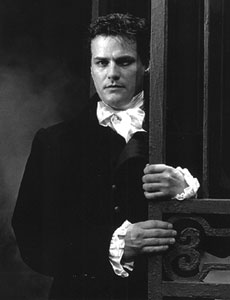

Paul Gross in the Performance of My Lifetime

Published on May 30th, 2012 in: Canadian Content, Issues, True Patriot Love |By Michelle Patterson

Paul Gross wasn’t about to change just my perceptions of what makes good Art good (the kind with a capital “A”) and what makes bad art bad (the kind that makes you wince at the attempt of it in the first place). “Why aren’t these people afraid of failure,” I’d think to myself. “What made them think that they could do this?”

Paul Gross was about to go forth and change my world. My world, which consisted mainly of pop culture, and the question of what exactly made someone better than her peers. I just knew what was well-done and what could be sneered at, derisively. I had some large blinders when it came to the embodiment of pop culture’s vast history. It was equal parts black and white cinema, cheeky literature, and weird photography; it was what constituted the freaks at the back of the classroom and the introverted girl in the corner, her nose buried in a book. Everything outside of that wasn’t something I wanted to bother with because it was probably boring.

Probably boring? Then again, I didn’t have a clue if it was boring or not because I didn’t allow myself the chance to experience it. I couldn’t be over anything I hadn’t seen, heard, or felt. Blame my youth and the whiplash I gave myself from bending so far away from one type of Art to another. At that point, the theater was not it for me. I’d met so-called “theater geeks” at the first college I attended and wasn’t impressed with the excessive snobbery and the overly earnest attempt to be different from everyone else (imagine my surprise when later in life, I met “film geeks” at a highly-esteemed liberal arts college and the difference between the two groups was truly night and dusk).

The one true strength that theater has over all other types of Art is the overall experience, as a collective. Of course, you can experience a film, but the figures aren’t trying to connect with you and get you to notice that those words they’re saying? They’re speaking in such a way because of something significant. They want you to know the why, what, and who behind the words. Films dictate the experience, they don’t ask for your input and respect. With theater, the people onstage want you to all be keyed into that singular thing which cannot be named, but is there: a transcendent moment in time when the audience breathes the same breath. That is a big difference, kids, and one I was privileged to see in the long past.

I knew of him, but didn’t really experience the depth of Paul Gross’s talent until I was a member of the audience at Canada’s Stratford (Shakespeare) festival, which included his sole performance of Hamlet. It was my first awareness of what a person’s take on a role could really do to the whole lot of a play. I hope that most of us have read Hamlet, and taken it to be the grandmother of all plays, the one that we’re sure to remember for the rest of history as the greatest that ever was, no?

Yes, it was something to read and appreciate; like most classic words of Art it was there merely to react to—and not in any emotional way—not because there was nothing emotional for me to “get,” but because I didn’t fully understand it. Once I was told a work of eminent literature is where it all began, it was slightly out of reach for me to wholly comprehend in a way that was meaningful to me.

I’d only ever seen the film adaptations of Hamlet and those were a complete snooze. Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet was pervy and much too stiff to appreciate. Mel Gibson’s overwrought and frantic performance was just a hint at how extreme he wished to take it, while Kenneth Branagh’s serious posing was overshadowed by almost every other actor in his version. Seeing this particular Hamlet in person was one thing, seeing the connection between actor and play was another.

There is something to be said about the power of laughter. If you can get an audience rolling in the aisles, you can get them to do anything—even cry. Gross’s Hamlet was undeniably kinetic, only this time there was an ever-present threat that he’d collapse into mad giggles. His Hamlet was annoyed at the state of things, yes, but also underlining everything with a giant Vincent Price-shaped wink which started to create this sense of unease in the people around me. The laughter at first was nervous and unsure, mostly confused murmurs. He was a sarcastic, snarky, and charming bastard; he was plugged into a sweaty undercurrent of unflagging enthusiasm for what he was performing, for the words he got to speak.

As the moments like this piled one on top of the other, over and over again, soon the laughter from the crowd turned to absolute glee. I’d suspected that Hamlet was amusing; Shakespeare was always pretty witty to me. Only this Hamlet was hysterically funny! We were howling and holding on to each other, gasping for breath, when it happened. Suddenly, Hamlet was broken down like an alcoholic the day after a bender, bitter at his fate in life. It was a shocking transition. From that moment on, we all fell silent and I honestly felt linked to every single person in that theater. We were a part of this Hamlet in this theater.

Thanks to Paul Gross, I understood what the power of this type of Art could do and how it was the best shared experience I’d ever had. I share this story with people to prove that I found the most complete Artistic experience of my life in a distinguished, yet unstuffy theater in Stratford, Ontario. We were all here for different reasons. Most of all, I was here to see if I had learned and experienced enough to find my definitive Shakespeare. Through one performance, I made that discovery and beyond a doubt, had my own Art of the theater to remember.

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.