Cure for Pain: The Mark Sandman Story

Published on July 17th, 2012 in: Current Faves, Documentaries, DVD, Movie Reviews, Movies, Music, Reviews |By Chelsea Spear

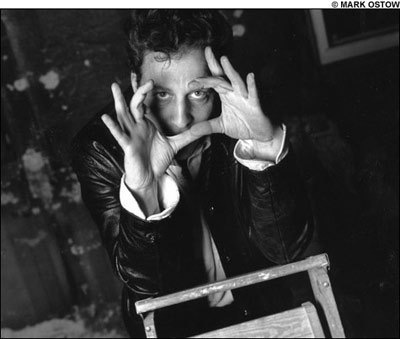

Photo © Mark Ostow

Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, Mark Sandman cut a wide swath through the Boston music scene. His first band, Treat Her Right, scored a local radio hit with the deadpan, eerie single “I Think She Likes Me.” The various bands with whom Sandman played—most notably Supergroup, Candybar, and Morphine—played two sets a night at the shoebox-shaped bar Plough and Stars. Even as Morphine ascended to a renowned trio with a devoted following, Sandman could be found playing at the annual Central Square World’s Fair, talking with elementary school classes about his handmade musical instruments, converting his loft apartment into a recording studio, or just hanging out in the back booth at the Middle East nightclub. His sudden, tragic death in Italy in 1999 left a huge hole, both in the music world where he made his mark, and within the Boston arts community.

Morphine’s cinematic sound and spare arrangements—based around drums, a two-string bass of Sandman’s own creation, two saxophones played simultaneously, and Sandman’s Robert Mitchum-esque basso profundo—allowed them to stand out from their grungy peers of the alternative era. Sandman also cultivated a kind of mystique that countered the confessional tones many of his fellow travelers struck. He rarely talked about himself and his life, and would rattle off baseball scores or start quoting crime novels to prying reporters. Twelve years after his death, filmmakers Robert Balver and David Ferino re-open the book on Sandman with their documentary Cure for Pain.

Though the film draws from interviews with those who were closest to Sandman—his parents, his older sister, and his girlfriend Sabine—the directors steer clear of weepy Behind the Music-style confessionals or other histrionics. Both of Sandman’s older brothers died in their youth, and this combined with Sandman’s premature death give his story an undeniably tragic quality. Through some canny edits and images culled from mother Guitelle Sandman’s book Four Minus Three: A Mother’s Story, Balver and Ferino point towards the autobiographical points of departure for Sandman’s work.

Interviews with various musicians place Morphine’s albums in a greater context. Mike Watt’s observations about Sandman’s minimal production and bass playing make the music theory behind Sandman’s approach accessible to the layman with charm and good humor. Likewise, an interview with the Presidents of the United States of America frontman Chris Ballew shows a friendly, generous side of Sandman that few may have seen. While these talking heads touch upon Sandman’s better qualities, Balver and Ferino speak with associates who saw a different side of him. Producer Paul Q. Kolderie spoke of Sandman’s violently mercurial side, while Jerome Dupree’s account of his dismissal from the first lineup of Morphine shows how mercenary Sandman could be.

A black title screen simply reading “Palestrina, 1999” may stir up a sense of dread among those who know of the circumstances of Sandman’s death and of his final resting place. (Indeed, a few choked sobs rang out at this point in the film when I saw it at the Brattle.) While descriptions of the high altitude and thick humidity on the night of his death give the third act a sense of foreboding, the filmmakers don’t milk the musician’s untimely onstage death as a moment of high drama. (A recording of Sandman’s musical multitasking during Morphine’s soundcheck limns this portion with surprising wit.) The aftermath of Sandman’s death has an offhand tragedy that might give viewers a lump in the throat.

As a Boston music aficionado, and someone who was on the periphery of the scene at this time, I felt a little disappointed that the filmmakers didn’t focus as much on Sandman’s role as the unofficial mayor of Central Square. I would have liked to hear the insights of Accurate Records owner Russ Gershon, who released the first Morphine album, or with Willie “Loco” Alexander, the Boston punk legend who sang “Mr. Sandman” at a memorial for the fallen singer. Additionally, Sandman’s work with schoolchildren and his appearances at Cambridge-area grammar schools are an unsung element of his work, and I would have been curious to see or hear more about his ersatz forays into music education.

The film has an appealingly handmade look that might play better on the small screen. The janky VHS dubs and compressed clips that seem to have been ripped from YouTube caused me to feel some seasickness when I caught a screening of this. At times, the directors’ skills at framing their subjects undermine what their interviewees have to say. One interview with Morphine manager Deb Klein is marred by a timecode running through the bottom of the screen. Another interview with Sandman’s widow Sabine places her to the extreme left of the frame with little reason. The collage-like elements of the film make it look less like a polished biographical tome than like a scrapbook, and has a lived-in feel that Sandman would appreciate.

Fans of Morphine and Treat Her Right would do well to check out Cure for Pain. Casual fans or those who are curious about Sandman’s status as one of the most innovative musicians of the Alternative Nation era would also find this edifying. Balver and Ferino do a great job of contextualizing Sandman’s body of work, and their choice live clips will leave new fans hungry for more.

Cure For Pain was directed by Robert Balver and David Ferino and released by Gatling Pictures. The film is available in a two-disc collector’s edition from the Gatling Pictures website.

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.