know if I would’ve survived in the ’80s, or if a major label would’ve allowed my music to surface, or if they would’ve invested in it, so maybe I should just feel fortunate. But sometimes, I worry that artists can’t be as good as they could potentially be because they’re doing so much clerical work. I think I answered your question, I’m not sure, you asked about being in New York and I started going on a rant. . . (laughs)

I would say that all of what I just talked about is accelerated as a result of living in New York. It’s more competitive: the time zone’s different so you still get up early, but you’re still getting east coast calls at 7 p.m., 8 p.m., and then it’s time, if you’re lucky, to go to a gig. . .

Popshifter: Right, exactly, at the end of the day, you still have to have the wherewithal to, you know, play, and have the energy to make it worthwhile.

Jim Campilongo: It is a dilemma. I feel that I haven’t reached my potential as a musician yet. And that’s one of my great ambitions and desires and goals. Now and then, when I can fit in a couple hours, three hours, maybe four in a day, when I’m not completely distracted and exhausted, you know I really start playing well, in a way where I’m hitting a plateau here that I’ve never seen, and that’s really what I want.

It’s definitely more intense in New York, but you know it’s great; everyone else there is doing it, too. When you get together, nobody complains, everybody’s serious about the music, and nobody takes it for granted. It’s an intense place.

Popshifter: New York has a reputation for being an intense place going back to, well, forever, and then on top of all that, you’re still doing lessons, right?

Jim Campilongo: I give lessons, but not that many. I was giving maybe 30 lessons a week living in the Bay Area; in New York I give about five a week. Generally, New Yorkers don’t want to take weekly lessons. They’re too busy. Everybody teaches, so you can get a lesson with Mike Stern, Howard Alden, or Bucky Pizzarelli, people teach who you’d think wouldn’t.

I love that about New York, and the good thing is there are a number of ways to make some money; you just don’t have to give 30 lessons a week. Hopefully, you’re getting a call for a commercial, something. And I do the lessons by mail, too.

Photo © Todd Chalfant

Popshifter: Which seems like a great idea. Prior to this interview, I went through and played the samples on your website and they were great.

Jim Campilongo: Thanks!

Popshifter: Everybody learns differently. I think I maybe would do better in person, but it’s great to get sort of pointed in the right direction.

Jim Campilongo: Eventually, I think I’m gonna do some kind of instructional DVD. Who knows, it might be 3D by the time I do it! (laughs)

Popshifter: That’d be great, actually.

Jim Campilongo: (laughs) That’s next, I guess! I’ll be reading about 3D technology instead of practicing “Stella By Starlight.” (laughs) But yeah, I think the lessons are pretty good; I’m proud of ’em.

Popshifter: Looking through the list on your site, the only thing I thought was lacking was that I saw you had lessons for several of your own songs, but “Pepper” wasn’t one of them. .

Jim Campilongo: Aww, thanks. (laughs)

Popshifter: I’ve been trying to sort of pick my way through it, you know. I’ve got the melody as single notes pretty well down, but the harmony. . . (laughs) You should do a Lesson By Mail of “Pepper.” That’s my advice. (laughs)

Jim Campilongo: (laughs) Thanks! Maybe I will. I’ll let you know when I do. (laughs)

Many thanks to Jim for taking time out of his busy schedule to talk with me!

Orange will be released on February 16. Jim will be playing five dates in New York City in February; the CD release party will be at The Living Room on February 15. Check out Jim’s Official Site or MySpace page for more details.

2 Responses to “The Life Of A 21st Century Musician: An Interview With Jim Campilongo (single page)”

January 31st, 2010 at 4:03 pm

[…] To read this article as a single page, please click this link. […]

December 5th, 2011 at 10:43 pm

[…] to argue that smaller ’70s Fender amps somehow just don’t sound as good, consider this: Jim Campilongo owns and uses three ’70s Princeton Reverbs, two ’70s Vibroluxes (including one with a […]

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.