Cosgrove Hall Animation: Danger Mouse And Count Duckula

Published on November 29th, 2009 in: Cartoons, Culture Shock, Issues, OMG British R Coming, TV |By Lisa Anderson

My love for things British goes way back. Like many people my age, I grew up with Nickelodeon, the cable children’s programming network. One of my favorite shows was Danger Mouse, the first British cartoon to break into the American market, and its later spin-off, Count Duckula. Both were from the animation studio Cosgrove Hall.

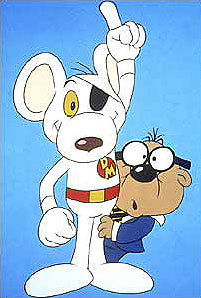

The title character of Danger Mouse is a secret agent, a white mouse with an eye patch who lives in a pillar box (mailbox) on Baker Street in London. His hapless but earnest sidekick, a hamster named Penfold, helps D.M. (as he is nicknamed) defend crown and country. Their principal nemesis is Baron Silas Greenback, a gravelly-voiced toad in the mold of a Bond villain, with crow for a henchmen and a white caterpillar (what else?) for a pet. Colonel Kay, D.M. and Penfold’s boss, looks like he might be human, but is alternately suspected by fans of being a walrus or a chinchilla. Since the main characters are all small animals, any action in the human world takes place, for the most part, to scale. As with all the best kid’s shows, there are sly jokes for the benefit of adults, too.

Count Duckula started out as a villain on Danger Mouse, an actual vampire with a Disney-duck lisp. When he got his own show, he also acquired two loyal retainers: Nanny, a large hen, and Igor, a vulture. We learn that Duckula has been staked and resurrected throughout history. “This latest reincarnation,” the intro explains, “did not run according to plan.” Nanny uses ketchup instead of blood in the resurrection ritual, and to Igor’s horror, his dark master comes back as a vegetarian. The central tension of the show is Duckula trying to break into show business, while Igor tries to lure him back to his evil ways. In the midst of all this, our heroes also have to elude Dr. Von Goosewing, a crackpot vampire-hunter who can’t comprehend that Duckula now means no harm.

In researching those programs, I was actually surprised to learn that there were 161 episodes of Danger Mouse and only 65 of Duckula. I feel, correctly or not, that I have seen many more episodes of Duckula. I can remember being overjoyed when I saw the Thames Television logo pop up before an episode of Danger Mouse, with its signature trumpet tones, because that meant an episode that I hadn’t seen, or hadn’t seen as many times. In some ways I like Duckula better, although both programs were formative for me in their own way.

For you see, because of these shows, I cut my teeth on British humor. I didn’t join the Flying Circus, so to speak, for another few years, but Danger Mouse and Duckula prepared me for a range of other British works, including Monty Python movies, Doctor Who, Absolutely Fabulous, Red Dwarf, and Are you Being Served? More than that, it conditioned me to appreciate that type of humor regardless of where it came from: dry and subtle, with turns to the sarcastic, corny, or absurd. When I was little, I thought for a while that Robin Williams was British—because all of the funniest people were British, after all. I don’t consider “getting” British humor to be a matter of intelligence, but it does seem to be something that you either connect to or you don’t. And I do.

Throughout the years it’s been a touchstone of sorts to connect with people in my age range, too. One time my sister, who is nine years older than me, brought home a college boyfriend. On a whim, we showed him episodes of Danger Mouse, because he had never seen it before. He was nonplussed. When her next boyfriend was familiar with Danger Mouse from childhood and liked it, I told him how much cooler he was than his predecessor, which pleased him immensely. She married that one—not for his taste in cartoons, obviously, but that was one clue to a compatible personality.

My parents remember the musical British Invasion. My father once told me that it was a somewhat humbling experience for Americas. After victory in the Korean War and a successive economic boom, the United States needed the reminder that people from elsewhere could do things well. My parents would have raised me with that knowledge anyway, and as it was, I grew up in a much smaller world. The cartoons of Cosgrove Hall not only gave me hours of joy, but insight into the spirit of a nation so closely connected to my own. For all of these reasons, they are some of the British things I love.

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.