Cherchez La Femme: My Affair with The Black Dahlia

Published on September 29th, 2008 in: Books, Halloween, Horror, Issues, Movies, True Crime |The Black Dahlia was the first James Ellroy novel I read and I loved it. I had become a fan of the hardboiled detective fiction genre after being introduced to the pulp novels of Jim Thompson in a Film Noir class. Then, seeking more books in that vein, I soon devoured all the books of Raymond Chandler and James M. Cain. Since Thompson, Chandler, and Cain were all deceased, I was thrilled that Ellroy was still alive and kicking.

But it was more than that.

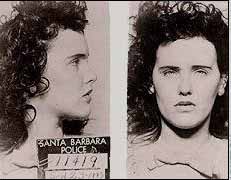

Elizabeth Short, aka “The Black Dahlia”

The grotesque nature of the crime, the beauty of the victim, and the unbelievable fact that Elizabeth Short’s murder had never been solved haunted me. I wanted Ellroy’s resolution to be true, though I assumed that the real story was probably much less complex and fantastic.

As an Ellroy fan, I thought Curtis Hansen’s 1997 film adaptation of L.A. Confidential was note-perfect. Although some of the plot points had been excised to meet the cinematic demands of brevity and clarity, I didn’t mind a bit.

In 1999, I read author John Gilmore’s take on the murder: Severed: The True Story of The Black Dahlia. Gilmore’s father was an LAPD officer at the time the crime was committed, though he was not directly involved with the case. Besides the incredibly gruesome, never-before-seen crime and autopsy photos, Gilmore’s prose disturbed me.

His hypothesis—that an “alcoholic drifter” named Jack Anderson Wilson committed the crime—seemed plausible, since according to Gilmore, Wilson knew specific details about the crime that would only be known to the killer or an accomplice. This information was related directly to Gilmore by Wilson in 1982. Wilson died in a fire a few days after his interview with Gilmore, thus erasing any possibilities of charging him with the murder.

Not long after, rumors that director David Fincher was handling the film adaptation of The Black Dahlia began to bubble forth. I figured one Ellroy film was enough for Curtis Hansen and since I loved Fincher’s creepy, twisted The Game (released one week before L.A. Confidential, in fact), I felt he’d be ideal to handle The Black Dahlia.

But as we all know, in Hollywood, things are never what they appear to be. Eventually, the project was passed off to Brian De Palma, who I’ve long dismissed as a rip-off artist and a hack. The casting of Josh Hartnett as Dwight “Bucky” Bleichert didn’t give me any additional confidence in De Palma’s skills.

Still, Elizabeth Short remained in my subconscious. Eventually, the idea of dressing as the Black Dahlia for Halloween, complete with 1940s style hair and attire, took hold of me. I found a re-issued Vogue pattern of a 1940s dress and kept my eyes peeled for the appropriate fabric. Since it had been over 15 years since I’d read Ellroy’s book, I decided to re-read it. Then, I watched De Palma’s movie version.

Mia Kirshner as

The Black Dahlia

The film begins auspiciously enough, with entire scenes lifted from the novel. Yet, by removing certain pieces of key exposition—specifically, the disappearance of Sergeant Lee Blanchard’s sister—his motivation for obsession ring hollow. Furthermore, there is very little which reveals that Bleichert was the more obsessed of the two, a point upon which the entire novel hinges.

Like Lee and Bucky, I was also hooked on The Black Dahlia. I did some Internet searching and found author Pamela Hazleton’s Black Dahlia Website. She provides an overview of the case as well as the books written on it. I was surprised to see just how many other books had been written proposing theories of the murder. I decided to explore retired LAPD detective Steve Hodel’s account of the case in his book, The Black Dahlia Avenger, mainly because James Ellroy himself supports his theories.

Wisely, Hodel begins with details on his exemplary record while a police officer and describes how he spent many of those years as a Homicide detective with a high “solve rate” in the 300 murders to which he was assigned. After the death of his father in 1999, Hodel found two photos found in his father’s personal effects which he felt certain were Elizabeth Short. Eventually, he came to the conclusion that his father, Dr. George Hill Hodel, had committed the Black Dahlia murder.

I recalled seeing these photos on an episode of 48 Hours in 2004. At that time, I didn’t believe the woman in the photos was Short and dismissed Hodel’s theories. Despite Hodel’s credible background, I remained skeptical as I read the book. By the time I reached the end, however, I became convinced that his father, Dr. Hodel, was not only responsible for the murder of Elizabeth Short, but at least three other women from a list of 31 unsolved homicides from the years between 1943 and 1950.

This is not because of the photos. And it’s not because of the foreword to the book, written by James Ellroy, who himself reviewed years of newspaper articles and public documents when writing his fictionalized novel. Ellroy flat-out says that Hodel has solved the crime, despite not believing those two photographs are of Short.

I have been convinced by Hodel’s years of painstaking, meticulous research and his in-depth analysis of not only the official Elizabeth Short files from LAPD, but secret files that were “sanitized” by the force to cover up years of corruption and scandal. And, despite my long-held beliefs, the real story is both complex and fantastic.

Now looking back at Gilmore’s book, I realize how shoddy his “investigative techniques” were. The book is captivating, but it reads more like fiction than a true crime exposé. Unlike Hodel’s book, there are no footnotes, endnotes, or works cited. There is no verifiable proof that Gilmore even reviewed the police files.

Although I believe Hodel’s theory, here are some of the others:

The Black Dahlia Solution website is operated by someone who claims to have “spent 30 years working for the US Government as a mathematician” and who “garnered considerable experience in decryption.” This unidentified person claims to have “decrypted” the letters that were sent to newspapers and police in 1947 by someone calling themselves the “Black Dahlia Avenger.” The site is written in a rambling, confusing style and it is difficult to determine who is being accused of the murder, although someone named “Ed Burns” seems to be the site owner’s prime suspect.

Janice Knowlton (Daddy Was The Black Dahlia Killer), who speculated that her own father, George Knowlton committed the crime, based her theory on “repressed memories” which surfaced in the therapy she received to recover from an abusive childhood. While I don’t doubt the veracity of her abuse claims, such “repressed memories” have long been considered questionable by respected members of the mental health profession. Additionally, Knowlton’s vulgar and vicious missives to Pamela Hazelton destroy her reliability and convey her compromised mental and emotional state in the years before her suicide in 2004.

Mary Pacios, a childhood friend of Short’s who wrote about the murder in her book Childhood Shadows, throws Orson Welles into the list of suspects. On her Black Dahlia Info website she also provides a not-so-subtle commentary on her opinion of Hodel’s theory, by quoting Sgt. John St. John of the LAPD: “”It is amazing how many people offer up a relative as the killer.” However, Pacios only provides synopses of excerpts of the official documents and there is nothing which shows she has reviewed the complete LAPD files.

Donald H. Wolfe, author of The Black Dahlia Files, builds upon much of the information presented in Gilmore’s book and proposes that several people were involved with the Short murder: Norman Chandler, publisher of the Los Angeles Times; West Coast gangster Bugsy Siegel; mobsters Albert Greenberg and Maurice Clement; abortion doctor Dr. Leslie C. Audrain; and the same Jack Anderson Wilson named in Gilmore’s book. He provides fairly compelling evidence of their involvement, convinced that the “key question” kept secret by the LAPD all these years was that Short was pregnant with Chandler’s child and that she was killed because of this.

Wolfe further attempts to debunk Hodel’s theory using twelve “exhibits;” however, several of these do not successfully discount Hodel’s theories and actually misrepresent his claims. Additionally, even if some of Wolfe’s “exhibits” proved true, they are not pieces of circumstantial evidence that would remove Dr. Hodel as a suspect. The most damning evidence against Wolfe’s theory is the coroner’s report that Short was not pregnant at the time of her murder. There is no evidence in any documentation to support this pregnancy.

Larry Harnisch, writer for the L.A. Times and a close friend of LAPD Detective Brian Carr (who inherited the Dahlia case from his predecessor), proposed his own theories on his Heaven Is Here website, speculating that a Dr. Walter A. Bayley was the murderer. Harnisch tries to discredit Hodel but admits he hasn’t even read his entire book. Harnisch has also publicly insulted Hodel and John Gilmore. Such behavior, accompanied by a distinct lack of proof, render his theory pretty flimsy.

When I started reading Hodel’s book, I was concerned that he was just trying to exact vengeance on his father, who, by all accounts, was a cold, cruel, abusive, and sadistic man. However, he genuinely seems to care about solving the case.

Unlike the Dahlia theorists who attack each other with shameful displays of self-aggrandizement, Hodel does not get into what he calls “pissing contests.” His refusal to play dirty lends him enormous credibility. He is also human enough to admit that some of the LAPD officers he idolized when he was on the force were not as perfect as he imagined and probably played a role in covering up important information about the case.

Hodel’s investigation is ongoing and he continues to provide meticulous updates on his website. He even admits when his theories have been proven incorrect. A revelation that one of the photos from his father’s album (believed to be Short) was in fact an actress named Marya Marcos has been added to the extensive FAQ section on his website. Perhaps his discovery of the photos was serendipitous in that it eventually led him to the truth about his father’s dark past as well as the murder itself.

Ellroy’s book and DePalma’s movie version give us bits and pieces of the real Elizabeth Short but mostly provide fantasy fodder. And still, she eludes us. From the LAPD cover-up to the continued infighting amongst Dahlia theorists to the murder itself, it seems that Elizabeth Short was used and abused in both life and death. It’s easy to get lost in the mystery of the Black Dahlia and forget why we have become fascinated with her in the first place: she was the victim of a vicious murderer.

Ironically, it’s an early investigative report from the D.A.’s file—when she was still a “Jane Doe”—which reminds me that Elizabeth Short was a human being.

. . . description being as follows: age interminable, young; ht 5″3′; weight 118#; all fingernails down to the quick; no bunions on feet; hair shaved on legs below the knees; hair shaved under arms; grayish green eyes; narrow, small nose, uptipped slightly; small upper lip; vaccination scar left leg between knee and thigh; small scar above left knee; 1″ in length scar about 1 ½ inches to right of navel; brown hair, indication of being hennaed. . .

It was eventually discovered that this “Jane Doe” was Elizabeth Short, born July 29, 1924. My birth date is July 28, which makes Short a Leo like me. Physically, we were remarkably similar in height, weight, eye color, and hair color.

I don’t know if these similarities are why I’ve been fascinated with her all these years. To be honest, I didn’t know most of these details until now. Perhaps my fascination with Elizabeth Short is the result of my image of her: the most heartbreaking example of a small-town girl being crushed by Hollywood, the ultimate victim of a city in which nothing, not even murder, is what it appears to be.

Additional Resources:

For more on Steve Hodel’s theory, please visit The Black Dahlia Avenger website.

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.