Don’t Hate the Cannibal, Hate the Game: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre

Published on September 29th, 2008 in: Halloween, Horror, Issues, Movie Reviews, Movies, Retrovirus |

Screencap from mertonfanatic

What you are about to see is a snuff film.

John Larroquette’s ominous, baritone voice-over invites you to be a voyeur to “one of the most bizarre crimes in the annals of American history.” Though clearly a work of fiction, his tone, and the following sequence of gruesome crime scene snapshots (set to a rather creepy, high-pitched “whiny noise”), start to plant the seeds of unsettlement, or at least the feeling that you are bearing witness to something all too real. Remembering back to that particular viewing last October, the theatre had received a reel of the film that was of rather poor quality. As a result, the images I saw were grainy, adding further to the developing idea in my head that this could have been an actual snuff film.

Childhood fears of backwoods rednecks.

Growing up in the southern United States, I have occasionally encountered people and places that immediately sent shivers up my young spine. My bus might pass an abandoned-looking (but still obviously lived-in) trailer park or forgotten older house, and my mind would race with ideas as to what sorts of macabre happenings took place behind their doors. In my day-to-day adventures, I began to realize that I never felt totally comfortable in the homes of my more redneck-y friends. I always got a sense of unease amongst the hunting enthusiasts, uneducated (and somewhat illiterate) Confederate flag-wavers, and those who proudly embraced greasy, long hair and cutoffs unironically.

Screencap from mertonfanatic

The truth is, I rarely had a bad encounter with any of these people, but yet, I was never comfortable. I always wondered when the other shoe would drop and I would see why I should have just trusted my initial instincts to stay very far away. The grandfather’s house in Massacre reminded me of once-beautiful-now-abandoned early 20th century homes I had seen in the more rural areas where I grew up, while Leatherface and his demented family represented that unspeakable, unexplainable fate that certainly waited somewhere beyond the tall blades of grass of those neglected backwoods yards.

Unusual atmosphere.

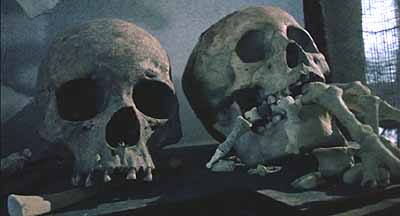

Littered with chicken (and human) bones and adorned with skins, blood, and meat hooks, Leatherface’s house is seemingly decorated to resemble a slaughterhouse retrofitted to a quaint cottage. This juxtaposition of a normally calm, pleasing exterior with the visual and auditory horrors immediately apparent upon crossing the threshold, while typical for a horror movie, were even more obvious in Massacre.

Screencap from mertonfanatic

The soundtrack.

I have alluded to how much simple sounds got to me in the opening sequence. Nothing creeps me out more than the unknown and in many cases, I was unable to trace the source of sounds in scenes. Was that a bird, or a scream? What instruments are creating these haunting noises? Why can’t I place it? Or am I just hearing things? Noises built on top of other noises and after a while, I gave up trying to tell myself that I could rationalize what I was sensing. And through the confusion, my fear became heightened. I can’t trust my senses, so what can I count on?

Screencap from mertonfanatic

There is no escape, there is no resolution.

From the creepy gas station attendant to the eccentric, mentally disturbed, and physically revolting presentation of the entire Leatherface clan towards the end of the film, the cruelty and violence enacted on the victims in the film is relentless. Not once are we allowed to think that maybe, just maybe, this is all just a momentary scare that can be easily escaped. Even as Sally Hardesty finally breaks free of Leatherface and rides off in the back of a pickup truck, we cannot be sure that she is safe. She is clearly disturbed by her ordeal, manically screaming and laughing and covered in the blood of those who were not as lucky. And as we learned earlier in the film, who can really be trusted in this isolated backwoods area?

The gas station attendant was in on it, and everyone else that may have helped was likely far away—or already a victim. Is Sally simply meant to meet her fate elsewhere? As the credits roll, little is revealed about why all of this has occurred. I am unable to even begin to understand how Leatherface and his family became that disturbed, or why they felt a need to commit such aggression against annoying yet otherwise harmless and innocent victims. My questions remain unanswered as I try to find my bearings upon turning away from the screen a final time. I’m not sure how I can really begin to process it all.

Détente.

In reliving brief segments of my previous experience, I still find myself unhinged by The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. If I wanted to feel better, or at least resolve some of my unanswered questions, I could view the inferior sequels and prequels, read books on serial killers or the psychology of fear, or maybe even rationalize every cut, sound, and angle from a filmmaking perspective by reading a book on that subject. I could put myself at ease very quickly, but then what is the fun in that?

A good horror movie is supposed to be unsettling and play into our worst fears. Through this film, Tobe Hooper did just that. Watching The Texas Chainsaw Massacre has brought me closer to what my cynical self never experienced before: what the horror movie experience must be like for others. I don’t want the mystery to be ruined. I don’t want answers. I’m just happy that I have finally found a horror movie that helps me realize the true impact this unique genre can have.

Pages: 1 2

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.