Valerie Solanas: Who Shot Andy Warhol?

Published on January 30th, 2012 in: Art, Books, Feminism, Issues, LGBTQ, Movies, Oh No You Didn't |In June of 1968, a woman named Valerie Solanas rode the elevator up to The Factory, Andy Warhol’s loft. In the elevator with her was Andy Warhol himself. In the Factory’s office was Mario Amaya, an art editor from London; Fred Hughes, one of Warhol’s assistants; and Paul Morrissey, Warhol’s executive producer. Morrissey walked into the bathroom. Within a few minutes, Solanas pulled out a .32 caliber gun and shot Warhol three times. She then shot Amaya in the hip. Hughes begged her to stop. When she fired the gun at him, it jammed. Just then, the elevator doors opened and Hughes told her get on. So she did.

Screencap from I Shot Andy Warhol, 1996

Soon after, Valerie turned herself in to police. When questioned by the media outside of the police station, Valerie said that her reasons for shooting Warhol were “very involved. Read my manifesto and it will tell you what I am.” Solanas served a three-year sentence for attempted murder and died in 1988.

Over 40 years have passed since the shooting, but people are still asking the question “Why?”

The manifesto in question was the SCUM Manifesto, a 21-page document outlining Solanas’s ideas on not only the inferiority of the male gender, but her ideas on eliminating it altogether. But the Manifesto wasn’t created in a vacuum; perhaps the more significant question is, “Who was Valerie Solanas?”

The website Womynkind provides a detailed biography of Solanas, but without any sources cited (and a plethora of typos), it’s difficult to know how much of it is true. A brief, but somewhat more credible account, comes via a Village Voice review of Solanas’s play Up Your Ass from 2000. The play’s director George Coates, sent his assistant director, “Eddy Falconer to talk with Valerie’s sister, Judith, who described the underpinnings of the rage Solanas turned into Lenny Bruce-style satire, including sexual abuse by her father as a small child; the birth of a son at age 15, fathered by a married man (the child was taken away, never to be seen again); her year in a mental hospital in Florida; her struggles, on and off medication, to write.”

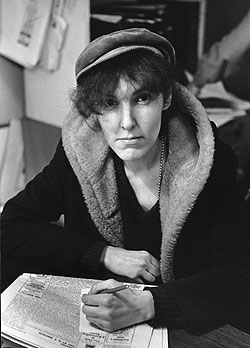

Valerie Solanas, February 1967

Photo © Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images

What’s interesting is how almost every online article I could find about Valerie Solanas mentions little biographical information but a wide range of speculative theories and categorical terms. Wikipedia’s entry refers to her as “an American radical feminist writer,” that writing being, of course, the SCUM Manifesto itself; the play, Up Your Ass; and a “A Young Girl’s Primer,” described as “non-fictional article reprinted from Cavalier magazine 1966.”

A review of the Manifesto calls Solanas “a lesbian drifter, psychotic, and would-be writer” while a 2004 reprint of the Manifesto says that the work itself was considered “certifiably crazy” at the time of its 1968 publication (which took place after the shooting).

In 2009, playwright Margo Feiden revealed to The New York Times and Interview magazine (the latter founded by Andy Warhol in 1969) that Solanas had actually confronted her outside of her home—the same day she shot Warhol—in an attempt to get Feiden to produce a play for her. She says Solanas told her, “I’m going now to shoot Andy Warhol and that will make me famous, and that will make the play famous, and you will produce it. You will.”

Feiden says she never told the story to anyone for 40 years, even though on June 3, 1968 she called the police to report Solanas’s promise. In the Interview piece, she also tells writer Glenn O’Brien (himself a former member of The Factory), about three articles she read which made “obvious to me that people think that Andy Warhol lost the play or wouldn’t give it back, and that was in some way mediating her horrific act.” She continues:

FEIDEN: But, in fact, she did that shooting as a publicity stunt to be famous, so that I would produce her play. Why should Andy Warhol’s name, in any way, be sullied? Why should people think that she had any justification for what she did? He gave her none.

O’BRIEN: That’s what upset me about that film, I Shot Andy Warhol [1996]. I knew the woman who made that film, and I felt that it was really unconscionable and exploitative, that it represented that she had some justification, when obviously there was none.

Mary Harron’s film does present the events before Solanas shot Warhol, beginning with the shooting itself and then backtracking briefly to the late 1950s, when Solanas graduated from the University of Maryland at College Park with a degree in psychology and a membership in the Psi Chi honor society. Writer Dana Heller describes Harron’s film as “painstakingly researched, meticulously detailed” yet a “partially imagined account of the events.” Such seemingly contradictory opinions of the film seem to reflect the contradictory opinions of Solanas herself. Was she a crazy genius or just crazy?

Screencap from I Shot Andy Warhol, 1996

In I Shot Andy Warhol, Solanas is portrayed—wonderfully—by actress Lili Taylor and although she comes across as confrontational, one senses that she’s got something important to say, if only people would listen. Wisely, Harron intercuts narrative scenes with black and white, single camera shots of Taylor-as-Solanas reading directly from the SCUM Manifesto. While reading the Manifesto (which you can do here) proves a bit of a challenge—it is a dense, sometimes confusing text—the excerpts convey that it’s not just the scribbling of a madwoman. The first paragraph is no more outlandish than Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal, which suggests the way to help the starving poor in Ireland is to feed them children.It is incendiary yet darkly hilarious:

“Life in this society being, at best, an utter bore and no aspect of society being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and destroy the male sex.”

There are other sections of the Manifesto, however, which seem not only relevant but totally straightforward. Solanas remarks that the male tries to convince himself and women:

“. . . that the female function is to bear and raise children and to relax, comfort and boost the ego if the male; that her function is such as to make her interchangeable with every other female. In actual fact, the female function is to relate, groove, love and be herself, irreplaceable by anyone else; the male function is to produce sperm. We now have sperm banks.

“In actual fact, the female function is to explore, discover, invent, solve problems crack jokes, make music—all with love. In other words, create a magic world.”

It seems shameful that someone with this much to say has been demonized by both men and women. This is not to say that shooting Andy Warhol was somehow justified and without serious consequences. A Richard Avedon photo clearly shows the extent of Warhol’s injuries and the impact upon his life was immeasurable. He was forever changed emotionally and continued to have health problems up until his death in 1987 following gall bladder surgery.

Yet this should not mitigate the value of Solanas’s written words, however problematic, revolutionary, and violent they may be. Despite Feiden’s self-centered handwringing about keeping her secret for four decades, Harron’s film doesn’t pin the blame for Warhol’s shooting on the artist himself. Instead, it portrays Solanas as a woman on the verge. It’s not the possiblity that Warhol lost her play or refused to produce it that caused the shooting, it’s that by all accounts Solanas had a rough life plagued by sexual abuse and mental illness, both of which not only informed her inflammatory writing but also contributed to her eventual decline into homicidal madness. It could have been anything that set her off; unfortunately, it happened to be Warhol.

I Shot Andy Warhol presents Valerie Solanas as an outsider, but it presents Warhol as one, too. There is a scene in the middle section of the film—a Factory party in which Solanas wanders around the fringes of the beautiful inhabitants of the It Crowd—where Solanas and Warhol catch each other’s eyes and seem to share a moment of Otherness. It is this fictional image which remains with me along with the undeniable reality of Valerie Solanas’s words.

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.