Look Who’s Growling, Too: Our Deep, Abiding Love of Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby

Published on September 29th, 2008 in: Halloween, Horror, Issues, Movie Reviews, Movies, Retrovirus |By John Lane and Less Lee Moore

Hands-down, Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby is one of our favorite horror movies of all time. We love it as much for what it doesn’t do as for what it does do. It seems that there’s a storm cloud of creepiness that settled upon this movie before, during, and after which makes it all the more fascinating. Like a lot of other things from the late sixties, it is a sinister relic from a haunted time. So here are our reasons why Rosemary’s Baby—behind and in front of the camera—is one of the most enduring, complex horror films ever committed to celluloid.

Screencap from dj_capslock

The apartment building where most of the action takes place is The Dakota, the infamous and imposing building in NYC where John Lennon was assassinated. Rumor has it that the ghosts of Lennon, Boris Karloff (most famous for playing the Frankenstein monster), and turn-of-the-century (the other one) children roam the premises. In Ira Levin’s original 1967 novel, the building is referred to as The Bramford, but interestingly, The Dakota is mentioned as a place Guy and Rosemary Woodhouse also considered when they were looking for apartments. They are warned by a friend of Rosemary’s against renting at The Bramford because it was the site of satantic worship and child murders years before.

Mia Farrow (Rosemary Woodhouse) was served with divorce papers by hubby Frank Sinatra’s legal representation on the set of the film. Once you’re done chewing on the fact that Mia Farrow was 21 when she married a 50 year-old Sinatra in ’66, then ponder just what it takes to be given the heave-ho by Sinatra in the first place. The year of the release of Rosemary’s Baby found young Mia chilling out with The Beatles, Mike Love, and the Maharashi in the Himalayas, if that gives you any idea of where her head was.

According to Wikipedia, Farrow’s acceptance of the role of Rosemary “incensed Sinatra, who had demanded she forgo her career when they wed, and he served her divorce papers via a corporate lawyer, in front of the cast and crew midway through filming.”

In addition, the papers were served during the filming of a scene in which a stressed-out, pregnant Rosemary is crying in her kitchen and being consoled by friends (who are also keeping husband Guy out of the kitchen). Polanski wanted to stop filming but Farrow refused. The juxtaposition of a controlling real-life husband/actor (Sinatra) with that of a controlling fictional husband/actor (the character of Guy is also an actor) is intriguing, to say the least.

Screencap from dj_capslock

John Cassavetes (Guy Woodhouse) clashed frequently with director Roman Polanski, which perhaps added an additional layer of tension to the proceedings. While Cassavetes took on Hollywood star roles to make money for his own artistic film endeavors on the side, he looked down upon the very star system that put bread and butter on his table. He complained frequently of the over-the-top things that Polanski ordered him to do, thinking them too obvious and at times, too demeaning.

One senses the “Let’s make love” scene, where Guy and Rosemary have just moved into their new apartment unit, is a scene that Cassavetes didn’t particularly like doing. And let’s face it, while Rosemary strikes me as particularly hot, there’s something off-putting about Cassavetes appearing to sigh reluctantly and yank the lamp-cord out of the wall as if to say, “OK, let’s get this over with.” The movie is replete with scenes like this where one gets the feeling it’s the umpteenth take.

This all results in a particularly striking case of life imitating art (or vice versa) as Cassavetes portrays Guy with a supercilious self-centeredness that makes one’s skin crawl. One feels an immense sympathy for poor, naïve Rosemary the ex-Catholic; Rosemary who just wants to have a baby and spend time with her young friends; Rosemary who we sense was a pawn in Guy’s world long before his pact with Old Scratch’s septuagenarian buddies. Rosemary is being smothered by the patriarchal world that would lead to the explosion of the feminist movement just a few years later. It is this manipulative, claustrophobic world that seems a larger threat than any Satanic spawn could ever be, and perhaps this strange, dark air is the true evil of the film.

A strange, dark air seems to surround the director Roman Polanski as well. The year after Rosemary’s Baby was released, his pregnant wife Sharon Tate (along with a host of others) were slaughtered by Charles Manson’s minions in their California home. Polanski was out of the state working on another film, and thus was spared direct involvement in that nightmarish evening.

Apparently the dark air didn’t really touch Ruth Gordon (Minnie Castevet) as she won an Oscar for Best Actress in a Supporting Role in ’69 for her role. And then later went on to play perhaps her best role ever as Maude in Harold and Maude. Maybe that was a perk for representin’ one of Satan’s minions? Who knows!

Screencap from dj_capslock

Now let’s get to the heart of some of the things that make this film tick as a nonpareil horror movie, without giving the whole show away:

That opening scene with the credits is one of the most eerie and subtle openings ever, as the camera pans down to the Dakota and there’s that uncanny, wistful “la la la” singing (and it is actually Mia Farrow herself contributing those vocals). It’s a sunny day over the dark and gloomy building; nothing bad has happened yet, but you already feel the impending sense of doom squeezing your heart.

Screencap from dj_capslock

There’s a classic Good-versus-Evil/God-versus-Devil paradigm that runs through this movie on various levels. One of those levels has to do with the two doctors that Rosemary consults. Dr. CC. Hill, as played by Charles Grodin, is the very picture of understanding and calm, and he’s Rosemary’s first obstetrician. During the course of things, under heavy persuasion from “all of them witches,” she switches doctors and seeks advisement from Dr. Sapirstein, a paternal, Santa-Claus-like figure on the surface. Under his care, she chops her hair off and becomes increasingly anorexic-looking. But the creepiness doesn’t stop there. I won’t blow the twist, but suffice to say, the trademark smarmy/oily Grodin character acting seeps forth at the end in a scene that will put your stomach in knots.

Persistent neighbor Minnie Castevet keeps bringing over “vitamin drinks” for Rosemary during her pregnancy. The droning insistence—from the neighbors to her own husband—that Rosemary eat every bite is downright creepy. What’s even creepier is the drugged dessert that Minnie sends over with Guy specifically for Rosemary to eat on the night the baby is conceived. Farrow delivers one of the most chilling, subtle observations after downing her first dose of the anti-Cosby/Jello-Pudding, along the lines of “It has a chalky sort of undertaste.”

Again, without giving it away, when Rosemary dreams, the viewer feels like they’re dreaming, too. Polanski had a remarkable gift for committing that weird feeling of half-asleep/half-dream state to film (for example, 1965’s Repulsion with Catherine Deneuve). Something terrible is indeed happening but we wonder if most of the dread is in our minds (or Rosemary’s). Ironically, the thing that Rosemary doesn’t catch onto until the very end is the one thing which she actually saw, albeit while dreaming.

Screencap from dj_capslock

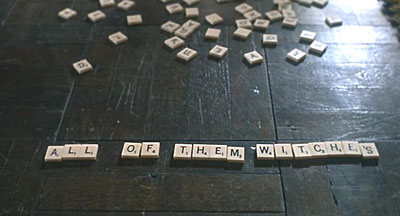

The most remarkable chain of events in the film occurs when our heroine starts making connections rather quickly, all with the use of some Scrabble tiles and some further research based on her hunches. In clumsy hands, this would look like a ragged episode of Scooby-Doo, but here, we’re able to buy into this nightmarish world. It helps too that Rosemary, while sitting in the doctor’s waiting room, actually picks up a copy of Time magazine that trumpets the headline, “Is God Dead?” One should note this was a real cover story issued in April 8, 1966, in blood red lettering against an all-black background, groundbreaking for Time magazine in the mid-sixties.

And now for some odd coincidences regarding Rosemary’s Baby. . .

Remember, that Time article came out April 8, which is also the birthday of Julian Lennon, son of John who was slain outside The Dakota, which brings us back to the movie location.

Speaking of John Lennon, in the movie Yellow Submarine, a Frankenstein monster drinks a potion (no word on whether or not it had a chalky undertaste) and turns into John Lennon! Yellow Submarine came out in 1968, same year as Rosemary’s Baby.

Charles Manson claimed that the Beatles were speaking to him via the White Album, which was released in 1968. So let’s tie this all together, in a loose conspiratorial way. It was said that Charles Manson’s real target was none other than record-producer Terry Melcher who had dwelled at Roman Polanski’s home before selling it to Polanski and Tate. Why Melcher? Because Melcher worked with The Beach Boys, and Melcher had dismissed the songwriting “talents” of Manson, even though Dennis and Brian Wilson had indulged Manson a bit more in the studio. Going full circle, connect the loopy dots: you’ve got Polanski to Melcher to Manson to Beach Boys to Mike Love (Beach Boy) to Mia Farrow to The Beatles. . . and back again.

With all this in mind, one recoils from the recent news that Michael Bay is producing a remake of Rosemary’s Baby. Not all horror remakes are bad (David Cronenberg’s The Fly and John Carpenter’s The Thing come to mind as exceptional re-imaginings of classic originals), but one suspects that Bay’s previous involvement with remakes has been less about a genuine admiration for the source material and more about the “almighty” dollar. At least Cronenberg and Carpenter had experience with horror films.

Screencap from dj_capslock

The other troubling aspect is of course the question of, “Why?” or perhaps more specifically, what can be added to Rosemary’s Baby to make it more relevant than it already is? Young women who have grown up with post-third-wave-feminism freedoms might not have the pop-cultural background to grasp the significance of a time when a Catholic marrying a Protestant was grounds for dismissal from one’s family. Translating the plot into a modern setting would have to be done with a restrained and skillful hand, not special effects and explosions.

All movies (books, films, television) are a product of their time, but when times have changed so drastically—particularly the landscape of horror films—it seems certain that a few million dollars and a couple of trendy, twentysomething actors won’t be able to add anything more to Rosemary’s Baby‘s still-potent brew.

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.