It’s a Love/Hate Thing: Why Dollhouse‘s Echo Matters

Published on March 30th, 2011 in: Back Off Man I'm A Feminist, Feminism, Issues, Science Fiction, TV |By Catherine Coker

We hate Echo.

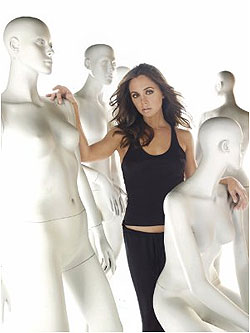

Well, many of us do. Because she’s played by Eliza Dushku (who we didn’t have a problem with as Faith, or as Buffy in Faith’s body, come to think of it), or because she is so very much a FOX network construct (iddy-biddy dress and shiny red motorcycle), or because she’s really the misogynist wet dream Joss Whedon never dared to have otherwise (Yeah, I’ve got nothing on that one; anti-Whedonists are a class all their own). When Dollhouse was canceled, the anger wasn’t at television executives it was at Echo.

Why?

Because we’re afraid of her. She is what we all fear ourselves to be: An empty vessel, programmed by the wants and desires of those around us, leaving behind a vaguely curious, half-formed entity buffeted about by those more powerful than she. (And if you’ve ever watched anything by Joss Whedon, then you know that It’s All About Power.) She is more Advertising than Education, the Effect and not the Cause. She is passive; she is consumed.

She is what every science fiction novel warned you about. And yes, this does include the Girls of Planet 5, because:

She fights back.

Her brain is as beautiful and resilient as that frequently displayed body of hers. Despite being caught between corporations and governments, scientists and hackers, dubious father figures and would-be lovers, she holds onto the kernel of self that is all her own. She nurtures it through constant struggle and defeat, even through one of the bitterest victories ever played on television outside of a war documentary.

Echo is what we fear we could become, but could never truly be.

You see, if we were kept in a place where we were fed and clothed, petted and amused, would we fight back? If we knew one among us was being abused by those meant to protect us, would we step up to protect her, or offer what comforts we could? Offered the choice between infantilization and growth, what would we really choose?

(The world ends with neither a whimper nor a bang, but with communications signals, and hasn’t Whedon previously proved that you Can’t Stop The Signal?)

Above all, Echo herself is an impossible thing. Yes, a thing: toy, pet, bought and paid for, consumed in toto. Remember, “when your child starts talking for the first time, you feel proud; when your dog does, you freak the hell out.”

She is not broken.

Despite being beaten, used, and abused; despite being the loneliest person you’ll ever know with over a hundred people in her head; despite being erased, rewritten, reprogrammed, and erased once more; she is not broken, and she fights back.

We hate Echo.

We love Priya and Tony; we pity Topher, who is too smart for his own good; and we are conflicted about Paul, who has all the right impulses for all the wrong reasons; we damn Boyd, for being the Father we loved of the family we never wanted; and we wonder what the hell ever happened to Dominic.

But we hate Echo.

We hate her for being an idealist in a mundane world (she wanted to take the animals home, even when though the lab wasn’t a pet shop), and for never leaving anyone behind (not even Bennett). We hate that her greatest flaws are self-righteousness in the face of corporate and government corruption and that all her own emotions never seem quite right. Most of all, we hate that in the end, romantic consummation takes place in the brain, because all our love stories tell us that that’s Not How It Goes.

Buffy may be all about power, but Echo is all about will. In a world that has no gods or demons, and where the only things that go bump in the night are distinctly and disturbingly human, she is the one who reminds us that the choice to fight back is not only ours, but is necessary.

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.