Do You Want Trombone Or Do You Want The Truth?

Published on November 29th, 2010 in: Issues, Music, Over the Gadfly's Nest, Retrovirus, Three Of A Perfect Pair |By Jimmy Ether

In the documentary Kill Your Idols, Lydia Lunch expressed her frustration with the current music scene:

“The commodification and homogenization of especially bass, guitar, and drums is the downfall of music. Where’s the fucking tuba? A trombone! Anything but a bass, guitar, and drums!”

That seems an odd statement coming from someone who very successfully used those very instruments with Teenage Jesus and the Jerks to challenge rock conventions along side bands like D.N.A., Mars, and many of the other bands from the influential New York City No Wave scene. To a certain extent, she has a point.

Guitar, bass, and drum combos have been around since well before the early days of rock and roll. They are the stock and trade of rock music and provide a somewhat limited framework. But those limitations are also what can make the combination so potent. For a group to conjure, wrangle, and wrestle anything new out of this standard format is a huge challenge—a test of musical innovation, song craft, charisma, and musicianship.

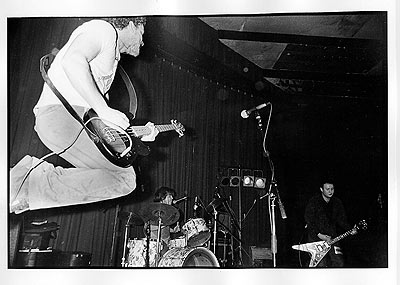

Hüsker Dü

Photo © 1987 Steve Wainstead

When it comes to utilizing the guitar, bass, and drums, there’s something especially potent about trios. While there are countless four-piece rock bands based around the magnetic signer, mysterious virtuoso guitarist, foundational bassist, and bombastic drummer, those bands almost always verge full-speed into pomposity and needlessly ornate structures: guitar solos, drums solos, vocal acrobatics, bass odysseys. With a trio, there really isn’t room for that nonsense. And even when trios do go for the solo breaks, they tend to be more compositional than histrionic. The trio format lends itself to musical economy. You find three individuals handling multiple roles and trying to make as much of an impact as they can while pushing the limitations of the format.

Trios also tend to be far more polarized than larger groups, both in musical expression and in the interaction of personalities. It’s an intimate, often volatile relationship that subsists within a delicate balance. Much like a balanced audio wire, members generally fall into their relative positions of hot, cold, and ground. The hot and cold members clash furiously together while the grounding member keeps the band hugging the road —providing just enough viscous goo to lubricate the friction.

It’s a mix of relationships illustrated by the Minutemen, Hüsker Dü, Sebadoh, and countless post-punk and indie trios. The Minutemen even took their polarity quite literally by segregating the tones of their instruments. They saw guitar and bass as sovereign states, with D. Boon’s piercing, trebly Telecaster in constant debate with Mike Watt’s melodic P-bass growl . . . and George Hurley’s tumbling beat propelling the group forward like a animated dust-cloud cat-fight.

Post-punk and indie really seem to be where trios came into their own. The minimalism and economy of the borrowed punk aesthetic lent itself well to the numeral 3: easier to travel; less gear; more money to go around making it easier to survive; and fewer egos, agendas, and issues than the larger outfits. Even on stage the trio was made to feel a minority. They had to stick together in unity against their peers, the crowd, the world. That tight-knit defensive position mixed with a desire to break out of the confines of punk and hardcore arrangements led to hundreds of innovative and influential albums and often amazingly prolific output. A good trio functioned as an unstoppable creative machine—churning out singles, EPs, albums, and double albums on the cheap in quick first-take succession.

The tried and true rock trio exists for good reason. It works. It’s efficient and flexible. It’s simple, and yet, only limited by the imagination of the artists. It impels transparency and, at its best, brutal honesty. It gives the listener full sonic impact while championing a sparsity which allows the band’s humanity to be revealed in the record grooves. You could swap out a bass with a sousaphone . . . a guitar with a trombone, but good luck making either scream. More importantly, good luck screaming your heart out while blowing into a horn.

2 Responses to “Do You Want Trombone Or Do You Want The Truth?”

November 30th, 2010 at 5:38 pm

Can’t I have both? I get so tired of the same old instruments, hence why I was an indie-obsessed teen but have now got much more into jazz, folk, classical, dance/electronica, and what is condescendingly referred to as “world music”, because I was desperate for a bit of variety. Are these not true musics also?

December 1st, 2010 at 1:14 pm

Sure. I’m a huge bebop and tropicalia fan as well as avant-pop (which is largely synth) and rap. That wasn’t the point I was trying to make, though I admit the title (a play on the Minutemen song “Do You Want New Wave Or Do You Want The Truth?”) sorta makes me seem dismissive. I’m just saying that choosing off-the-wall instrumentation doesn’t equal creativity.

Often, the oddball instrumentation becomes the novelty attraction and the songs suffer (though there are always notable exceptions). My main argument is with the idea that you can’t be innovative and influential with guitar, bass and drums. They are so common because they effective tools. If a genre or artist is boring with them, they’d be just as boring with anything else. Music is human expression through melodic craft and that transcends the orchestration. Tropicalia intrigues me not because of the instrumentation, but because of the rhythms, melodies, energy and different perspective on the world. Similarly, bebop on through to free jazz is intriguing because they screw with the concepts of melody and form. They could have just as easily done that with guitars over bass and drums as horns (and some did).

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.