Now There’s A Man Worth Going To Hell For: ‘The Devils’ And Ken Russell

Published on September 29th, 2010 in: Halloween, Horror, Movies, Underground/Cult |As part of this year’s FanExpo, Rue Morgue presented “Confessions of a Gothic Messiah: An Evening with Ken Russell” at the Bloor Cinema, a special screening of Russell’s 1971 film, The Devils, hosted by film critic Richard Crouse and attended by the director himself.

Crouse set the tone for the evening when he remarked on his own introduction into Russell’s body of work, 1975’s Tommy. He recalled his fervent desire to see the film as a teen, one which he knew would not play in his small town for months (or perhaps even ever). He hitchhiked a couple of hundred miles to the closest theater featuring a showing. Then, as soon as it was over, he bought another ticket. And then another, until he realized those couple of hundred miles were going to seem even longer on the return trip, especially when he hadn’t told anyone in his family where he was going.

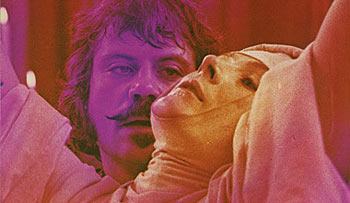

Father Urbain Grandier (Oliver Reed) and

Sister Jeanne (Vanessa Redgrave)

Such is the obsessive, addictive, and transformative power of cinema. For those of us who have experienced such fanatical devotion to certain films (in my case Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Velvet Goldmine, and Fight Club, to name just three), Crouse’s introduction made perfect sense. It was also the perfect introduction to The Devils, which is a film not easily forgotten, or in the case of its detractors, utterly loathed.

I first saw The Devils as a lowly film student of 19 or 20, but it wasn’t actually for any of my classes. My boyfriend at the time had rented it, which was a bit of surprise as he was not one for campy melodrama. I remember being absolutely horrified and hypnotized by the grotesque tableau of the movie, as well as Oliver Reed’s piercing sensuality when portraying Father Urbain Grandier, and the wicked malice of Vanessa Redgrave as Sister Jeanne.

As one who grew up Catholic, and was pious for the first third of my life, anything that evoked possession, devils, and witchcraft was particularly frightening to me (and still remains so, despite my years of agnosticism). I was the kid who worried about being too holy lest I become corrupted by a demon, as I’d read somewhere that the Devil considered it a particular victory to poison the souls of the devout. Hence my years long love/hate relationship with The Exorcist.

Yet The Devils is not a horror movie in the classic sense; the horror it conveys and evokes is not one of blood and guts and pea soup, but one in which the world portrayed is simultaneously far removed from yet disturbingly similar to the current one.

Based the Aldous Huxley non-fiction book The Devils of Loudun (which was later turned into a play), the movie is an exploration of how religious persecution is used to mask political machinations. Sister Jeanne, who lusts after Father Grandier, resents his refusal to accept her invitation of becoming the convent’s new confessor. She then accuses him of possessing her through witchcraft. In the meantime, Grandier, who has publicly opposed Cardinal Richelieu, refuses to allow the stronghold of Loudun to be destroyed. These events coalesce into an evil synchronicity that results in mass hysteria, torture, public exorcisms, a sham trial, and Grandier’s eventual execution at the stake.

On a basic level, I grasped the details of the plot, but a half a lifetime later, the standouts remained thus: the rotting face of a Black Plague victim, Sister Jeanne’s hump, and Oliver Reed’s disturbingly sexy portrayal of a priest. Upon my second viewing at the Bloor Cinema this August, I found The Devils even more powerful than before, yet in different ways.

The similarities to today’s social and political climate are nothing less than staggering. Having grown up in the Moral Majority ’80s, I was never oblivious to religion’s stronghold on politics, and vice versa. I realize now that times have not changed all that much since then. Yet as someone who has experienced much more of life in the interim, the stakes are more significant on a personal level.

The Devils, however, does not present these warring factions in black and white (despite the purposefully stark black and white tonal palette of Derek Jarman’s set design).

Vanessa Redgrave imbues Sister Jeanne with no small measure of manipulative hatred and repression, but also the most pathetic strain of spiteful cognitive dissonance; even when she tries to apologize for her mistakes and undo the damage she’s caused she can’t, so she just convinces herself she was right all along.

Father Grandier may be a lusty fellow, but his religious fervor is sincere. His morality may be called into question when he abandons his pregnant mistress, but he truly loves the woman he marries (Madeleine, as played by Gemma Jones).

As Grandier, Oliver Reed is, pardon the pun, spellbinding. There are times in The Devils when not only do you forget you’re watching a film, you forget that there’s anyone else in the cast but Reed. To those who love to denigrate Reed’s ego and recount his alcoholism with distaste, one can scarcely think of any other actors of the time who would have been willing to shave their hair and eyebrows for a role.

The willingness to go off the rails was not limited to Reed. In the 2004 Channel 4 documentary, “Hell on Earth: The Desecration and Resurrection of The Devils,” film historian Mark Kermode presents the film, and by extension Ken Russell himself, as victims of closed minds. Actor Dudley Sutton, who portrays Baron de Laubardemont, is perhaps the most passionate defender of Russell.

“Ken is condemned for so many things and they’re all false,” he says. Read ten online articles, blog posts, or reviews of Ken Russell films and you’ll see that he’s right. It seems that Russell’s films inspire love or hate; rarely is there middle ground. He’s often accused of being outlandish for its own sake, but taking artistic liberties is vital to portraying the subject matter of many of his movies, particularly one like The Devils, whose real-life inspiration was likely far more horrific than we can imagine.

That the film is based in truth makes these incidents even more outlandish. To portray such subject matter with a deadly seriousness would be so overwhelming that any complexities would be lost.

In another chilling similarity to current times, according to the documentary, The Devils was condemned before it was even finished filming, with a host of articles published in the press making exaggerated claims about the goings-on around the set. While it’s likely that the British Board of Film Censors was trying to protect the industry itself from legal action on the grounds of obscenity, it’s upsetting to see that even after nearly 40 years, the film’s most vocal and rapid detractor, film critic Alexander Walker (London Evening Standard), refused to budge an inch. (Mr. Walker passed away in July 2003.)

It’s one thing to stand firm by one’s opinions; it’s another matter entirely to come across like a bitter tyrant, especially when making it all about you. The documentary presents Walker’s story of the infamous TV interview during which he refused to answer Ken Russell’s questions about why his critique of the film detailed two scenes that didn’t even exist. A frustrated Russell hit him on the head with a rolled up copy of the Standard; Walker says viewers called in droves to complain, not that he could have been injured (“it may have contained an iron bar, for all anyone knew,” he quips), but because of Russell’s use of the F-word on television.

All of this controversy tends to obscure the point, which is that The Devils is a true masterpiece of cinema and that it is as relevant now as it was then; its fire has not been dampened, despite the fact that it was heavily censored upon its release and has never been seen in its original form in the US nor received a proper restoration on DVD.

The two major scenes which were cut were the infamous “Rape of Christ” scene, in which the crazed Ursuline nuns of Sister Jeanne’s convent tear down a giant crucifix and have an orgy of simulated sex with it; and one of the final scenes of the movie, in which Sister Jeanne masturbates with the remarkably phallic burned tibia of Grandier. Both of these scenes were thought to be lost for 30 years, until they were found in England during the course of making the documentary.

The documentary presents the former scene in its entirety and it is indeed powerful. As Father Gene Phillips (member of the Legion of Decency at the time and a friend of BBFC head John Trevelyan) remarks however, portraying blasphemy is not in itself blasphemous, particularly when intercut with the sober images of a devout Father Grandier offering communion.

Gemma Jones as Madeleine and

Oliver Reed as Father Grandier

Again, such outlandish images are meant to expose cruelty, hypocrisy, and injustice. Dudley Sutton complains in the documentary that films at the time were “grey” and “shite” and that despite the outrageousness of The Devils (and Russell himself), “underneath it all is humanity.” Russell even points out that “The Rape of Christ” in particular shows how “the nuns have been exploited to the point of total blasphemy of their religion . . . the fact that it is sort of mind-blowing and appalling is what I was trying to get at.”

Russell also countered Alexander Walker’s dislike of the film by insisting, “I don’t make films for critics; I make them for the public.” Although in many ways, the times have not changed, in some ways they have. In the intervening years since The Devils‘ release, we have seen the rise of the “torture porn” genre of horror, and films like The Human Centipede or A Serbian Film.

Father Philips remarks in the documentary that after the initial screening of the uncut version of The Devils, one of the members of the audience told him that although one can “filter” what goes on in Aldous Huxley’s book, “when the filmmaker puts that on the screen, then it’s out there, very much in detail and very vivid.” In other words, you can’t unsee it.

Dudley Sutton as Baron de Laubardemont

This recalls the recent article on A Serbian Film in which Pajiba writer Brian Prisco states that while he doesn’t advocate censorship, “there are scenes no film should ever depict, and this film goes beyond even those.” While I certainly do not agree with the censorship of The Devils (or any film) and I feel strongly that it is a film that needs to be seen, I also think that the choice is with the viewer. The film should be made available for those who decide they want to see it: again and again and again or not at all.

Still, no matter how abhorrent they may appear, sometimes those things you can’t unsee create a new way of looking at the world that is necessary in order for one to continue living in it.

I am most grateful to Rue Morgue and Richard Crouse for conspiring to make The Devils available for viewing on the big screen, and to Ken Russell himself attending and being so delightfully wicked and gracious. You may listen to Mr. Russell’s responses to questions from both Crouse and the audience on YouTube. You may also watch the “Hell on Earth” documentary on YouTube.

To date, The Devils has still not been released in its original uncut format on DVD.

Time limit is exhausted. Please reload the CAPTCHA.