No Sense Makes Sense: Peter Bogdanovich’s Targets

Published on January 30th, 2008 in: Issues, Movie Reviews, Movies, Retrovirus, Underground/Cult |By Less Lee Moore

“My father is the jailhouse. My father is your system… I am only what you made me. I am only a reflection of you.”

—From the testimony of Charles Manson in the Tate-LaBianca murder trial, November 20, 1970

The thrill that’ll getcha

when you get your picture…

Targets was filmed in April 1967, but its release was delayed to August 1968 because director Peter Bogdanovich couldn’t find a distributor and because Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy were assassinated the next year. Paramount Pictures felt there were too many real-life deaths confronting Americans to justify putting Targets in front of audiences. These two deaths were not the only ones to affect the film.

Student protests of the Vietnam War began in 1963, although the U.S. bombing and subsequent deployment of troops didn’t begin until March 1965. Within a year of U.S. entrance into the war, Gallup indicated that 41% of pollsters thought the government was doing a good job, as opposed to 48% the previous year. (1)

On July 14, 1966, alcoholic high-school dropout Richard Speck murdered eight student nurses in Chicago, Illinois. Speck, who attempted suicide in the hotel where he’d been hiding out, was brought to a hospital, where a doctor recognized his “Born To Raise Hell” tattoo from news reports and called the police. (2)

The most significant event affecting Targets took place on August 1, 1966, when University of Texas student Charles Whitman murdered his wife and mother, and then, from the top of the observation deck of the University’s Main Building, shot and killed 14 people and wounded 31 others before being gunned down by Austin police. (3)

Charles Whitman on the

cover of Time, August 1966

It was this deadly rampage that inspired Targets. This and the fact that film legend Boris Karloff owed horror movie director Roger Corman two days of shooting time and Corman serendipitously bequeathed the proceeds of this debt on to Peter Bogdanovich.

Targets is not a horror movie although it depicts horror in the face of senseless violence. Other acclaimed films of the time, like Bonnie and Clyde, delight in orgies of bloody excess. The horror we experience in Targets is not gratuitous but is still a reflection of the times, including Hollywood itself.

The land of pretend was experiencing genuine upheaval through the disintegration of the studio system and the Hays Code, both of which had dominated since the late 1920s. Targets explores the conflict between old and new Hollywood through the characters of Byron Orlock and Sammy Michaels. Both are representations of the actors who portray them. Boris Karloff plays Orlock, an aging star who thinks he’s a relic among modern movies. Bogdanovich plays Michaels, a writer-director who wants to resuscitate Orlock’s career as Orlock himself is trying to end it.

Michaels is an embodiment of the new era of filmmaking but, like Bogdanovich, he’s in love with the old days. In one scene, we watch Orlok and Michaels watching Howard Hawks’ The Criminal Code on late-night TV, a movie starring Karloff as the heavy.

Michaels looks depressed and says, “All of the good movies have been made.” In the DVD commentary Bogdanovich admits this line of dialogue was adlibbed, but laughs and says that’s how he felt at the time and in fact, still does. Additionally, the Hawks scene foreshadows the climax of Targets: a confrontation between Orlok and antagonist Bobby Thompson. In doing this, Targets blurs the line between fantasy and reality, a motif that continues throughout the film.

Bobby Thompson

Orlok thinks people see him as old-fashioned but he represents a current threat to Bobby, although it is a symbolic one. Bobby, a young Vietnam veteran, develops an obsession with Orlok, who he perceives as a representation of his father. Early in the film, Bobby buys a rifle at a gun shop across the street from the film studio where Orlok is talking to Sammy. A point-of-view shot shows Orlok in the crosshairs of the gun. Later, Bobby and his father (whom he only addresses as “Sir”) are picking off tin cans at the shooting range and Bobby aims at him. Another crosshair point-of-view shot follows and although Bobby’s father yells at him, Bobby can’t help but smirk.

Bobby’s rage against his father is repressed, but is made manifest when he shoots and kills his wife and mother, then embarks on a shooting spree from the California freeway to a drive-in movie theatre, the same one where Orlok is appearing for the premier of his last film (another Karloff film, The Terror, directed by Roger Corman). Bobby runs out of ammunition and is apprehended, but not before Orlok confronts him.

Orlok, wearing a tuxedo, approaches Thompson at the drive-in theatre as his character in The Terror (also in a tuxedo) approaches the side of the screen. In a fit of confused fury, Thompson fires at the movie screen, conflating Orlok the person with Orlok the monster.

Critic Lawrence Russell, praises Targets but says such “meta-criticism leads to the over-rating of such films.” He suggests audiences will “groan when a playwright comes up with yet another play about the theatre. . .,” but in film such “maneuvers are usually greeted as being extremely hip.” He speculates that this “imitation of an imitation” may be the “signature of the postmodern disease.” (4)

Metacriticism is the hallmark of postmodern theory, but Targets is original and imaginative because it quotes its predecessors. Bogdanovich is a cinephile who doesn’t want the past to be forgotten, just as his character, Sammy, doesn’t want Byron Orlock to leave Hollywood. Bogdanovich’s love of cinema is obvious and admirable.

Although there is little violence, the film explodes in a riot of color, which Bogdanovich claims was director George Cukor’s influence. Production designer Polly Platt’s inventiveness is clear from the symbolism of the hues used to depict the two main characters. Scenes with Orlok feature warm colors, such as pinks, browns, yellows, and beiges. Conversely, Thompson’s environment is always blue, white, grey, and black. This has a subtle, yet marked effect.

Byron Orlock and Sammy Michaels

Bogdanovich says he didn’t use a score because he wanted to tell the story visually, adding that there is “no reason to use music to tell you what to feel.” Music has been used to accompany films since the heyday of the silent period, when pipe organs were installed in most first-class theaters. However, many modern directors (Sofia Coppola, Wes Anderson, Cameron Crowe), often dispense with credible plots or acting, instead trying to affect audience emotions through the use of popular songs.

Conversely, the sound in Targets is as naturalistic as a documentary. The best example of this is in the sniper sequence from the water tower, but as Bogdanovich notes, they couldn’t afford a sound crew, so those scenes were shot in silent, with sound effects being added in post-production. It’s a testament to the extraordinary skills of sound editor Verna Fields, who used 28 different tracks to create this realism.

This realism continues in the cinematography: none of the driving scenes use rear projection and all were shot on the California freeways, despite that being illegal at the time. Bogdanovich jokes that this is a lesson from the “Roger Corman School of Guerrilla Filmmaking.” He also seems to have learned that economy may be dictated by budget, but with ingenuity, it can lead to exceptionally riveting films. Lazlo Kovacs, the director of photography, used natural light throughout the film, which adds to the sense of real and impending doom, particularly the drive-in scenes which are as murky as ink.

Bogdanovich filmed the two gun shop scenes from the movie in actual gun shops. In order to do this the crew told the employees they were filming a movie about a guy hunting with his father. Interestingly, this was the same ruse Charles Whitman used.

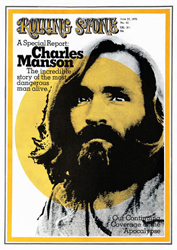

Time Magazine reported that on the morning of August 1, Whitman told a clerk in a hardware store that he was purchasing ammunition to “shoot some pigs.” (5) Targets amends the line to “gonna shoot some pigs.” It’s a startling and unintentional foreshadowing of the Tate-LaBianca murders committed by members of the Manson Family in August of 1969.

Although the word “pigs” had been used to describe police officers since the 19th century, Charles Manson intercepted another vibe from the Beatles song “Piggies.” George Harrison intended the song to be a commentary on upper-class greed, but Manson saw his victims as “pigs” because he thought his Family members were the outcasts that society created and then refused to take care of.

Norman Bates

Similarly, Thompson is depicted as an outcast in his own life, someone who goes horribly wrong, much like Norman Bates in Psycho only not confined to the Bates Motel. This is an effective metaphor for the late sixties.

But what did go wrong? What is most disturbing about Targets is that we are not given any solid answers, only speculations that don’t necessarily make sense.

And if sense makes no sense, then it follows that, as Manson himself was fond of saying, “no sense makes sense.”

Sources:

1. Wikipedia, “Opposition to the Vietnam War.”

2. Wikipedia, “Richard Speck.”

3. Wikipedia, “Charles Whitman.”

4. Lawrence Russell, “Targets,” Culture Court. July 2003.

5. “The Madman in the Tower,” Time Magazine. August 12, 1966.

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.